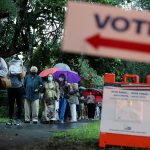

Rosemary McCoy didn’t vote in the 2020 election — she couldn’t. Instead she put boots to the ground in Duval County, Florida, asking people if they would exercise their right to vote because she had been disenfranchised. “Is it possible for you to go out and vote to support me?” McCoy asked.

After nearly two-thirds of the state voted to restore the right to vote to those convicted of felony offenses, McCoy and more than 700,000 Floridians lost access to the voting box in 2019, when Gov. Ron DeSantis signed Senate Bill 7066 into law. The legislation requires formerly incarcerated people to pay any restitution, fines, fees or court costs — also known as legal financial obligations — before regaining the right to vote. McCoy learned that she owed about $7,500 in victim restitution, including interest, and her county expected her to pay it all at once. Advocates call the law a modern-day poll tax.

Now, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), which sued Florida on behalf of McCoy and another Black woman named Sheila Singleton, is asking an appeals court to require a new analysis of the nation’s sole felony disenfranchisement lawsuit alleging a violation of the 19th Amendment. Lower courts dismissed SPLC’s analysis of the law’s disproportionate financial, “undue burden” on women of color.

“It’s sad that here we are in 2021, and we’re still discussing this same issue,” McCoy said. “There’s only one purpose of taking your voting rights away from you, and that is so that you can be a slave. No one can change my mind about this … If a woman is a slave, her children and grandchildren are a slave.”

The SPLC accused the state of violating constitutional amendments that bestowed voting rights to the formerly enslaved and violating the 19th Amendment, which gave some women the right to vote.

The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Florida’s felony disenfranchisement laws in September, but, according to court documents filed on February 10, McCoy’s lawyers want the court to weigh in on The 19th Amendment more directly because of the law’s disparate impact on women of color.

At the core of this renewed legal battle is the question of intent. Lawyers for the state of Florida argue that McCoy and her legal team have to prove that lawmakers and the governor intended to disenfranchise women with the law. But Nancy Abudu, the deputy legal director for the SPLC, filed an appeal for Florida to focus on the impact of this law on women of color.

“We have to move away from having to prove that people are racist and sexist,” Abudu told The 19th. “If that is our burden of proof, then we might as well not bring any of these cases. Instead, we need to focus on what is the impact of these laws. You can’t feel comfortable with a system that incarcerates mostly poor Black people just because the system doesn’t say arrest poor Black people.”

Attorneys representing DeSantis and Florida’s secretary of state did not respond to a request for comment at press time.

Nationwide 57 percent of men made less than $23,000 prior to incarceration, this is true for 72 percent of women, court documents read. The SPLC’s past filings include data from Prison Policy, a nonpartisan criminal justice think tank, showing the unemployment rate among formerly incarcerated people between the ages of 35 to 44 was 44 percent among Black women and 35 percent for Black men, and 23 percent among White women compared to 18 percent of White men.

Abudu sees this as a timely fight. Black women’s votes ushered in the first ever woman in the White House, and Black women like Stacey Abrams, who’ve been largely uncredited with this work, became household names. Yet laws like Florida’s felony disenfranchisement law have the heaviest burden on Black women, Abudu said.

“Our argument essentially is that because of that legislative history, and because of the political history of Black women and voting in our country, that that leads to the conclusion that Black women, or women of color in general, need greater protection when it comes to their voting rights,” Abudu said.

As the SPLC argues in new court documents, the 19th Amendment claim should be read in a way that grants the greatest protection to women, especially because when Congress passed it in 1920, it hardly enfranchised all women.

“The aim of enfranchising women was not simply so they could cast a ballot, but so they could directly influence the other areas of life that ultimately infringe upon their right of self-determination,” the lawsuit reads.

This aspect of widening what voting means to women is pertinent for McCoy, who’s teaching her 6-year-old grandson about financial literacy and cryptocurrency as the Florida legislature entertains arguments about excluding formerly incarcerated people from the state’s $15 minimum wage increase.

“If I can’t vote, it’s hard for me to guide the direction of my grandson,” McCoy said. “I need to vote. I need to vote for things that matter to my family, my community, my state and the United States of America.”