Paula Greisen might not have fought a case before the Supreme Court had Ruth Bader Ginsburg not done it nearly half a century earlier.

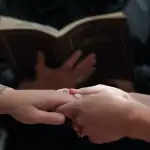

It wasn’t that Ginsburg had laid pathways for women aiming to go into law, though she certainly did. It was December 2017, and Greisen was a lead attorney on Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, the famous Supreme Court case involving a Colorado baker who had religious objections to gay marriage and two men in search of a wedding cake. In a 7-2 decision, the court threw out a lower court’s ruling against the baker, finding it hostile to his religious beliefs.

Much of Greisen’s work fighting for LGBTQ+ rights has drawn on legal precedent set by Ginsburg, who dissented in the case.

“She was the architect that laid the foundation for current modern thinking about equality in our country,” Greisen said.

Ginsburg, who died Friday, created case law banning sex discrimination that set the stage for LGBTQ+ legal wins decades later. In the 1970s, Ginsburg took a spate of sex discrimination cases to the Supreme Court, arguing that the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution barred discrimination due to gender. Her winning arguments cemented sex discrimination protections into Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Shannon Minter, legal director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, said the world be profoundly different for LGBTQ+ people without her.

“Without the early sex discrimination cases that she brought, starting in the early 1970s, and without her very strategic broad vision of how to persuade the court to recognize a very expansive understanding of sex discrimination, we would be living in a very different world,” Minter said. “There would almost certainly be no sex discrimination protections for LGBTQ people.”

Minter called Ginsburg’s work the “doctrinal foundation for the marriage equality ruling for same sex couples.”

Since Ginsburg’s appointment to the court in 1993, she ruled on the most important cases impacting LGBTQ+ people. She was part of the majority that struck down sodomy laws in Lawrence v. Texas in 2003. She helped overturn the Defense of Marriage Act, prohibiting same-sex marriage in 2013. In 2015, she joined the court in bringing marriage equality to every state via the Obergefell v. Hodges ruling.

Looking back now, Minter is struck that one of Ginsburg’s last rulings on the court was the Bostock v. Clayton County case, which cemented LGBTQ+ workplace protections nationwide.

“Her vision of sex discrimination law, and the broad way it should be interpreted to prohibit any type of sex-based disparate treatment, really the culmination of that vision was the Bostock decision,” Minter said.

Although Ginsburg is often praised as a progressive voice on the court, legal experts say that much of her legacy is as an attorney who interpreted the law broadly. She viewed sex discrimination as a threat not to just to women, but to men.

In bringing discrimination cases on behalf of a male caregiver denied a tax deduction for female caregivers, she began building case law that would later be used to protect people of all genders, including transgender and nonbinary people.

“She was able to show the court how discrimination against [the caregiver] can hurt us all, and by using the 14th Amendment in such a way, she was able to essentially pave the path and lay the foundation for our present-day understanding that any type of inequality, any type of discrimination is harmful to the country as a whole,” Greisen said.

Jenny Pizer, law and policy director for Lambda Legal, recalls that in the 1990s, legal rights advocates hadn’t started using sex discrimination protections to fight LGBTQ+ cases.

“There was a point where we wanted to very significantly expand the scope of the domestic partner laws,” Pizer said. “And it was very clear to me that a key element of our argument had to be that it was rights and responsibilities.”

Then, they hit a pivot point. Reframe the argument as sex discrimination, just like Ginsburg had done years earlier.

“Let’s use it as an opportunity to get at stereotypes, which was of course a key thing, and she was the most effective person during those years showing the harm of many directions of gender based assumptions and stereotypes,” Pizer said. “That approach has been just immeasurably huge in our work.”

Chase Strangio, an attorney with the ACLU who represented Aimee Stephens in her landmark Supreme Court case on transgender rights, said it’s important to remember that Ginsburg was also the product of people around her, people who pushed her, challenged her and taught her.

“I want to serve credit both to her as an individual and an exceptional individual, and also the people she came in contact with and learned from that enabled her work to be what it was,” he said.

He noted that attorneys Dorothy Kenyon and Pauli Murray fought sex discrimination cases in the 1940s and 1950s, work that Ginsburg would later credit.

“Our institutions have to be bigger, and our movements have to be bigger than any single person,” Strangio said. “It’s incumbent upon us to ensure that they are, and so, that’s the work moving forward.”