This story was co-published with The Washington Post.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) is being vetted as a possible running mate to join presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden on the 2020 presidential ticket in November. Her raised profile has brought additional scrutiny to her record as a prosecutor — particularly in light of the recent death of an unarmed Black man in Minneapolis that has returned a focus to criminal justice reform in the midst of a pandemic.

In a wide-ranging interview lasting half an hour, the former 2020 Democratic presidential candidate directly addressed her record on issues of race, lessons on inequality she has taken from the pandemic and her commitment to confronting systemic racism in the future. Below is an edited version of the conversation.

19th: I want to start by just asking: How is John [your husband who had coronavirus] doing? Is he much better?

Klobuchar: Yeah, he’s doing much better. He’s now given plasma twice because he has these antibodies, and [doctors] think that’s going to help in the big national push for people that had coronavirus to give plasma.

One of the horrible things about this disease is that it’s hitting certain communities much harder. And that’s our communities of color. You see it with the numbers of people who are dying. You see it with people who are on the front line. People of color are the front-line workers in hospitals in the grocery stores, driving the buses, doing all the work that we now deem and should have always deemed essential.

You can’t divorce the pandemic and the effect that it’s having on communities of color from the overall economic injustices. And my hope is that, if anything comes out of this that’s positive, it’s going to be a really strong case for why we want to invest in housing and better wages and health care and retirement and all these things we need to do so that we have an even playing field.

19th: It sounds like this pandemic has really been illuminating for you as a senator, in terms of the inequality that has really been on display in real time in America over these past few months. What have you learned about inequality in America as a result of the coronavirus pandemic?

Klobuchar: On the presidential campaign, I had been focused on the economic part of the injustice, as well as voting and other things. But I think what really hit me is this is a life-and-death matter.

It is the workforce — which people were actually doing these jobs and why it’s affecting them more than White people. I knew that there were a lot of immigrant workers and people of color in the hospitals, because, you know, anyone that goes to a hospital knows that. But that’s just become so clear that we can talk about this not only as we need to redress the harms and we need to make it better, but also as our heroes.

So I’m hoping this moves the dialogue in a different way. We have immediate stuff which we’ve all been talking about, the protective equipment and unemployment and those things, but how do we reach this into next year so we actually make the policy changes that we’ve been talking about? And one way to do that is to say, “These are the heroes that saved your dad’s life.” And that’s just a different way to talk about it. And that’s something that for me, this pandemic has really crystallized.

19th: I feel like I’ve kind of seen that from you recently. And it really does make me want to ask: There are a lot of White Americans who are on this journey of greater racial understanding about the dynamics in this country. Would you count yourself in that category?

Klobuchar: For me, it’s a way of thinking about it in a much bigger way, and especially our criminal justice system. Believe me, I knew there was racism, or I wouldn’t have worked on eyewitness ID back when I was in the county attorney’s office, or I wouldn’t have done the work with the Innocence Project.

When I first got to the Senate, I actually didn’t ask to be on the Judiciary Committee. They had asked me if I wanted to be on it, and I was like, “I’ve done this for eight years.”

I got myself on there in part to work on these things because of the justice issues and realizing, “You know, I knew there were problems back when I was county attorney, but I can just sit there and say, ‘okay, I’ve done that for eight years,’ or I can be part of the solution.” I think it’s fair to say that in terms of my focus, and realizing you can’t just say there’s a problem; you have to start working to make it better.

19th: I want to shift to, now, exactly what you’re starting to talk about. And that is the pandemic of the relationship with police and Black Americans. You have been in Minneapolis for much of this week. What have you been doing and seeing and hearing on the ground? And based on that, what do you believe needs to happen both in and out of the courtroom now?

Klobuchar: Well, the first was a cry for justice that everyone felt around the country. They watched that gut-wrenching video and literally saw a police officer put his knee on George Floyd’s neck. Almost everyone in America literally saw George Floyd’s life evaporate before them. No ounce of humanity. Cries from the crowd that he couldn’t breathe, cries from George Floyd himself, and [the officer] just kept it up.

And to me, it’s not just one story. It’s a story that so many African Americans have felt — particularly African American men — for so long. The cries for justice were the first thing that we heard, and they were loud and clear.

Then, I got involved. I worked with Attorney General Keith Ellison; we met several times. We met with Reverend [Jesse] Jackson. We kept talking about what we can do in this case, obviously, trying to push the system. Then we got the arrest, and we got the initial charges. I call them initial charges, because I think that there’s more to be done.

And then the second piece of this — what we’ve heard before this case — are cries for change in the criminal justice system, something you heard me talking about on the presidential trail.

Back when I had the job [of county attorney], I was doing things that at the time were groundbreaking. Now, there’s so much bigger stuff that’s groundbreaking, but back when I was there, it was DNA reviews, the work I did to put in a new form of eyewitness identification to reduce racial misidentification, advocating for videotaped interrogations, which was kind of the precursor to body cams. I had done a lot of work with mental health courts and drug courts. We saw 12 percent decrease in our African American prison incarceration rate. We worked significantly with the community. I had community county attorneys assigned to different areas of the city so that they would work with neighborhood groups and with law enforcement to see what the needs were in each community.

Some of the reforms I supported even before all this happened: Number one, taking those police cases, making the elected county attorneys make the decision or an independent process, not the grand jury. Back when I was doing it, nearly every office in the country was using these grand juries. And number two, post-conviction reviews. They’re called conviction integrity units. And Attorney General Ellison and I have been working together to get that done in Minnesota.

Other things would be the Second Step Act. We did the First Step Act, Cory [Booker] and a group of us on [the] Judiciary [Committee], Dick Durbin. But now, the next piece of this is to put incentives for states to do the same thing when 90 percent of people are incarcerated. Another thing would be bail reform.

19th: These are not necessarily things that the broader electorate may be aware of, and in particular, Black voters. I want to talk about this because you are being vetted for vice president. I’m hearing calls from Black women saying that you should not be on the ticket. What is your response to Black women? Coming from somewhere like Minnesota, how do you energize that base of the Democratic Party — or is that not your strength as a potential pick?

Klobuchar: All right, well, first, I am in the middle of not only the pandemic, but of what’s going on in my state. So that explains why, right now, I am not talking about this vice presidential issue. I think Joe Biden was a great vice president. He’s going to make his own decision of who’s on this list, and people are going to advocate for different candidates. I get that. So that is not where I’m going to go with an answer.

But I will talk about my record as a leader in the Senate and as a senator from Minnesota, and that is that I am someone that has focused on economic justice issues and voting rights from the very beginning when I got to the Senate, and I think that’s part of the reason that I’ve gotten very strong support, if you look at the numbers, from the African American community in my state over many elections.

Not everyone agrees with everything you say, I get that. But they know where my heart is. And they know what I’ve done. And that is focusing on economic justice, housing, child care, education, making sure that we increase the minimum wage, retirement savings. I’ve always talked a lot about that.

I have [also] gotten support in our communities from people like Melvin [Carter], the mayor of St. Paul, and Keith Ellison — who, by the way, when I was running for Senate was the first person that gave me a contribution.

One of the reasons that Joe Biden won the primary is because he has a record of support with the African American community, and he has integrity with the African American community. He stood by Barack Obama’s side during that horrendous [economic] downturn [in 2009,] and they made progress, but not the complete progress we need. And so now, this election is a game-change election. I just think that it’s going to matter that he’s leading the ticket, whoever he picks as vice president. I think it’s going to matter that people are sick and tired of Donald Trump in communities of color, with how this pandemic has hit them, when he didn’t do anything to try to change it.

19th: So then, whether you are on the ticket or whether you remain the senator from Minnesota, in terms of what Black Americans are calling for, in these dual pandemics, what would you say that your role is going forward in terms of your commitment to bring about structural change and confront systemic racism in this country?

Klobuchar: Well, I think it has to happen now. I’m well aware of the political barriers with Trump in. But I’m a member of the Judiciary Committee. I think we have to have immediate hearings about criminal justice reform. Because right now, it’s not just the African American community. It’s all of America that’s horrified by what they saw on the video. We need to move on this now. To be able to basically make sure that the legacy of George Floyd is not just charges and the justice we need to see out of the criminal case here in Minnesota, but it’s also bigger criminal justice reforms. I pledge to do that immediately, as a member of the Judiciary Committee.

The second thing is economic justice, which honestly, we’re going to need a new president to do. And that means putting in place structural changes. It’s going to be investment in the communities, yes. But it’s also going to be education and child care. And that while we keep our eye on the immediate, which is the criminal justice reform, that we look at the underlying structural problems that led us to where we are.

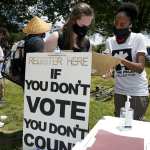

And then the third thing would be voting. And that’s something that I am leading on and have the obligation to get done. That’s getting the money in the next pivot package, to make sure that people have the funding so that they can get their mail-in ballots and they can get the envelopes and everything they need, so that they can vote safely and not have to choose between their life and voting.

19th: Do you see yourself as the type of person who could bring along White Americans who, like you said, need to have a better understanding that these are issues that impact all Americans. Do you see that as your role now?

Klobuchar: I do. And I think I have a unique position to be able to do that. I’ve always gotten support with our base in my state, but I’ve also been able to bring in people in the suburban, exurban areas, as well as rural. And I think if we really want to break down this divide and do some big things when it comes to voting rights and criminal justice and economic justice, we know we need to bring friends. African American women have been holding this up for too long; they need some help. They need others to take up the cause as well when it comes to supporting candidates and getting things done. And that’s something that I uniquely bring in my elections and in the way I’m able to talk about issues and bring in other people into our party and into the cause. And that’s what I pledge to do as a senator.

Recommended for you

From the Collection