Kellie Nemke knows too well what it’s like to not be able to go home for the holidays.

Twenty years ago, she came out to her family, which she recalled “didn’t go exceptionally well, initially.” She had just moved to Eugene, Oregon, and didn’t want to trek back to the Midwest to spend Thanksgiving with people who weren’t necessarily thrilled to see her.

Eugene had a vibrant queer scene, and many in her community weren’t welcome at their family dinner tables or would have to hide who they were if they went home. So Nemke did what a lot of LGBTQ+ people have done for generations: She organized a holiday gathering with chosen family.

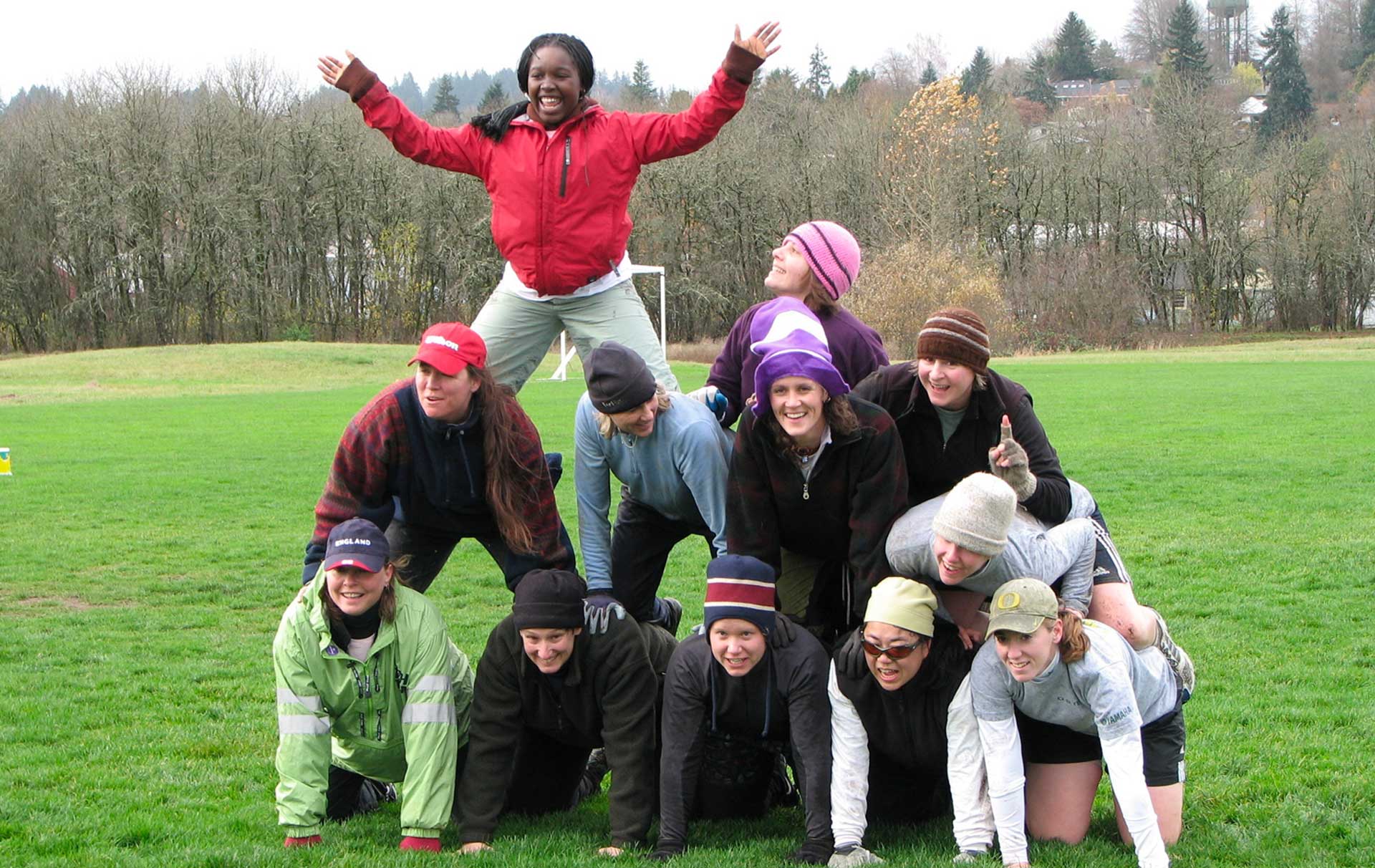

“In good lesbian fashion, we decided to play a sport,” she said. Touch football, with the “touch” in quotation marks.

“Being that especially women who have trauma histories and things where touch can be a real issue, we would check in ahead of time about if anybody didn’t want to be touched or tackled or whatever,” she said. “And then it was just kind of a free-for-all from there.”

Over two decades, the “Turkey Baster Bowl” grew from six people to about 100 at its peak. In time, Nemke started advertising it to queer people on social media. Transgender people, also barred from their family gatherings, started showing up. Long-time attendees came back with their children in tow. Nemke met her partner, Marnee Madsen Nemke, at the game that first year.

Even as some people’s families started opening their doors again, they found themselves going to play football before returning home. Many of the guests didn’t even want to play football. In some years, the fans outnumbered the players.

“There were well-established cheers,” said Nemke. “There were costumes. There were dance moves that would happen on the sidelines. … And I think that was what felt the most important was that we all had a place. Even if it was for two hours.”

As the pandemic keeps many families apart during the holidays, LGBTQ+ people are also adapting their traditions. But queer people, in particular, are adept at finding joy during the season with those immediately around them. Generations of LGBTQ+ people have been forced to.

The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey found that half of trans people faced rejection from the families they grew up with, spouses or children after coming out. One in 10 said that an immediate family member had acted violently toward them. LGBTQ+ youth are particularly vulnerable; they are 120 percent more likely to face homelessness, according to a study from the University of Chicago.

Even for adults who can’t go home, the days leading up to Thanksgiving and Christmas can be tough. They are for 35-year-old Brit Hanson, who is estranged from her family, not exclusively just because she is gay, though that is part of it. Hanson preps for the season by making sure she gets extra exercise and sleep.

“The thing that has really been a game changer for me is before the week of Christmas comes, or even at the beginning of the month, I just start thinking through what would be a really nice way for me to spend a day or that long weekend.” Hanson said.

It differs from year-to-year. Hanson, the associate producer on NPR’s “Short Wave” podcast who lives in Washington, D.C., used to work at the North Country Public Radio station in upstate New York.

“I loved working on Christmas, because people would call in with funny things, and I was like, ‘You know what, nothing makes me feel more meaningful than like being the person who answers the phone at the public radio station on Christmas morning,’” she recalled.

Dee Loeffler, a 39-year-old who also lives in D.C., historically chose a different Christmas adventure every year, often something they could do alone.

“In 2016, I spent Thanksgiving with friends and found it to be kind of an annoying experience, partly because I’m vegan,” they said. “A lot of non-vegans have a hard time feeding vegans.”

Loeffler didn’t have any Thanksgiving traditions tying them down — if anything, to them the holiday felt like a nod to colonialism — and they are estranged from their mom, which their dad struggles with. And so, the following year, they went to Ireland for the week.

“I started this kind of fun tradition for myself of picking a place to be for the week and then doing something especially fun on Thanksgiving Day,” Loeffler said. Thanksgiving became a treat for Loeffler, especially since for the rest of the world, it’s just another Thursday.

Matthew Carlton also found a way to treat himself over the holidays when he was 20 years old. It was 1997, and his family had been scattered abroad for work, love and military service.

“I went and bought a Stouffer’s dinner,” he recalled. Bored, he took himself to happy hour, where he found a different kind of holiday intimacy.

“There’s always a couple where one person doesn’t want to be in town, visiting the other one’s family, and the other person only came out of guilt,” he said. “You just wind up striking up a conversation.”

After all, “If you don’t want to be with the ones you love, love the ones who don’t want to either!” he joked.

Carlton’s family actually didn’t care that he was queer. His mom was an HIV/AIDS researcher. But he still found time with them “headache-inducing.” By the next year, Carlton, 43, had made his happy hour chats a tradition for most major holidays.

“There’s something about a sense of intimacy between a couple that’s been together a long time, that’s very secure in their relationship,” Carlton said. “That’s very comforting, and if you’re by yourself on a holiday, you kind of want something like that, or at least I did.”

The Nemkes have also revised plans for this reason. Their football cohort has reached their 50s and 60s, and many aren’t up to running the field anymore. The pandemic has also shrunk their world. Six years ago, Marnee suffered a traumatic brain injury that has left her in debilitating pain. But a saving grace has been the friends they made at the Turkey Baster Bowl.

“We’ve been able to really continue to draw on that community that we created to support us when we needed it after a lot of years of kind of being the ones who held the framework for other people to get support,” Kellie Nemke reflected.