Since early December, President Joe Biden has vowed to make reopening public schools — which have struggled to provide in-person learning since the onset of the pandemic — a top priority.

But even as more Americans get coronavirus vaccines, the past few months have been riddled with uncertainty on the question of in-person schooling — in particular what exactly “reopening” means. The president is also limited in what he can do, especially without the full backing of both Congress and state and local governments. Some schools are fully open for in-person learning, some are relying completely on virtual school, and many are using a hybrid model that combines both.

Many parents have been tasked with stewarding their children’s virtual education, with mothers in particular dropping out of the workforce to supervise their kids’ learning full-time. And teachers, who are mostly women, have navigated remote and hybrid schooling systems that are unpredictable, psychologically draining and, virtually all agree, less effective than full in-person learning.

Meanwhile, it’s still impossible to find clear answers about when and how kids will be back in the classroom full time.

Members of the administration have offered sometimes conflicting definitions of what “opening schools” means, even as they provide guidance that suggests a long road lies ahead for parents and teachers. Here’s what the administration has said:

December 8: Biden, who hadn’t yet assumed office, said getting kids “back in school and keeping them in school” should be an immediate priority.

“If Congress provides the funding, we need to protect students, educators and staff. If states and cities put strong public health measures in place that we all follow, then my team will work to see that the majority of our schools can be open by the end of my first 100 days,” Biden said in that speech.

December 29: Biden called “opening most of our K-8 schools” a goal for his first 100 days, omitting high schools, whose older students appear more likely to spread COVID-19.

January 21: In an executive order, Biden directed his secretaries of education and health and human services to start working on recommendations for schools to figure out when and how to safely reopen. Neither of Biden’s nominees for those positions has yet been confirmed by the Senate.

February 9: Press Secretary Jen Psaki said the administration was pushing for a majority of schools to be open “at least one day a week.”

That would mean leaving those schools in a so-called “hybrid” model, mixing in-person learning with virtual. About a quarter of schools adopted a hybrid approach at the start of last year, though it’s not clear how many stuck with that strategy, especially as COVID-19 cases soared through the winter. The federal government does not have data indicating how many schools are already in a hybrid approach.

February 12: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released its own roadmap for what it would take to safely reopen schools, either in a hybrid model or fully in person. Per that document, counties with high levels of community COVID-19 transmission — more than 100 new cases per 100,000 people in the past seven days, or test positivity rate higher than 10 percent — aren’t necessarily ready for full in-person learning, even for younger children.

As of February 17, about 75 percent of jurisdictions are in those high-transmission zones, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky said.

The CDC advises that schools in those counties require maintaining six feet of distance between people in schools, a guideline that would necessitate teaching smaller groups of children at a time, which indicates a hybrid model could be necessary.

“CDC is not mandating that schools reopen,” Walensky told reporters on February 12.

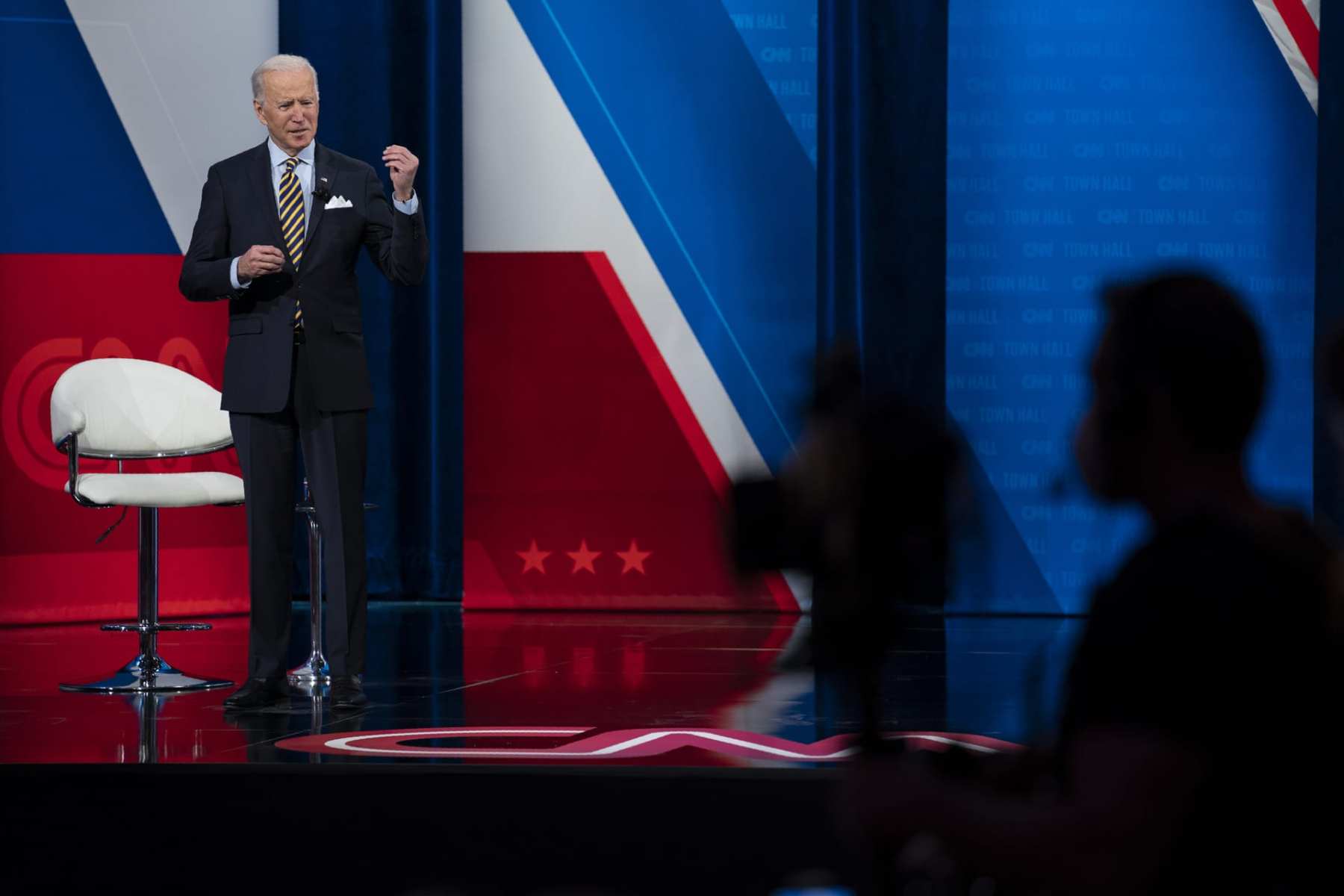

February 16: Biden revised his timeline at a CNN town hall, saying that the administration would “be close to” having K-8 schools open five days a week by the end of his first 100 days in office.

“Many of them are five days a week. The goal will be five days a week,” Biden said at the town hall.

Meanwhile, the important variables allowing schools to reopen aren’t fully up to the president. The emergence of new, more contagious coronavirus variants — including the B117 strain, which was first seen in the United Kingdom and is expected to be the dominant U.S. form of COVID-19 by March — could change the guidelines once again, Walensky said last week.

“If we get to a point where we are beyond the red zone — really high levels of community spread related to these variants or related to more transmission — we may need to visit this again,” Walensky said.

Other factors could curb community spread of the virus, including mask mandates and limitations on indoor restaurant dining, gyms and houses of worship. (Many preventable outbreaks from last summer have been traced to bars and restaurants.) But those don’t fall within the president’s control. So far, 15 states do not have any laws requiring that people wear masks in public, despite the role they play in curbing coronavirus spread.

Meanwhile, Biden’s COVID rescue plan includes $130 billion to support reopening schools safely, including money for regular testing and for making sure schools have up-to-date ventilation systems, which experts agree are critical in keeping people safe when they are indoors. The plan is still making its way through Congress. (On February 17, the administration announced it was directing $600 million toward promoting testing for schools as a “pilot” until the plan is passed.)

The CDC says teachers do not need to get vaccinated against the coronavirus before returning to full in-person learning, as long as schools implement other disease prevention strategies — such as universal masking, diagnostic COVID-19 testing, and regular hand-washing and cleaning.

The CDC does encourage states, which are in charge of distributing immunizations, to prioritize teachers for vaccines. Currently, at least 28 states and the District of Columbia have prioritized at least some teachers for early vaccines.

Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris have also said they support states prioritizing teachers but also do not believe it is a necessary prerequisite for reopening, Jeffrey Zients, the White House coronavirus response coordinator, said February 17.

A poll by the American Federation of Teachers, one of largest educator unions, found that most teachers also support going back to in-person learning — assuming schools have in place measures to prevent the spread of disease, such as those endorsed by the CDC, and if teachers are made a vaccination priority group.