Lawmakers in several statehouses this year want to stop lesson plans that focus on the centrality of slavery to American history as presented in the New York Times’ 1619 Project, previewing new battles in states over control of civics education.

Republican lawmakers in Arkansas, Iowa, Mississippi, Missouri and South Dakota filed bills last month that, if enacted, would cut funding to K-12 schools and colleges that provide lessons derived from the award-winning project.

Some historians say the bills are part of a larger effort by Republicans, including former President Donald Trump, to glorify a more White and patriarchal view of American history that downplays the ugly legacy of slavery and the contributions of Black people, Native Americans, women and others present during the nation’s founding.

Political battles have long been fought, largely in education boards, over how American students learn about everything from the Civil War to ethnic studies and health. But proposed legislation that would penalize schools for teaching curriculums based on the 1619 Project signals a new era of policy debate over civics education that may increasingly play out in state legislatures.

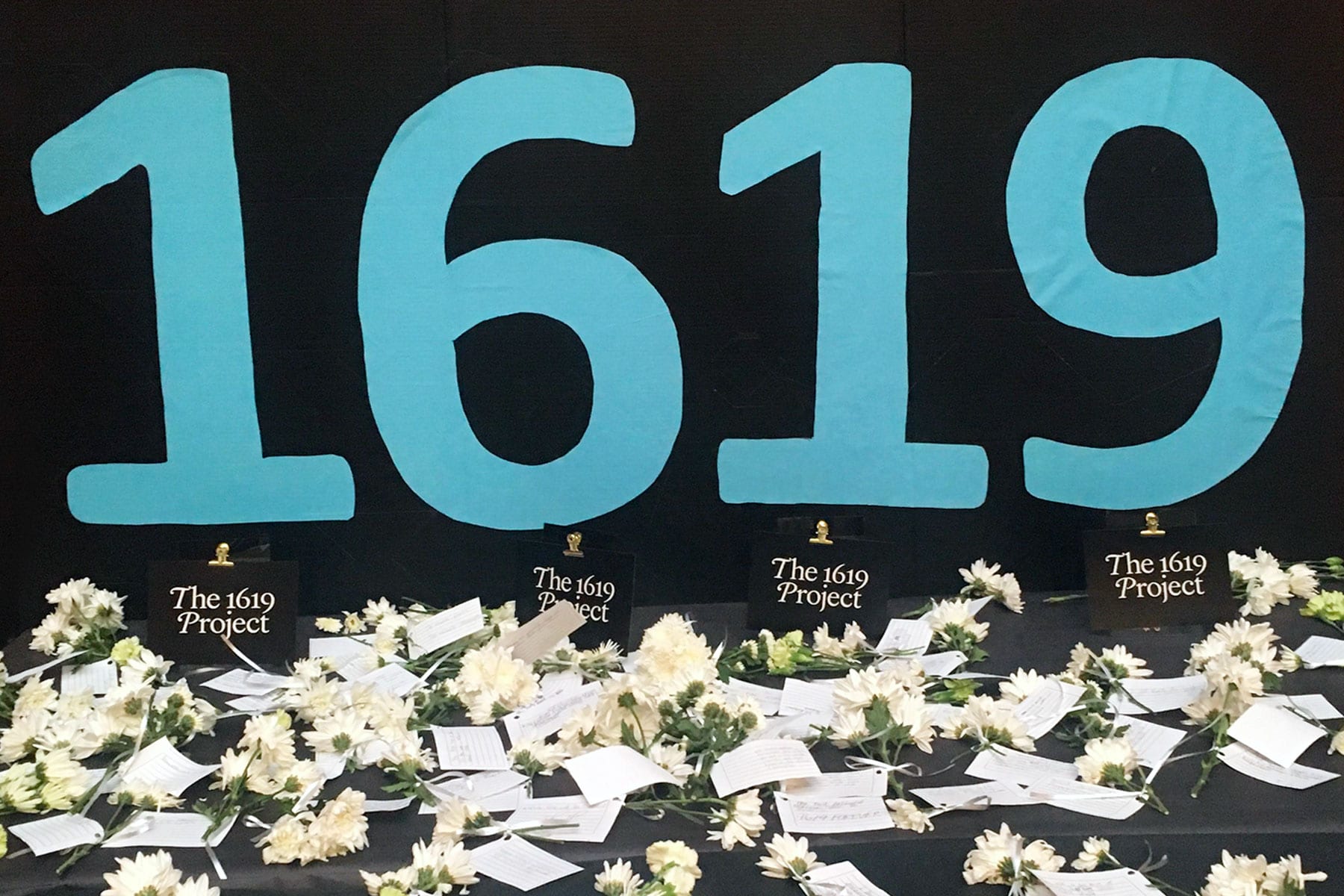

The project, which was first published in the New York Times Magazine in 2019 and for which its creator, Nikole Hannah-Jones, won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary, marked the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first known enslaved Africans in the British colonies that became the United States. It includes audio, essays, poems, graphics and visual art pieces that reframe the legacy of slavery in contemporary American life, arguing that Black Americans are the foundation of U.S. democracy.

The Pulitzer Center, in partnership with the 1619 Project, has made available related lesson planning and says more than 4,000 educators from all 50 states have reported using its resources. While some historians have criticized parts of the project, the Times has stood behind it (a more recent editor’s note further defending the project acknowledges that the newsroom’s separate opinion section has published pieces against it), and other historians have praised the project’s approach and rigor and treatment of the role of white supremacy in U.S. history.

Experts in history criticized Republican legislators for supporting bills that make such an overt move to force teachers to gloss over parts of U.S. history. It comes after a year in which many Americans have protested systemic racism within U.S. institutions, and education has not been immune from that conversation. Top Republicans, including Trump, have expressed support for nationalist propaganda, as well as the preservation of racist monuments.

“Do we want historical facts and details that are researched and published by experts taught? Or do we want nationalism taught?” said T. Jameson Brewer, an educator and assistant professor at the University of North Georgia. “That’s a very scary sort of suggestion, that schools would engage in ideological nationalism for political needs.”

The anti-1619 Project bills (which come after U.S. Republican Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas filed related legislation last July) are brief and use similar or identical language. The legislation out of Arkansas and Mississippi both call the project “a racially divisive and revisionist account of history that threatens the integrity of the Union by denying the true principles on which it was founded.” The Iowa bill expands its threat to school funding by suggesting any teachings with “any similarly developed curriculum” could face repercussions. The Missouri bill prohibits teaching, affirming or promoting claims, views, or opinions presented in the 1619 Project as “an accurate account or representation of the founding and history of the United States of America.”

Some Republican governors have also proposed using state money to shape how history is taught.

In November, Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves proposed spending $3 million on a “Patriotic Education Fund” that would allow schools and nonprofits to apply for money to provide teaching that “educates the next generation in the incredible accomplishments of the American Way.” In a budget proposal, he wrote: “Across the country, young children have suffered from indoctrination in far-left socialist teachings that emphasize America’s shortcomings over the exceptional achievements of this country.”

In South Dakota, Gov. Kristi Noem last month proposed spending $900,000 for a curriculum that teaches the state’s students “why the U.S. is the most special nation in the history of the world.”

Trump also tried to push “patriotic” education, creating a “1776 Commission” that released a report on Martin Luther King Jr. Day that was criticized for its inaccuracies and erasure of Black people, Native Americans and women and was quickly taken down by President Joe Biden after he took office.

“I think what we’re seeing is a right-leaning or Republican state sort of picking up the reins as it were, trying to push forward with that exact same agenda, just at the state level,” said Brewer.

James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association, which represents more than 12,000 historians, has been tracking the anti-1619 Project legislation. He expressed concern about efforts at the state level to elide the roles of racism and white supremacy in American history.

“You cannot heal divisions by pretending they don’t exist,” he said. “The way to address divisions is to understand the history of those divisions.”

Grossman added that curriculum proposals that appear to be ideological are an attempt “to deal with a perceived sense of ‘This isn’t my country anymore,’ by making it into something that never really was.”

Koritha Mitchell, an associate professor of English at Ohio State University, noted that several of the bills include language that seeks to address the 1619 Project as a “revisionist,” racially divisive framing of history. But, she said, race does not intertwine with history only when people of color are involved.

“That’s one of the main ways this White-washing of history happens. We don’t even call it Whiteness. We call those heroes. Founding Fathers. Americans. Pioneers. We pretend Whiteness has nothing to do with those laudable labels,” she said.

Mitchell said the legislation on the statehouse level is aimed at sending a message at a time when Republicans hold more majorities than Democrats in the statehouse but have lost control in Congress.

“There’s more leeway at the state level to do something to put people who aren’t straight White men ‘back in their proper place,’” she explained. “And whether they succeed or not, it is important that they’re flexing that muscle of reminding people, ‘No, no, no. This is still the United States. Where the people who belong in power are straight White men.’”

It’s unclear if any of the anti-1619 Project bills will become law. Phil Jensen, a Republican representative who filed the bill in South Dakota, told The 19th in an email that he has withdrawn the legislation and is focused on other work, including a resolution that celebrates Black History Month.

“I have chosen to withdraw that bill as I do not feel that I can adequately address it as well as I would like to at this time,” he wrote.

Jensen’s Black History Month resolution, which downplays America’s involvement in slavery in part by claiming the country has a “positive record on race and slavery,” has also been publicly criticized.

Skyler Wheeler, a Republican representative who introduced the bill in Iowa, said in a statement: “The Legislature absolutely has an interest in preventing racist, divisive, historically and factually inaccurate, and politically driven propaganda masquerading as history curriculum from being used in taxpayer-funded schools.”

The Republican lawmakers who sponsored the other bills did not respond to requests for comment.

Grossman noted that in the 1950s, some legislators monitored textbooks to see how the Civil War was being taught and teachers were accused of being communists.

“This has a long history in a way, of the most conservative aspects of American political culture jumping on teachers and education curriculum and caricaturing it as being somehow unpatriotic,” he said.

A decade ago, lawmakers in Arizona passed a bill prohibiting Mexican-American studies. A federal judge in 2017 ruled the law was enacted for racial and political reasons, making it unconstitutional.

Mitchell credits Hannah-Jones, also a staff writer at the Times, for the 1619 Project having a profound impact on some people’s foundational understandings of American history.

“It’s a backlash to her success at getting ordinary Americans to hold themselves to higher standards,” Mitchell said.

Hannah-Jones, a Waterloo, Iowa, native who expressed disappointment about a bill being introduced in her home state, told The 19th that she doesn’t believe the lawmakers who have filed these statehouse bills have actually read the 1619 Project. She encouraged them and others to read the initiative before deciding how they feel about it. Hannah-Jones also said that no matter one’s politics, she hopes people can agree that an education is about introducing differences in opinion and challenging perceptions.

Michèle Foster, an education professor at the University of Louisville, said much of what she learned about slavery she got from her family, not school. She sees a connection between the Capitol riot on January 6 and the slate of bills filed, linking them to fear of a changing country.

“I think there are historical and societal conditions that give rise to this fear, and one way to deal with fear is to pass legislation that restricts it,” she said. “Because that way you feel like you can control what people learn, and then you can have the status quo.”

This story has been updated to add additional context about the South Dakota resolution on Black History Month.