This story is a collaboration with The Trace, an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit newsroom dedicated to shining a light on America’s gun violence crisis.

His daughter said that she and her boyfriend were coming home with some news. But as soon as they sat down in the living room that August day in 2016, John Reilly felt something was amiss. Rosemarie, usually goofy and gregarious, looked down at her feet. Her boyfriend, Jeremy, did all the talking. “We’re buying a trailer,” he said, adding that they had rented a lot in a suburban campground.

Nothing about this news felt right to 59-year-old Reilly, who had been waiting four years for his elder daughter to grow weary of her high school boyfriend. Rosemarie loved the bustle of her life near her nursing school in Grand Rapids, Michigan, but this campground was miles away from campus, surrounded by oak trees, grassy fields, and low-slung homes.

Sensing that his 21-year-old daughter had her own reservations, Reilly decided to weigh in: A hook-up trailer would not be the money-saving arrangement they imagined, he argued. It would lose value fast, and the cost of propane would be crushing in a region that gets 70 inches of snow in a typical winter.

But Jeremy Kelley was no longer the eager-to-please teenager who had first walked into the Reilly living room as a high school senior. Now 21, he responded to his girlfriend’s father in a voice that made the General Motors tradesworker’s breath catch: “At the end of the day, it’s my money, and I can do what I want.”

Two months later, Rosemarie was dead. On what would have been her 22nd birthday, when she was supposed to be enjoying a spa day with friends, she was laid out in a funeral parlor viewing room, where a small group sang “Happy Birthday” to her a final time.

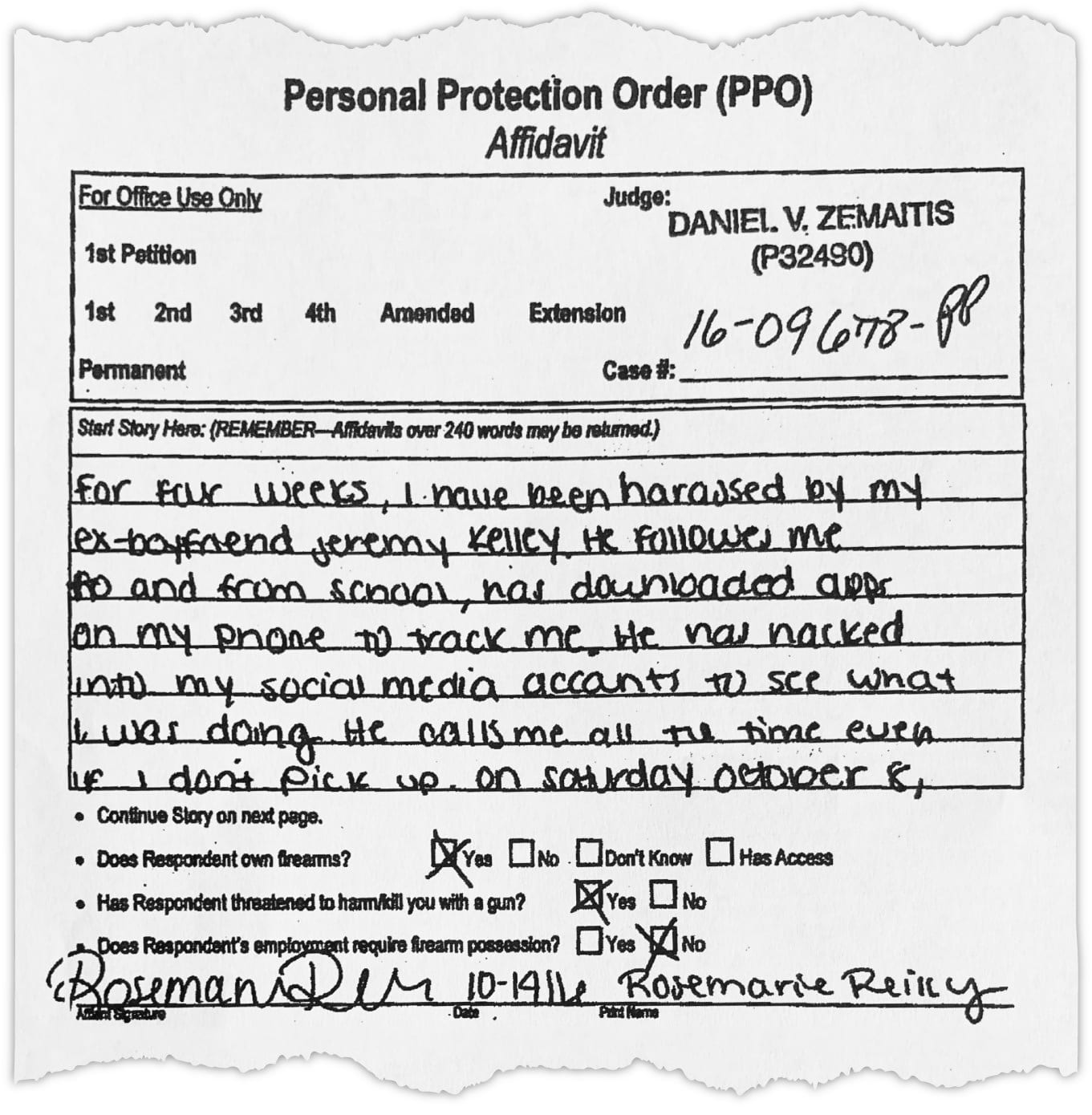

In an effort to save her own life, Rosemarie had asked a Kent County judge for an order of protection in October. In her affidavit, she noted that Jeremy owned guns and had threatened to shoot her. Judge Daniel V. Zemaitis approved the order, but he did not check the box that would have prohibited Jeremy from keeping his guns. In fact, of the 31 women who went to the Kent County Courthouse in Grand Rapids that month and swore that their partners had threatened to shoot them, only nine came away with protective orders that told their partners to relinquish their weapons.

The days immediately after an abused person files a restraining order are extremely dangerous. Twenty percent of people who were killed by partners and had restraining orders were killed by those partners within two days of the order being issued, according to one study. Thirty percent were killed within a month.

As gun sales surge and domestic violence incidents spike across the country due to nationwide unrest and fears related to the global pandemic, prohibiting someone who has been served with a protective order from keeping guns is a basic layer of defense the legal system can offer. Yet in 29 states and the District of Columbia, firearms restrictions aren’t automatically included in temporary orders of protection.

Michigan is one of 13 others where the decision to remove a gun is left in the hands of a judge. Last summer, Senate Democrats introduced a bill that would automatically remove guns from people who are subject to temporary protective orders in every state. The same provision was included in the The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019, which passed in the House of Representatives last year but stalled in the Senate. There’s a chance this will change with a narrow Democratic advantage in the Senate and Joe Biden, one of the original backers of VAWA, in the White House.

“Any reasonable person would say that a person dangerous enough to be ordered to stay away from his partner should not have a gun,” said April Zeoli, a professor of criminal justice who studies policies designed to reduce intimate partner violence and homicide at Michigan State University. “Yet in many cases, the guns aren’t being taken away.”

As a toddler, Rosemarie was wild and fiercely independent, often scheming to escape the house on her parents’ seven-acre farm. Her mother, Pam, struggled to keep her firstborn within reach. Sometimes, when the headstrong little girl took off down the gravel driveway, Pam had to jump in the tractor to catch her. Eventually, Pam learned to zip Rosemarie into a lifejacket as soon as she got out of bed in the morning; a little pond on their property was the only real danger, and with the lifejacket on, Pam could remain calm when her daughter fled. Sometimes, Pam would go looking for Rosemarie only to find her adrift in a rowboat with their elderly neighbor. He’d be chewing a cigar with a line in the water. Rosemarie would be playing with a bucket of bluegill, laughing as they wriggled and flipped in her small hands.

In school, Rosemarie — who went by the nickname Rose — needed that pluck to keep up. She had dyslexia and dysgraphia, learning disabilities that made it seem that letters were floating on the page. When she struggled to learn to read in elementary school, she begged her parents to give her a chance to catch up, rather than put her in a special education class. She sought out help from her teacher before and after school, and did eye exercises that helped her track text across the page. By the middle of elementary school, she had caught up to grade level. In high school, when she began struggling in calculus, she would take a public bus back to her middle school every afternoon, work her way through equations with a former teacher, and then return to her high school for softball practice.

Rosemarie was a natural caregiver even before she was old enough to fully care for herself. She frequently snatched her baby sister, Jennifer, out of the bassinet and brought her to her own bedroom, or arrived home after school with a stray cat tucked under her arm. In second grade, Rosemarie became friends with a girl who lived with a foster family. She told her mom that the girl’s clothes were stained and threadbare, and she didn’t seem to have any toys. “We have a big house and more toys than we can play with,” Rosemarie said. “We should bring foster children home to live with us.”

Soon, there were as many as six bassinets in the Reillys’ living room, each holding an infant affected by drug addiction or abuse. Rosemarie was around 9 then, and she would rush home from school, finish her homework, and spend the evenings holding and feeding the babies.

When a baby named Mia arrived at the Reilly’s home, Pam was afraid to pick her up. Only 8 weeks old, the infant had a fractured cheekbone, broken ribs, and a tiny body covered in bruises. She had learned that crying didn’t bring help, and she lay silent even when she was hungry or wet. Rosemarie was undaunted. She paced the halls with Mia at night, speaking softly into her tiny ear.

It didn’t seem unusual some years later when Jeremy showed up in the Reillys’ yard one night after a fight with his father, and their empathetic daughter asked her parents if he could stay. The Reillys had by then moved from the country to the Detroit suburb of New Baltimore, and their home, with its big open kitchen and overstuffed sofas, was a magnet for neighborhood kids.

Rosemarie knew Jeremy from a senior English class. On their doorstep, the tall, green-eyed boy was shaking and upset. His father had beaten him up, he said, pointing to choke marks on his neck.

Pam invited Jeremy in and called Children’s Protective Services — as a licensed foster parent, she was required to report any possible instance of child abuse. Then she made a bed for him in a spare room. He wound up staying on and off for four months. The young man was garrulous and good-natured. He cut the grass and cleaned the kitchen without being asked. He even built a vegetable garden for Pam.

Jennifer remembers seeing Jeremy’s eyes tracking Rosemarie as she moved around the kitchen. Next, she saw their hands touching as they sat together on the couch. One night, before Jeremy went to work at an auto mechanic shop, Rosemarie walked him out to the car. John followed and caught them kissing in the driveway. He teased them, but he didn’t interfere. His daughter was 17, soon headed to college. She was plenty old enough to date, and he and his wife had come to love Jeremy. Still, the two high school seniors seemed destined for different futures. Rosemarie had her eye on a big state university two hours west. Jeremy was already talking about trade school. John suspected that if he stayed mum, the relationship would fizzle.

After Rosemarie and Jeremy went to the homecoming dance together that fall, they came home, changed into jeans and T-shirts, and headed right back out to a party. As they raced out the door, John shouted, “No drinking, no drugs!” a frequent refrain that Rosemarie had always heeded. Half an hour later, Rosemarie was back home, alone. The party had been wild, she admitted, and Jeremy had been drinking. When Jeremy got in, he found his way to the bathroom and fell asleep leaning over the toilet. In the morning, John told Jeremy he’d gotten his one free pass. Next time, he’d kick him out of the house. A few months later, Jeremy came home smelling like alcohol, and John told him he had to leave.

In the fall of 2013, Rosemarie moved west to attend Grand Valley State University, which gathers 24,000 students on a campus of more than a thousand acres in Allendale, Michigan. But John’s prediction that the two teenagers would drift apart proved false. Rosemarie talked about Jeremy all the time, counting days between their visits. He bought her expensive gifts — Coach purses and jewelry. “This was the guy she was going to marry, for sure,” said Shelby Gird, one of her best friends at Grand Valley.

In 2015, after two years apart, Jeremy got his mechanic’s degree and joined Rosemarie in Allendale. She had been admitted to the school’s competitive nursing program after her freshman year. Shelby, who was in the same program, remembers when their class first went to a local nursing home to do clinical work, helping patients to eat, wash, and get out of bed. As they were brought in, most new students hung back in a cluster, feeling squeamish and shy about approaching the elderly residents. But Rosemarie walked up to each of them with a smile and a big hello, assisting without hesitation.

At first, Jeremy seemed to blend into Rosemarie’s new life. He got a $50,000-a-year job as a mechanic, and the couple rented an old house in town. Rosemarie hung an American flag from the porch and planted flowers beside the walk. They both worked long hours, her balancing her studies with two part-time assistant nursing jobs. On weekends, Rosemarie would go out dancing and to bars. Jeremy would often work late, but Shelby remembers that when she and Rosemarie lost steam, they’d call Jeremy, who would pick them up and bring them home, where Shelby crashed on the couch.

Any reasonable person would say that a person dangerous enough to be ordered to stay away from his partner should not have a gun.

April Zeoli, professor of criminal justice at Michigan State University.

Rosemarie was private when it came to romantic matters, but in 2016, the spring of her junior year, friends noticed that she stopped mentioning Jeremy as much. Jennifer overheard her sister having a tense phone conversation, and asked what was up. “He’s being a butt,” was all Rosemarie would offer.

The day in June that Rosemarie adopted Maggie, an orange tabby kitten, Rosemarie’s childhood friend Jenna Stancavage, who also went to Grand Valley, knew something had shifted. Ever since high school, Jenna had seen Rosemarie pour all of her love into Jeremy. Her choice to take in a kitten felt significant, like she was looking for a new place to put all that love.

Rosemarie didn’t bring the kitten home right away, but rather took it to her aunt and uncle’s house near campus. Her aunt, Noreen Axsom, remembers that when Jeremy stopped by and saw the kitten, he was furious that his girlfriend had adopted it without consulting him. Rosemarie held the kitten tight in her hands and circled from kitchen to dining room to den, and back again, as Jeremy followed, trying to make her look at him. Noreen didn’t think Jeremy was going to hurt her niece that day, but she remembers an electric tension between them that worried her.

A similar sense of unease overcame Rosemarie’s dad when she told him, two months later, that they were buying the trailer. Jennifer had started at Grand Valley that year, and the sisters were inseparable, walking to classes together, going to the gym, and meeting at the student center for dinner. Once she moved to the campground, Rosemarie and Jeremy would spend the winter months with only a few dozen other residents. John Reilly did not like thinking of his daughter alone, snowed in with a man who was starting to make her uncomfortable.

In September, just a few weeks after moving into the white Infinity trailer, Rosemarie told Jeremy she needed a break. Schoolwork demanded her full concentration, she said, at least through the semester. A few days later, Jeremy lost his temper after Rosemarie came home from seeing a friend. He held the barrel of his handgun to his head and threatened to pull the trigger, Rosemarie would later tell police. Then he walked outside the trailer and shot into the ground.

Rosemarie was calm and matter-of-fact when she told Jennifer and Shelby about her decision. She did not invite questions. She left most of her things in the trailer, but began staying more often in Jennifer’s dorm room or at her aunt and uncle’s nearby home. During that time, Rosemarie’s parents picked up when they saw Jeremy’s number. Pam and John loved the young man they had taken in four years earlier; perhaps they were the only adults who could help him. At one point Jeremy told John that he intended to propose, and he shared a photo of a diamond ring he had bought.

One night, Rosemarie and Jennifer walked together to their classes, which were in the same building. Rosemarie took Jennifer’s dorm room key, telling her she might leave during the break and go back to rest. She’d been up several nights in a row talking Jeremy down from a frenzy.

When class ended, Jennifer pulled out her phone and saw more than a dozen missed calls and texts from Rosemarie. As she walked down the cement stairs from the school building into the cool October night, she looked up and saw flashing emergency lights in a parking lot in the distance. Immediately, she knew it was Jeremy.

Jennifer ran toward the lights until she saw Rosemarie, standing in her light blue medical scrubs, talking to the police. Jeremy had called Rosemarie during her class and told her that he was going to shoot himself in the head. He was on campus, he said, and he had his pistol. Rosemarie begged him to calm down. Eventually, she hung up and called Jeremy’s father, Sean Kelley, thinking that Kelley, a police officer from a Detroit suburb, would know how to track his son’s phone using GPS. Kelley located his son and called Grand Valley campus police for help. An ambulance took Jeremy to the hospital; a frightened Rosemarie borrowed Jennifer’s car and met him there.

In the days that followed, the calls and threats got worse. On October 8, Rosemarie failed to show up for breakfast with her mom and her sister. When she called to cancel, Pam remembers, her voice was shaking. Later, she agreed to meet them at Uccello’s, an Italian restaurant in downtown Grand Rapids. As soon as she walked in, Pam knew something was terribly wrong. Rosemarie had red-rimmed eyes and bruises on her cheeks. Her nose was crooked. Rosemarie would not meet her mother’s eyes, but said that she had fallen up a flight of stairs. Pam didn’t press, but she told her daughter they were going to the hospital — her nose would need to be set.

On the way to the hospital, Rosemarie told her mom and sister what had happened. Jeremy had hidden her computer, on which she had several important assignments. She went to the trailer to look for it at a time when she thought Jeremy would be at work, but he had been lying in wait, tracking her phone using a locator app. When she arrived, he dragged her into his black pickup truck. He drove her up and down the dirt roads of the campground, hitting her as she sat trapped in the passenger seat. He brought her back to the trailer and pinned her to the bed, wrapping his hands around her throat and squeezing until her vision clouded. He put a pillow over her face. He held the barrel of his gun to her head, and then to his own, threatening to pull the trigger. In the silence that followed, she ran to her car and left.

As Rosemarie recounted these events, speaking calmly to her mother and sister, Jeremy was calling Pam’s phone incessantly. When they got to the hospital and Rosemarie went into an exam room with a doctor, Pam picked up. Jeremy admitted he had hurt Rose, and swore he would make things right. Pam told him that he and Rosemarie had to break up. But Rosemarie was still determined to protect Jeremy; she told the doctor she had gotten drunk and fallen down.

On October 11, as Rosemarie was looking for a quiet place to study, her phone lit up constantly with calls from Jeremy. She was confident he was tracking her phone, and, sitting at a traffic light at an intersection near campus, she saw Jeremy in his black Ford truck, driving toward her. Their eyes met. Rosemarie pulled into a parking lot that she knew was accessible only to students with parking passes. But Jeremy parked his car on the other side of the barbed wire fence and climbed over, begging her to talk “just two minutes.”A police report says Rosemarie tried to back away and accidentally ran over Jeremy’s foot. He fell down, crying, and she got out of the car to help him. Finally, he got into the car with her. He forced her to unlock her phone and delete her text messages. He made her disconnect from friends on social media.

Feeling trapped, Rosemarie decided the only way she could get away from him safely was to pretend he had convinced her to take him back. She put her promise ring on, accompanied him on a long walk, and agreed to meet him the following evening for a late dinner. Instead of meeting him, Rosemarie and Jennifer went to the campus police station. Rosemarie told an officer about Jeremy’s suicide attempts and his abuse. Because the allegations were so serious, the officer called in the Ottawa County Sheriff’s Office, who sent a deputy to interview her as well. As she told her story, Rosemarie wept openly. Evidence photos taken that night show her in her royal blue nursing scrubs, her nose still swollen, the corners of her mouth turned down. One photo shows a black bruise the size of a pear on her left bicep; another a round bruise the size of a tangerine on the back of her left thigh. The officer who spoke to Rosemarie told her to go to the Kent County Courthouse and apply for a protective order.

That night, Jeremy called Rosemarie’s Aunt Noreen more than a dozen times. With the phone still lighting up, Rosemarie arrived at Noreen’s house. She went to bed, apologizing for Jeremy’s behavior. Around midnight, Jeremy came to the front door. “He was pleading,” Noreen remembered. “He was desperate.” After about a half hour of speaking to Noreen and her husband, Dave, through the cracked door, Jeremy left. But he called a few minutes later and said he had a gun and planned to kill himself. Dave called the police. Even after they came, Dave slept fitfully: “I don’t own a gun, but I brought a golf club to bed that night, just in case.”

The Personal Protection Orders Department for Kent County, Michigan, is located on the third floor of a 13-story brick-and-glass building in the center of downtown Grand Rapids. Petitioners must ask a clerk for a form, then fill it out with an affidavit describing, in less than 240 words, why they feel threatened.

Many of the petitions are chilling. Stapled to one woman’s form was a photograph of a white suburban ranch house. Printed across the front were the words, “I FOUND YOU TERESA.” One case from a neighboring county showed printouts of screenshot after screenshot filled with the same text, each sent seconds after the last. “Did you change your mind yet/Did you change your mind yet/Did you change your mind yet.” On the second-to-last page, one message breaks the pattern: “When I quit sending you those you know I’m coming.”

On October 14, Rosemarie visited the office alone. She checked the box next to the words “Does Respondent own firearms?” She put another check mark in the box that asked, “Has Respondent threatened to harm/kill you with a gun?” In the narrative section, she wrote, in round, youthful print, “For four weeks, I have been harassed by my ex-boyfriend Jeremy Kelley. He follows me to and from school, has downloaded apps on my phone to track me. He has hacked into my social media accounts to see what I was doing. He calls me all the time even if I don’t pick up. On Saturday, Oct. 8, he hit me multiple times in the face, arms and legs. He strangled me until I couldn’t breathe. He told me if I left him that he would kill himself and ruin my life.”

Three days later, on October 17, Rosemarie picked up the protective order signed by the Judge Daniel V. Zemaitis, a family court judge she never met in person. Zemaitis had been instrumental in creating the city’s task force to combat domestic violence. But when he had approved the order prohibiting Jeremy from contacting, following, harassing, or harming Rosemarie for six months, he did not check the box that would have prevented Jeremy from keeping his pistol and two long guns.

In a recent interview with The Trace, Zemaitis said he did not remember the specifics of Rosemarie’s application for a temporary protective order, and he was not able to access her file because of restrictions related to COVID-19. But in general, he said, restricting the gun rights of the subject of a restraining order is complicated. He said some people get restraining orders for the wrong reasons, like to give them leverage in a divorce or custody case, and judges need to be cautious about restricting a person’s gun rights without sufficient evidence.

Rosemarie had checked a box asserting that Jeremy had guns and had threatened her with them, but she had not mentioned them in the narrative she wrote about his abuse. Zemaitis said that could have been a reason he didn’t order the restriction. “The narrative is what this thing is all about,” he said. “If someone doesn’t tell us there’s a gun involved, then there’s no gun involved.” He added: “The burden of proof is on the person who’s asking for [the gun restriction].”

But experts and advocates say it’s unreasonable to expect domestic violence victims to present their evidence perfectly during a terrifying situation. In Arizona — which, like Michigan, leaves gun restrictions on temporary protective orders up to judges — Tucson City Magistrate Judge Wendy Million said many domestic violence victims can’t organize their thoughts because of ongoing trauma and brain injuries stemming from being beaten or strangled. “They’ll write something down because it’s the thing that happened last night, but they’ll overlook the terrible thing that happened a month ago, like a threat with a gun,” she said.

Advocates also say that the bar is high for a person to get a temporary protective order for the time until a hearing. Proof that someone is a danger to another person should be enough to show that he should not have guns — at least for the days until a court hearing. They say if there is any doubt, it’s better to err on the side of saving a person’s life than preserving a person’s gun rights for a few days.

In eight states, including California, Illinois, and Massachusetts, the subject of a temporary protective order is automatically barred from having a gun. Whether authorities follow through to make sure that a gun is collected is a different matter, and it doesn’t always happen.

Thirteen states are like Michigan, leaving the decision in the hands of a judge. The Trace researched temporary protective orders in four such states and found that whether the subject of a restraining order is restricted from having a gun depends more on what county the subject lives in and what judge hears the case than on the strength of the evidence against them. The remaining states — 29 plus Washington, D.C. — have no process for taking guns away from the subjects of temporary domestic violence protective orders.

By failing to check a box on a form, Zemaitis dashed Rosemarie’s only hope of getting police to remove Jeremy’s guns.

On October 19, two days after Zemaitis signed the protection order, Jeremy found Rosemarie in a campus parking lot and followed her with his car. Jennifer remembers her sister running into the student cafeteria in her nursing scrubs, looking as terrified as a hunted animal. They went together to the campus police, who issued Jeremy a no-trespass order, took his photo, and told him not to come on campus for the next four years. Three days later, Rosemarie emailed the campus police to tell them that Jeremy had tried to call her 86 times in the previous five days.

Ottawa County Sheriff’s deputies, by this time, felt they had enough evidence to arrest Jeremy. They issued two warrants — one October 28 for domestic strangulation, another November 1 for stalking. What they did next is the basis for a federal wrongful death lawsuit Rosemarie’s parents filed against individual law enforcement officers for the university and county and the Ottawa County Sheriff’s Office. Rather than go to the trailer and take Jeremy into custody, they had mailed the warrants to him, asking him to turn himself in. The lawsuit claims that was because Jeremy’s father, who has since died, was a police officer in a different town and asked them to go easy on his son. A federal judge disagreed and dismissed the case, though the Reillys have appealed.

After more than a month of fielding desperate phone calls and looking for Jeremy around every corner, Shelby remembers that the night of Saturday, November 5, felt peaceful. Earlier in the evening Jeremy had called Rosemarie’s dad and said he’d gotten a warrant in the mail. He said he was out of town with his brother but planned to get a lawyer and turn himself in the following Monday.

Rosemarie’s extended family, including her aunt and cousins, went to a local restaurant that night to celebrate John’s 60th birthday. Rosemarie planned to stay with her parents at a hotel, in a room adjacent to theirs. The calls from Jeremy had slowed in recent days, and now it seemed like they may have stopped. When dinner was over, Rosemarie’s dad told her to go have fun with her friends. Rosemarie worked many weekends, so a night off was something to treasure.

Rosemarie and Shelby wanted to go dancing but found their favorite club empty. So they called Matt, a friend of Rosemarie’s from the hospital where she worked. They met at a sports bar, then walked back to Matt’s apartment, which was on the bottom floor of a big brick house, right in the middle of downtown Allendale. Shelby and Rosemarie squeezed into a white easy chair facing the front door, as they drank beer and traded stories with Matt and two of his friends. Rosemarie seemed at ease for the first time in weeks.

Sometime after midnight, Matt went out to buy vodka, leaving Shelby and Rosemarie alone with the two other young men. Shortly afterward, there was a knock on the door. Shelby and Rosemarie both laughed at the sound, assuming it was Matt playing a joke on them. Rosemarie stood up and walked the few feet to the curtained glass front door. When she pulled it open, Shelby heard Rosemarie yelp. Jeremy, standing on the front porch, grabbed Rosemarie by her hair and dragged her outside. Through the open front door, Shelby saw Rosemarie momentarily break free and turn back toward the house, terror in her eyes as she tried to escape. Then Shelby heard several loud cracks as the glass in the door shattered. She saw her friend fall, face down.

One of the boys, Andrew, grabbed Shelby’s arm and pulled her back through the house. They ran out a back door and climbed into Andrew’s car, locking the doors. Andrew called the police, though Shelby can remember nothing about what he said. When police arrived, they put them in the back of a cruiser, where they waited for what seemed like hours. As Shelby ran her fingers over the plastic-covered back seat, she remained in denial about what she had just watched. She remembers saying, “Wait, where’s Rose? Is Rose okay?” Police told her that Rosemarie was dead, and that the man who killed her had also killed himself just feet from where she lay.

At 3:15 a.m., Pam Reilly woke with a start in the hotel room. She called Rosemarie’s cell phone, and it went immediately to voicemail. She woke her husband. “She’s asleep in the next room,” John assured her. But about 8 a.m., two police officers appeared at their door to say their daughter had been killed. Noreen arrived at the hotel a short time later, and she remembers John sitting in a chair, his eyes squeezed shut. Pam, sitting on the bed, was rocking back and forth saying, “He killed my baby.”

Today, Rosemarie’s parents ask themselves and each other in a hundred ways what they could have done to save their oldest daughter. Pam, who works part-time as a volleyball referee, has found herself reliving the last days of Rosemarie’s life when she is supposed to be calling fouls. Should she have taught her daughter to be more hard-hearted? Were she and John wrong to take Jeremy in? Should they have objected when they began dating? “I taught her to love people who needed love, and it wound up killing her,” Pam says, her voice breaking.

Douglas Van Essen, a lawyer who represents the Ottawa County Sheriff’s Office, said deputies would not have had the authority to take away Jeremy’s guns. Besides, a person desperate enough to kill himself will not be deterred by a protective order, whether it has a gun restriction or not, Van Essen said. “With more guns than people, anyone in the U.S. who wants to get their hands on a gun can do so,” he said. A spokesperson for the Grand Valley State Police said she could not comment because the lawsuit is ongoing. But James Rasor, who is representing the Reillys in the wrongful death lawsuit, says the wonder of Rosemarie’s story is that she did everything right: She and her sister and parents called the police about Jeremy at least 15 times over six weeks. She went to court for a protective order. She called the police when he violated it. She asked them to take his guns.

Rosemarie’s body was laid to rest in a mausoleum near her parents’ home in November 2016, in a service that her parents are still struggling to pay for. Days later, Noreen went into her son’s room — the room where Rosemarie had lived in the final days of her life. Rosemarie’s clothes were still on the bed, and her coffee cup on the desk. There were papers, textbooks, and notes she’d written on Post-its. On the desk by the door, there was a sparkly blue spiral notebook. Cautiously, Noreen opened it. There was Rosemarie’s bubble print. “I just want to be independent,” Rosemarie had written. “I just want to live by myself in my own place. I just want to start my life.”

Additional reporting by Melanie Plenda, Claude Akins, and Jared Kaltwasser.