A gynecologist performed hysterectomies on detained migrants without their full consent, according to a nurse who filed a whistleblower complaint with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General on Monday.

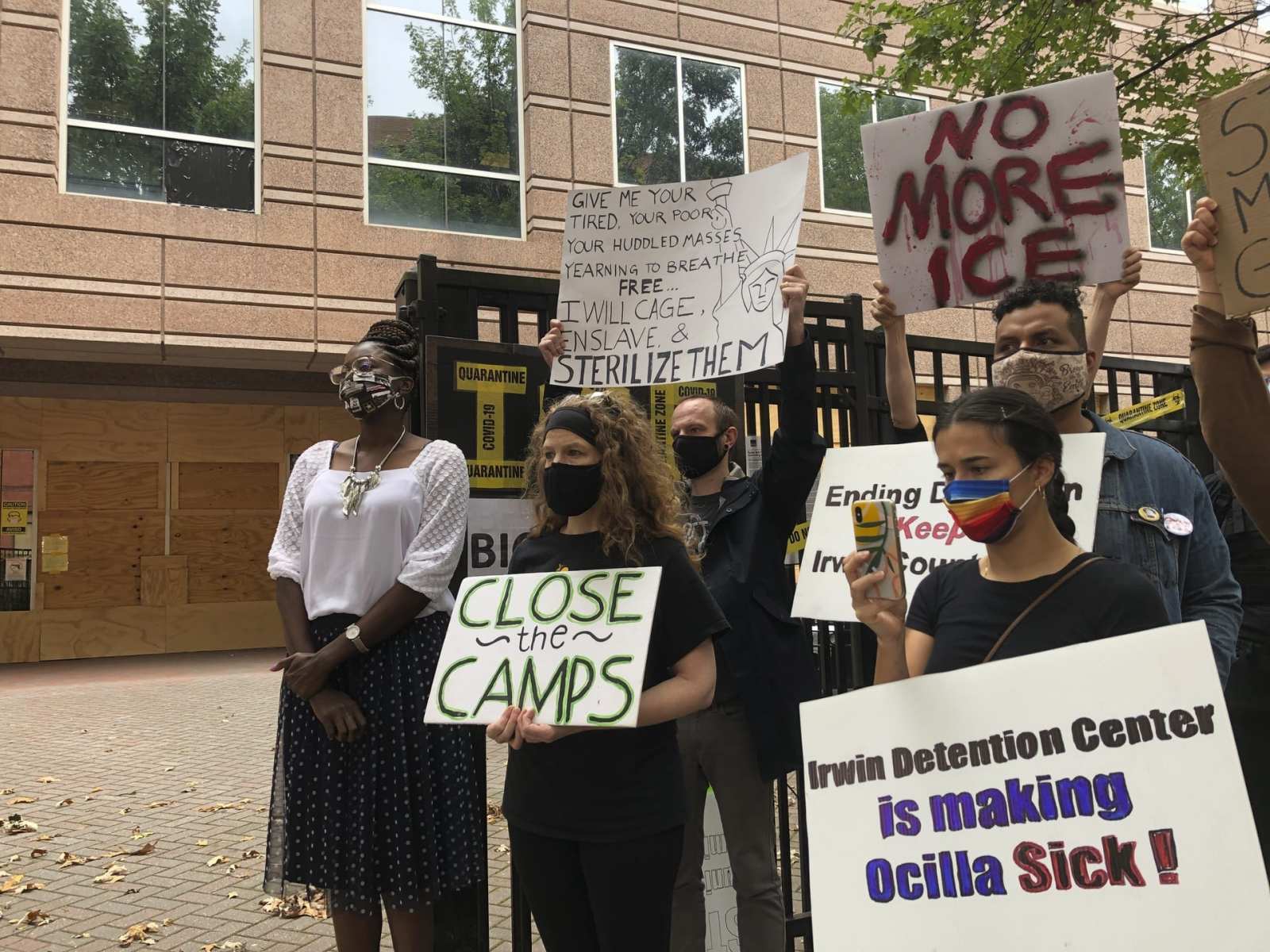

The nurse, Dawn Wooten, who worked at the Irwin County Detention Center in Ocilla, Georgia, said in her complaint that the number of hysterectomies — invasive operations that remove all or part of the uterus — was a red flag. Almost every woman that went to see the doctor was told they needed to undergo the procedure, she claimed.

“Everybody’s uterus cannot be that bad,” Wooten said in the complaint, calling the doctor “the uterus collector.”

Wooten also claimed that the women, who spoke predominantly Spanish, “expressed to her that they didn’t fully understand why they had to get a hysterectomy.” Some nurses communicated with medical staff by using a simple Google search as a translator, the complaint alleges.

“When I met all these women who had had surgeries, I thought this was like an experimental concentration camp,” an anonymous detainee said, according to the complaint. “It was like they’re experimenting with our bodies.”

ICE does not comment on matters presented to the Office of the Inspector General, according to Lindsay Williams, a spokeswoman. The federal agency spends more than $260 million each year for detainee healthcare services, and the Irwin County Detention Center — a facility operated by private prison company LaSalle Corrections that houses nearly 5,000 detainees — repeatedly operates in compliance with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s standards, she said.

“In general, anonymous, unproven allegations, made without any fact-checkable specifics, should be treated with the appropriate skepticism they deserve,” Williams said in a statement.

Elspeth Wilson, an assistant professor of government at Franklin and Marshall College and author of “The Reproduction of Citizenship,” said these allegations against the ICE facility in Georgia are a continuation of the country’s “eugenics movement” that dates back to the early 1900s.

In 1905, Indiana became the first state to approve a sterilization law “making sterilization mandatory for certain individuals in state custody,” and to prohibit marriage licenses for “imbeciles, epileptics and those of unsound minds” in an effort to reduce reproduction. During the next several decades, more than two-thirds of all states passed similar laws, legislation that affected many poor women, especially those associated with poverty, disability, criminality, alcoholism or even having children out of wedlock, Wilson said.

In the 1927’s Buck v. Bell, the U.S. Supreme Court decided to uphold a state’s right to forcibly sterilize a person considered “feeble-minded.” At the time, Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes defended the involuntary sterilization of 17-year-old Carrie Buck — who was committed to the same asylum as her mother after giving birth to an illegitimate daughter — by saying “three generations of imbeciles are enough.” The superintendent of the Virginia Colony testified at the time that members of Buck’s family belonged to the “shiftless, ignorant and worthless class of antisocial whites of the South.”

As a result of the case — which has never been overturned — as many as 70,000 Americans were forcibly sterilized during the 20th century.

“England and the United States started the eugenics movement, not Nazi Germany,” Wilson said. “After World War II and the Holocaust, the United States doesn’t even acknowledge our eugenics past.”

The idea, Wilson said, was that America would be stronger if only the physically and financially strong reproduced. Eugenics was popular among political leaders and policymakers in the 1920s and taught at reputable colleges and universities across the country.

The Great Depression dampened the eugenics movement as more people began to suffer financially, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a disabled man in a position of power, changed public perception.

During the Civil Rights movement, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration allocated federal funding to family planning as part of his “unconditional war on poverty,” which then primarily targeted public institutions within communities of color. The justification for sterilization shifted from “defective genes” to family size and dependency. Some eugenicists claimed that poor and minority people were “hyperbreeders” draining public resources from White people.

Sterilizations increased in the South around the same time that African Americans gained access to federal programs, including Medicare and Medicaid, after the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964. Black communities were disproportionately subjected to forced sterilization.

In 1973, the Southern Poverty Law Center filed a case after Minnie Lee and Mary Alice Relf, two Black sisters in Montgomery, Alabama, ages 12 and 14, were coerced into federally funded sterilization. Their mother, who could not read or write, signed a consent form with an “X,” but thought she was approving birth control shots — not surgical sterilization. The case was highly publicized and the public was outraged, Wilson said.

Jamille Fields Allsbrook, the director of Women’s Health and Rights at the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank, reiterated the United States’ historical precedent.

“The United States has a long and sordid history of reproductive coercion and forced sterilization, particularly targeting Black, Latina and Native American women as well as women disabilities and incarcerated women,” Allsbrook said in a statement. “These racist, eugenicist practices are often sanctioned by U.S. law, which to this day allows for the sterilization of anyone deemed ‘unfit.’”

In California, Mexicans and Latinas in prisons, mental institutions and the welfare system were disproportionately sterilized between 1920 and 1945. Native Americans and Puerto Ricans who relied on the federal government for health care were also targeted.

According to some reports, at least one quarter of Native American women between ages 15 and 44 between 1973 and 1976 were sterilized. And about one-third of all Puerto Rican women of childbearing age were sterilized between the 1930s and 1970s, Wilson said. Many people were sterilized after giving birth without even knowing it.

“I honestly think it was doctors who thought poor women of color were having too many children,” Wilson said. “It sounds very racist to me. If you leave things to health officials and institutions, certain individuals can really abuse their power.”

Correction: This article originally included phrasing that implied Puerto Rico is no longer an American territory.