This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

Kayla Reed watched with surprise as the primary election returns in Missouri rolled in late Tuesday: 10-term congressman William Lacy Clay, who was part of a Black political dynasty in the state, had just been dethroned by Cori Bush, a Black pastor and nurse whose path to victory began on the streets of Ferguson in 2014.

Reed, 30, was also a protester then, proclaiming that Black lives mattered long before the country would accept those words as mainstream. With Bush’s Democratic primary win in Missouri’s 1st District, a leader of the Black Lives Matter movement is likely headed to the halls of Congress for the first time.

“I think I was shocked for two minutes, and then I realized the implications of her victory,” Reed said. “I thought about what this meant for the movement. Right now, it’s popular to say, ‘Black lives matter.’ It’s popular to call for defunding the police. Six years ago, we were in a completely different place politically. Many of us had no idea what Ferguson was going to give way to. This is something where people can see how much moments like Ferguson can change an entire political landscape. The work of the movement put Cori over the top.”

Bush will face Republican Anthony Rogers in November. If elected, she will be the first Black woman to represent Missouri in Congress. The district is safely liberal, with Clay beating his Republican challenger by 63 percentage points in 2018.

Bush’s victory is the latest and biggest for the Black Lives Matter movement, which has evolved since the police killed unarmed Black teenager Michael Brown in 2014, breaking open the frustration of generational oppression in Ferguson that centered on racial disparities in policing but also the systemic racism in the region’s governing structure.

The win also takes on added meaning in the wake of the death of Rep. John Lewis, who was a young activist who went on to use politics to fight inequality, Reed said.

“I think about what it must’ve been like to see him go to Congress after the Civil Rights Movement,” Reed said, borrowing a phrase from Lewis and adding, “I think Cori will stand in the legacy of ‘good trouble.’”

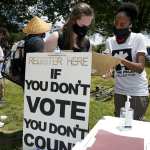

In the past six years, the Black Lives Matter movement has increasingly translated protest into politics and policy. Activists have been elected as prosecutors and mayors across the country, and perhaps nowhere has that transformation been more on display than Missouri.

A year after Ferguson, attorney Wesley Bell was elected to city council. In 2016, Kim Gardner became St. Louis’ first Black circuit attorney. St. Louis Treasurer Tishaura Jones came within 888 votes of becoming mayor in 2017 and is considering another run in 2021.

In 2018, Bell defeated Bob McCulloch — the prosecutor who declined to indict former Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson in Brown’s shooting — to become St. Louis County’s first Black prosecutor. And this year, Ella Jones was elected Ferguson’s first Black mayor.

The gains have not been episodic, but the result of consistent disciplined organizing, said Brittany Packnett Cunningham, whose activism was also born in Ferguson.

“America would not be ready for this moment of revolution if Ferguson and other cities had not helped remind all of us of our responsibility to democracy and each other,” Packnett Cunningham said. “If people think the story stopped in Ferguson in 2014, they have not been paying attention. It teaches all of us how to resist and how to win.”

In Chicago, activists helped to elect Kim Foxx in 2016, ousting Anita Alvarez, who drew fire for her handling of the Laquan McDonald shooting and subsequent cover-up of his case by city officials. The city’s former mayor Rahm Emanuel, whose tenure was also marked by the McDonald case, declined to seek a third term in 2018 — seen as a victory by activists. In Philadelphia, former defense attorney Larry Krasner, who represented Black Lives Matter protesters and ran on a platform of criminal justice reform, was elected district attorney in 2017.

“There’s always been an understanding that our pathway to power required us getting creative about our vision and our demands,” said Chicago activist Charlene Carruthers. “Bush’s victory is connected to people understanding that the results we need have to happen on multiple terrains.”

It is also encouraging for many of the Black women who have fought for such gains from the margins to see their policies and candidates being validated at the ballot box. For years, they were working from the idea that their ideas would always be dismissed, said progressive political strategist Camonghne Felix.

“I can’t even begin to imagine what the next decade of American politics is going to look like, because it’s so disruptive,” said Felix. “I have to think completely differently about what might be possible. For the people of the movement, this is not just a seat at the table — they’re building a whole new table. We have power. It’s ours now.”

Reed, co-founder of Action St. Louis, a grassroots organization focused on electing down ballot candidates, said the moment represents “kind of a harvest of the seeds we planted six years ago for those of us who have been tilling the soil.”

“To unseat that level of entrenched political influence and power, it changes everything,” Reed said. “Ferguson wasn’t this pop-up moment that just fizzled out; there was a legacy of folks that were so forever changed that they have continued the work. We have not taken our foot off the gas.”

Recommended for you

From the Collection