Twenty years ago, Kelli Dillon started to feel abdominal pain. Dillon, who was 24 at the time, was serving a sentence at Central California Women’s Facility, the largest women’s prison in the world, for shooting and killing her husband while defending herself against domestic abuse. The prison gynecologist told Dillon she had an abnormal pap smear and needed a biopsy to look for cancer. Then he asked if Dillon wanted more children. And she did. She had been separated from her two boys — in her 15 years at CCWF, she would only see them five times — and she dreamed of being able to raise a family hands on when she was free.

The doctor created a plan with Dillon: If he found cancer, he would do a hysterectomy.

In 2001, Dillon and four other women were put in chains to go out for surgery. “Everything is an assembly line,” she said. Nurses rushed her through the paperwork, and soon she was under anesthesia. When she came to, she immediately felt uneasy.

“When I came out, I felt like something was wrong,” she said. “He told me everything is fine, we took out some cysts.”

Dillon asked the doctor if she would still be able to have children. “Yeah, I don’t see why not,” she remembers him saying.

For almost a year after the surgery, Dillon didn’t menstruate. She had panic attacks, lost 100 pounds and sweated at night — all symptoms of surgical menopause. Dillon sent a letter to Cynthia Chandler, co-founder of Justice Now, a nonprofit in California focused on abolition and providing legal assistance to people in women’s prisons. With Chandler’s urging, Dillon requested her medical records.

Dillon never had cancer, and yet her ovaries and part of her fallopian tubes had been removed. She didn’t find out until Chandler went through her medical records with her during a legal visit in prison.

“I had been intentionally sterilized, and I have been lied to,” Dillon said.

Dillon’s experience is the focus of a new PBS documentary “Belly of the Beast,” debuting in an online release October 16. While incarcerated, Dillon connected other prisoners who’d been sterilized with Justice Now, and their voices are featured in the film. These procedures happened so frequently that some referred to them as the “surgery of the month.”

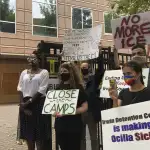

Now 44, Dillon says it feels “ordained” that this film will release not long after a whistleblower alleged that a gynecologist performed hysterectomies on detained migrants without their full consent at a Georgia immigration detention center.

In 2013, the Center for Investigative Reporting revealed a pervasive culture of forced sterilizations throughout women’s prisons in California that have remnants of the eugenics movement. Prisoners in California reported being asked to consent to these surgeries while under anesthesia for other medical procedures, including C-sections. The OB-GYN at Valley State Prison, James Heinrich, told CIR that the $147,460 the state paid for sterilization procedures from 1997 to 2010 was minimal “compared to what you save in welfare paying for these unwanted children – as they procreated more.”

The flood of media attention following this investigation led to a state audit and legislation that would criminalize this procedure in state prisons. Dillon, now out of prison, testified before California state legislators when it seemed like legislation had stalled.

“I wanted a second chance at life, I wanted a second chance at being a mother,” Dillon told lawmakers in 2014. “I trusted this surgeon to respect and to acknowledge that I still had a future and that I wanted one. I feel like I’ve been robbed of the fullness that could have been given to me had this not happened to me. Did this happen because I was African American? Did it happen to me because I was a woman? Did it happen to me because I was an inmate? Or did it happen to me because I was all three?”

That same year, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill ending forced prison sterilizations, but, as the film shows, that didn’t necessarily change attitudes on the inside.

“As to whether I think it should be illegal, not necessarily,” a former correctional nurse, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said in the film. “Even if it’s not medically necessary, it could or would in the long run save the state funds … The ideal time to do it to them is when you’re already in there. It just takes a couple more minutes, a couple more snips.”

As of last year, Dillon and Justice Now began work on legislation that would provide redress for those involuntarily sterilized in California. “Belly of the Beast” encapsulates more than a decade of efforts to hold California prisons accountable for these abuses. In conversation with The 19th, Dillon and the film’s director and producer, Erika Cohn, discuss the pandemic, the eugenics movement and the alleged hysterectomies in a Georgia ICE detention center.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The 19th: Kelli, you said in the film when you were thinking about testifying in front of the legislature in California, that this is your story, something that you own and decide who you tell it to. Because each time you divulge and relive this trauma, you’re the one that has to go home and deal with it. So what was the process of you deciding to re-live everything in the documentary world?

Kelli Dillon: Erica did a phenomenal job in capturing those actual moments for me, especially when I was in the courtroom and different things like that, the reenactments, because it was so accurate from her telling. She did a great job.

But also, it was hard. I’m very bold about a lot of things that I talk about, I have a very strong voice in a lot of different areas. But this is the only area that really brought me pain, shame. I felt that I was going to be judged, because I have been judged in so many different areas of my life, and there was no compassion or consideration for the trauma that I have been through. So it took me a moment to really just get the courage to share that story. But it was in Erica’s kindness, her understanding of eugenics and understanding of the history of sterilization, the U.S. history of sterilization is what actually gave me the feeling of trust — to trust her with my story. And still, even though we were filming in the backdrop of my life, I still hadn’t really came out publicly and very strongly or boldly about my story until “Belly of the Beast” started to be featured.

I think right now people are talking a little bit more about eugenics and sterilization because of what’s happening with the whistleblower complaint out of the ICE detention center in Georgia. Even with that story, I think the reaction was ‘This is something that has never happened in this country,’ let alone something that happened, and is well documented, in California prisons too. Can we talk a little bit about the history?

Dillon: While we were trying to pick up momentum for “Belly of the Beast,” that’s when Dawn Wooten also came out [with the whistleblower report alleging hysterectomies in an ICE detention center in Georgia]. What was happening, was such an ordained time. The fact that we were saying these things were happening and are happening in the state of California, and to have it confirmed and verified on the other side of the United States in the exact same way, almost verbatim, was like, “Whoa.” It made everybody have to take action, and pay attention to the fact that no, there is no denying, this is not a conspiracy theory. This is actually happening to women of color in this modern day.

When I heard it, I was like, ‘Oh, my God, like, that’s my story.’ It really was a wake up call and it strengthened me, and gave me more courage. Because I was a little worried about me being alone over here in California, and stating that it’s not just a California thing, but a United States thing. But to see Dawn Wooten come out and speak so boldly and courageously as a staff member … I didn’t feel alone anymore.

Cohn: That was a conversation that Kelli and I had a lot making the film: How do we make it abundantly clear that this is not just California, this is not just Kelli? This is eugenics as an ideology. Forced sterilization is genocide, and has a legacy in the United States, and that’s deeply rooted in white supremacy.

When we think about eugenics today, we are witnessing systemic racism and population control — through policing, through imprisonment, through the immigration detention system and lack of access to health care. This is just another instance of modern day eugenics.

At the end of the film, we chose to focus on California … But, we calculated and did a lot of investigative reporting work on our own and found that between 1997 and 2013, 1,400 sterilizations were performed [in California prisons]. Our team sent Freedom of Information Act requests to states all over the country. And we know that at least eight other states allow sterilizations under certain circumstances, and a lot of states chose not to respond to our request. So we know that it’s happening, but we don’t know to what degree. And given the levels of secrecy and privacy these institutions hide behind, it’s incredibly difficult to uncover these abuses of power. And so, as Kelli mentioned, it’s really essential to us to draw those parallels historically and present day, so that people are forced to confront our history and our history of genocide.

When so many people think of eugenics, they think of Nazi Germany, they think of the Holocaust. Yet many of us don’t actually know that the eugenics movement was founded here in the United States, and Nazi Germany leaders actually came to the United States, came to California, to learn about our eugenics policies, forced sterilization being one of them. So that that history was really, really important.

There was a nurse whose face is blacked out, who essentially says she doesn’t know whether sterilizations in prison should be illegal or not because it saves the state money. And Dr. Heinrich [the OB-GYN at Valley State Prison] said [to the Center for Investigative Reporting] the forced hysterectomies are cheaper than welfare. What is your response to people upholding this system?

Cohn: It took a long time to find people who would be comfortable speaking about what happened. A lot of nurses and other health care providers were very concerned about retaliation. The nurse interviews actually came at the very end of our filmmaking process, and we completely restructured the film around that. It was essential for that to be included because it’s not just about one doctor, it’s not just about Dr. Heinrich, it’s about the entire system. And it really shows how pervasive these practices can be and how difficult it is to uncover these abuses of state-sponsored violence, because the threat of retaliation is so real from the staff to the people who are incarcerated.

Dillon: I’m going to take it back to the welfare comment. They want to hide behind the fact that African American women or children that are poor, or formerly incarcerated people, are a burden on the system, when we know that we are not even 10 percent of the population in the whole state of California. There’s this constant layer of cover-ups, of putting these stigmas on a certain population. That is one of the things that has happened to the African American Black woman: We’re seen as welfare recipients. And we’re seen as burdens on the system. If you can perpetuate that lie, and perpetuate those issues, then it’s easier to get not only the buy in for the agenda and the policy to sterilize us, but you can also get the person who thinks they have a moral high standard of preserving life … you can get them to buy into that bullshit too.

Both of you have talked about how hard it was to get the nurses to talk because of fear of retaliation. It’s the same for people who are either currently or formerly incarcerated. But what about your own sentiments? Have you felt any tangible threats of retaliation? Are you concerned about it?

Cohn: I was primarily concerned throughout this process about how people inside would experience retaliation, and that was a very real and raw conversation that we had in the process of making the film. And one of the reasons that it’s so difficult to have any legal redress for sterilization survivors is the statute of limitations, as you see in Kelli’s case. And also, literally, you have to file a complaint against the person who committed the harm against you to be eligible for litigation. And so a lot of people inside actually don’t do that out of fear of retaliation.

Kelli working on the inside is kind of an advocate for so many other people, as you see in the film, you know, encouraging people and coaching them through the process of how to file complaints and and to be a support system for people inside to that process was pretty incredible. Do I have fear about retaliation against me personally? No. My concern has been primarily for the people who have the courage to share their direct lived experiences.

Dillon: I didn’t have fear of retaliation while in there; I was too pissed off. At the time, I was angry. I was ready to fight everybody. I was pissed off number one for being there for protecting myself from my abuser. Then I found out that these motherfuckers took my ability to even be a mother again.

I can’t even tell you how many times I was written up. I fought, I was angry because I couldn’t explode the way I wanted to, so I imploded and I began to break down internally and go through massive depressions and panic attacks. I had a faceless predator. It wasn’t just one person — it was the whole fucking system.

So by this time, I was ready to go up against whoever. I was intimidated on how to do that because of my lack of education, because of my status — I was poor. But at the same time, was I willing to do it? Hell yes, I was willing to do it.

What you just said in describing a faceless enemy reminds me of the rhetoric around COVID-19 being this invisible killer. Watching this film during the pandemic, particularly the part where, Kelli, you’re cleaning the sink and talking about being a germaphobe and picking up extreme cleaning habits in prison, I wondered about how you’re doing right now.

Dillon: In the first three weeks of COVID, when they finally started doing the stay-at-home orders and we started looking at the bodies dropping, immediately I went into a place of anxiety of being incarcerated. Number one, in terms of being locked down — like, that took me back. Number two, the things we had to do, being separated from society, it just was a trigger. And I spoke to a lot of my sisters that were formerly incarcerated, they were also triggered.

Then on top of that, as an incarcerated person, we’re not given all of the information; they just tell us when things are locked down, and then let us know when we can come out. And we’re like, what’s happening? So immediately we went into a place of not trusting the government, feeling that they were trying to harm us and not tell us what was going on. I had a couple of panic attacks, anxiety attacks, in which I had to calm myself down and say, “I survived that, I can survive this. This too shall pass.”

In the film, Kelli, you wonder when your happy ending is coming. How are you doing with that?

Dillon: That happy ending has been a journey in itself as well. I have allowed it to evolve. I had an idea of what my happy ending would be after prison. And when I came home, I found that it was something different, and there were some more challenges. I had a happy ending with my children, and they were processing their own feelings of me being away and the trauma that they have been through, and so that changed. I think it comes with being a middle aged woman.

But I always tell Erika, I live in LA, and living so close to Hollywood can fuck you up in the mind where you feel like you’re supposed to have a happy ending, right? We’re making this movie, we’ve got to have a triumphant moment at the end. I was waiting on that moment to happen. But now, I am embracing happiness each day. I am embracing my feelings of peace, of safety, of contentment, and the fact that that is making me have a smile on my face. That it’s giving me the continuation of hope. Instead of wanting a picture of what that happiness is supposed to look like, I’m actually looking forward to the surprise of what it’s going to be.