*Correction appended

Nearly 500,000 women returned to the workforce in March, while 117,000 men left, according to new data released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics on Friday. Women-dominated industries, including leisure and hospitality, are beginning to bounce back just as students who have been learning remotely for months return to in-person classes.

As more states lift restrictions on businesses, vaccine distribution continues and direct payments of $1,400 make their way to most Americans, the end of the economic fallout of the pandemic appears to be in sight.

At a press conference on Friday, President Joe Biden called the most recent jobs report “promising” after a “year of devastation.” The first two months of his administration has seen more jobs created than any other administration’s first two months, he said, but there are still more than 8 million fewer jobs today than last March.

“Too many women have been forced out of the workforce,” Biden said. “Unemployment among people of color remains far too high … Today’s report is good news. It shows what the country can do when we act together to fight a virus, to give working people the help they need. But we still have a long way to go.”

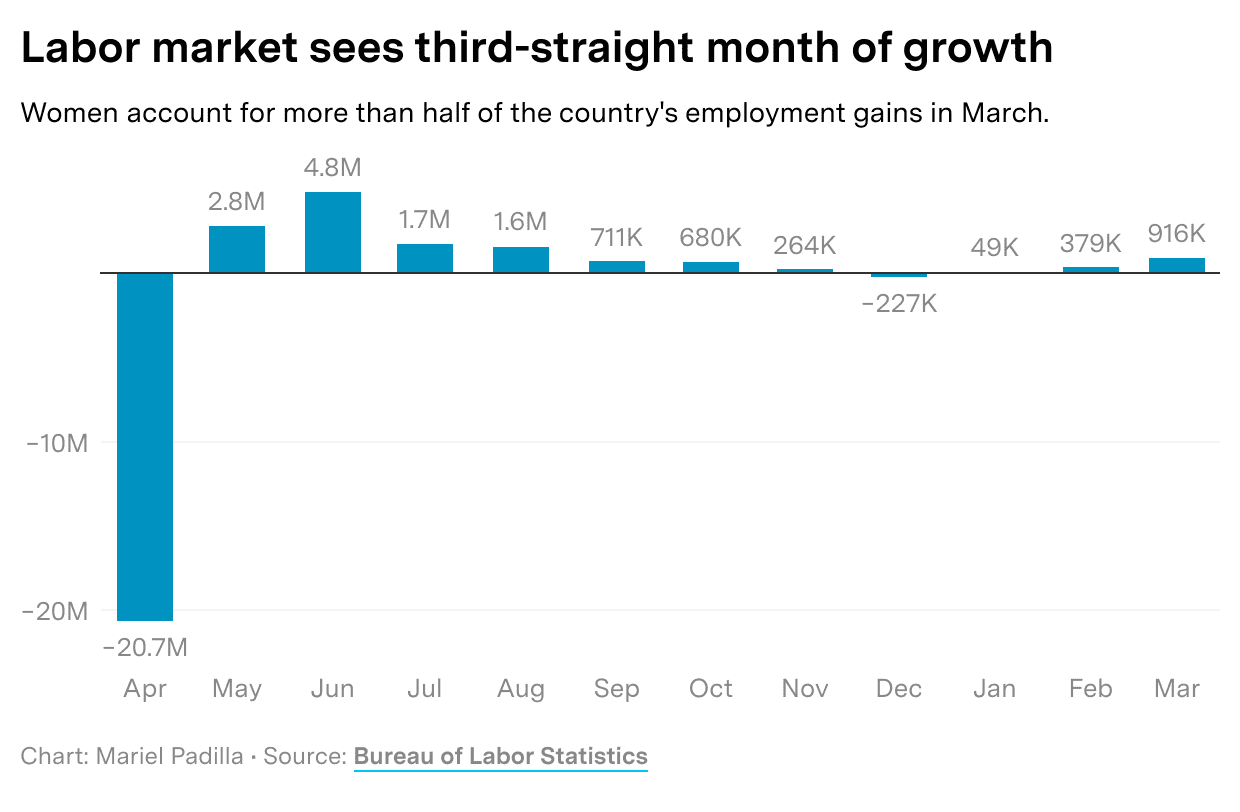

According to the data, the total number of net jobs gained last month was 916,000, according to data that surveyed employers. (BLS uses two surveys, one surveying establishments and one surveying households, to formulate a picture of the status of the U.S. economy). The labor force includes both the employed and unemployed — people who do not have a job but have actively looked for one in the past four weeks, according to the bureau. Those out of the workforce are those who don’t have a job and aren’t looking for one.

The leisure and hospitality industry — which was hard hit by the pandemic and responsible for some of the heaviest losses to women’s employment — added 280,000 jobs in March. Employment also rose nearly 200,000 in public and private education, another sector comprised predominantly of women.

The pandemic has caused an unequal recession, and some groups have started to bounce back more robustly. White women’s unemployment rate is 5 percent and for White men, it’s 5.2 percent, edging closer to the pre-pandemic rate of about 3 percent for White men and women.

But unemployment rates across the board remain higher for women of color. For Black women, the unemployment rate is 8.7 percent and 10.2 percent for Black men — a dramatic increase from 5.3 percent and 7.6 percent respectively in March 2020. For Latinas, the unemployment rate is 5.9 percent and 6.2 percent for Latinos. For Asian women, it’s 5.7 percent and 6.1 percent for Asian men, according to the data.

Women appear to have recovered from the drop in September 2020, when 865,000 women left the workforce. Their exodus was prompted by the start of school, child care challenges and various pandemic restrictions that upended many of their lives. However, there is still a long way to go before women gain back the nearly 11 million jobs that disappeared between February and May of last year, which marked the country’s first women’s recession.

Michael Madowitz, an economist at the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank, said that the country’s employment rate likely won’t return to pre-pandemic levels until at least 2022, even given this historic pace of growth.

“The employment rate for women has partially recovered from its April 2020 low, but only enough for women’s employment to increase from late 1970s levels to late 1980s levels,” Madowitz said in a statement.

With about 4.1 million people who have been out of work for more than six months, there are now more people experiencing long-term unemployment, both in and out of the labor market, than at virtually any other time in U.S. history.

The longer that workers are out of the labor force, the harder it is for them to rejoin it, particularly in a similar position or for similar pay as before. Because women are more likely to be out of work than men, this is expected to exacerbate the gender pay gap.

“Many mothers of young children are facing burnout and an unemployment crisis,” Madowitz said. “They may now face decades of increased wage discrimination over resume gaps and missed promotions during this impossible year.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article mistakenly stated the number of men who had joined the labor force in March. The headline and story have been updated.