We’re the only newsroom dedicated to writing about gender, politics and policy. Subscribe to our newsletter today.

As the pandemic rages and voter enthusiasm is at a record high, Americans are being urged to make a plan to cast their ballot in the most consequential election many of us will ever live through.

My plan was to vote early, something I did frequently in my native Georgia before moving to Philadelphia five years ago. Because of the pandemic, Pennsylvania allowed voting before Election Day for the first time this year.

I requested my mail-in ballot, but was among the untold number of people who never received it — which is how I found myself headed to a precinct in the most populous county in the state, on the day before the end of early voting, to cast my ballot in person.

I chose the Liacouras Center at Temple University, not far from my apartment, guessing the line would be shorter than at, say, city hall, a popular voting location.

I have been voting for more than two decades. I have rarely missed an election, and have voted in every presidential election since 2000. It has never taken me more than 20 minutes to cast my ballot.

On Monday, I emerged exhausted, demoralized and enraged after four hours of standing in line.

How, in the city where the Constitution was written and signed, where we celebrate the founding principles of democracy, is this happening? I was angry not for myself, but on behalf of the Philadelphians who could be disenfranchised this election. I am someone who had four hours to stand in line; there are too many who live in this city who do not.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

I work for a newsroom named for the 19th Amendment. Our logo includes an asterisk, a conscious recognition of the Black women who also fought for the right to vote, but who were blocked from the ballot by White women who sacrificed them for their access to the franchise. It was with these dual realities in mind that I especially looked forward to voting this year, the centennial year of suffrage, 55 years after the Voting Rights Act. I headed to the polls with Ida B. Wells and Fannie Lou Hamer — both suffragists and founding mothers of our country — on my mind and in my heart.

I was excited and emotional at the thought of bringing my race and gender into the ballot box with me. The moment was supposed to be a bright spot in an otherwise chaotic and uncertain year. Instead, it would leave me feeling that chaos and uncertainty more acutely than ever.

In recent weeks, I have tweeted and talked on air about the long lines and record turnout seen in states from Texas to Georgia to Wisconsin to Florida, pointing out that voter excitement is also a signal of voter suppression. There is and has been a voting access crisis in this country, and like the other pandemic, it is one thing to cover these issues, but another altogether to experience them.

My understanding of this issue was deepened in the four hours I inched toward the ballot box. I say this not because I consider myself a victim, but because I now feel empowered as a witness.

The first hour was merely an irritation, the cost of maybe not squaring away my own voter registration information so that my ballot would arrive and I could conveniently drop it off at a designated polling location. I filled out a form from a volunteer and waited patiently for my turn.

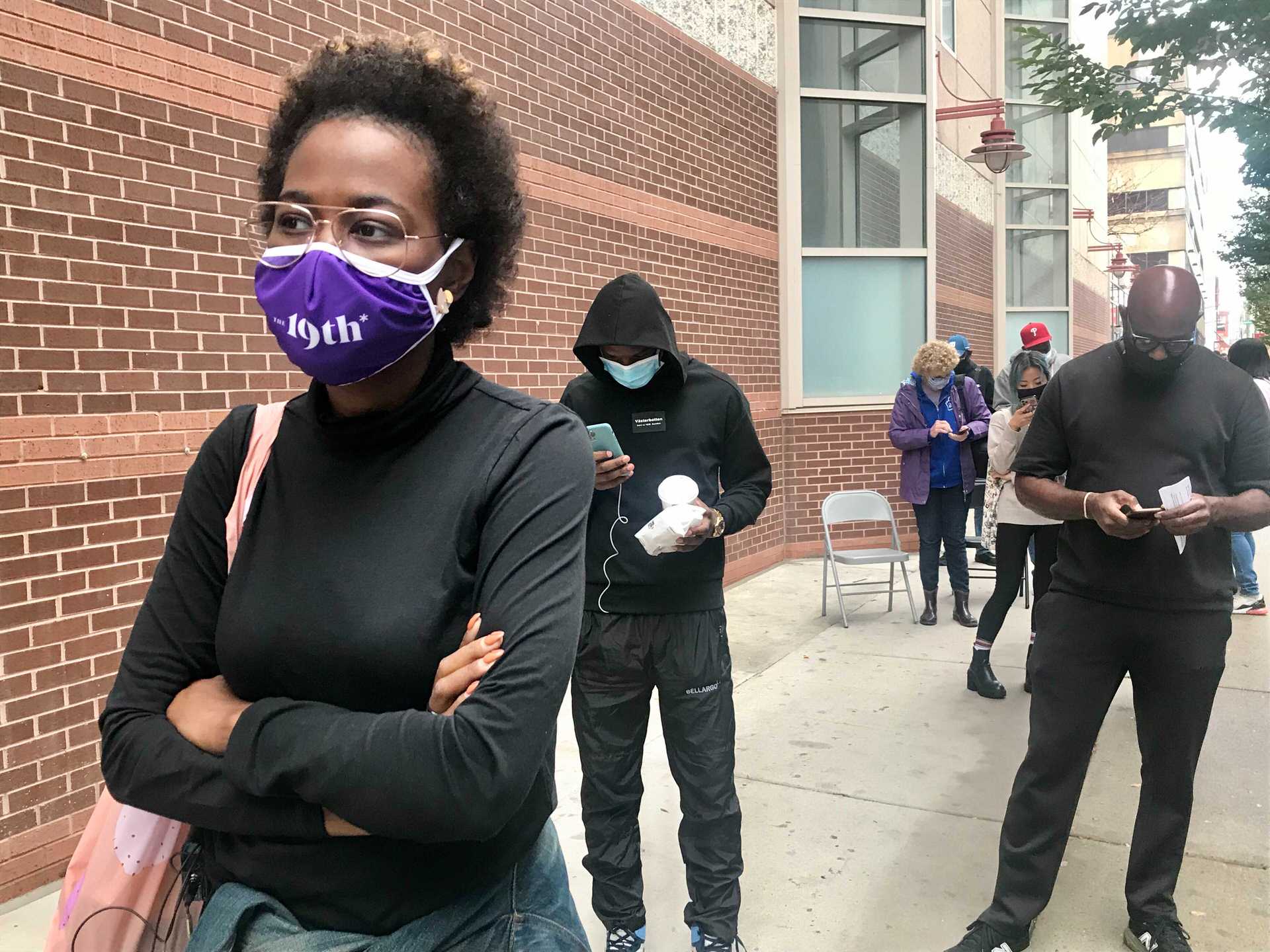

By hour two, I had barely moved half a block. I noticed that many of those standing in line with me were African Americans (Black people make up the plurality of Philadelphia residents), but the crowd was diverse in gender and age. Most were masked, but hardly any were socially distanced.

Along the way, the older or less healthy were given folding chairs — never a good sign at the polls, but rather an unspoken agreement to prepare for the long haul. By the near end of my long wait, I’ll admit that I was among those that took a seat when it was offered.

As I neared the entrance, I noticed a DJ playing music and a pair of drummers. The entertainment was meant to be a distraction from the debacle. A volunteer passed out snacks, and I remembered that I hadn’t eaten lunch — I’d planned to go after I voted, and I’d arrived at the precinct shortly after one in the afternoon.

When I did finally make it from down the block and around the corner to the front of the line, at nearly 5 p.m., I was alarmed to see only three poll workers seated behind plexiglass. They were all Black women, which has been my experience so many times that I have cast my ballot.

I sat down with the third poll worker as she looked up my information.

“Are you registered to vote, Miss Haines?” she asked me.

“Absolutely,” I said, panic rising in my chest.

The next words she said have no doubt caused dread in an untold number of my ancestors and Black people who have attempted to vote in the past several weeks.

“I have no record of you being registered,” she said.

The thought of not being able to cast my ballot nearly brought me to tears.

But my fate was temporary; she had only spelled my name incorrectly. A few moments later, she was handing me my ballot and pointing me to my private booth for me to select my choices.

Picking my candidates and weighing in on the city’s ballot initiatives may have been the few minutes I’d felt good the entire afternoon. And even then, I was nervous about whether I was doing anything — using the wrong pen ink color, putting the envelopes together in the incorrect order or my signature in the wrong place — that would disqualify my vote.

I thanked everyone for their help throughout the process; I know the dysfunction is not their fault. Like us, they also needed help. Unlike us, they’re not likely to get any.

I thought of the woman astronaut who cast her ballot from space — from space! — this week more quickly than I just had.

I submitted my ballot and peeled off my “I Voted Today” sticker, usually a point of pride. Out of habit, I stopped outside of the precinct, still in my mask, to pose for a sticker selfie. But on the inside, I didn’t feel proud.

I wondered how many people passed by, saw the line, and kept walking or driving.

I think most of the people in line with me stayed, as far as I noticed. But standing there, I wondered how many people passed by, saw the line, and kept walking or driving. Who said they’d maybe come back later, or who never returned at all? Who went to another location and were maybe able to vote, but maybe not?

For the first time, that sticker didn’t make me feel like part of our democracy; it felt more like I had won a cruel lottery. Because of my experience, I now know that no matter who wins this election, too many of my fellow citizens are still losing.