Earlier this month in Portland, Oregon, a group of people spoke at a public hearing about the dignity of their jobs as sex workers.

One person at the hearing, organized by the Oregon Sex Workers Human Rights Commission, said that as a single parent, sex work had provided a level of financial stability that other jobs did not. Other fields offered low wages that made it difficult to provide the bare minimum in terms of food and housing.

“I’m able to buy food, my kids’ school supplies, give them presents on Christmas morning and not have the fear of being homeless,” said Brandi, who only provided a first name. Brandi began to cry: “Law enforcement says I should get a real job, as if I don’t have a real job.”

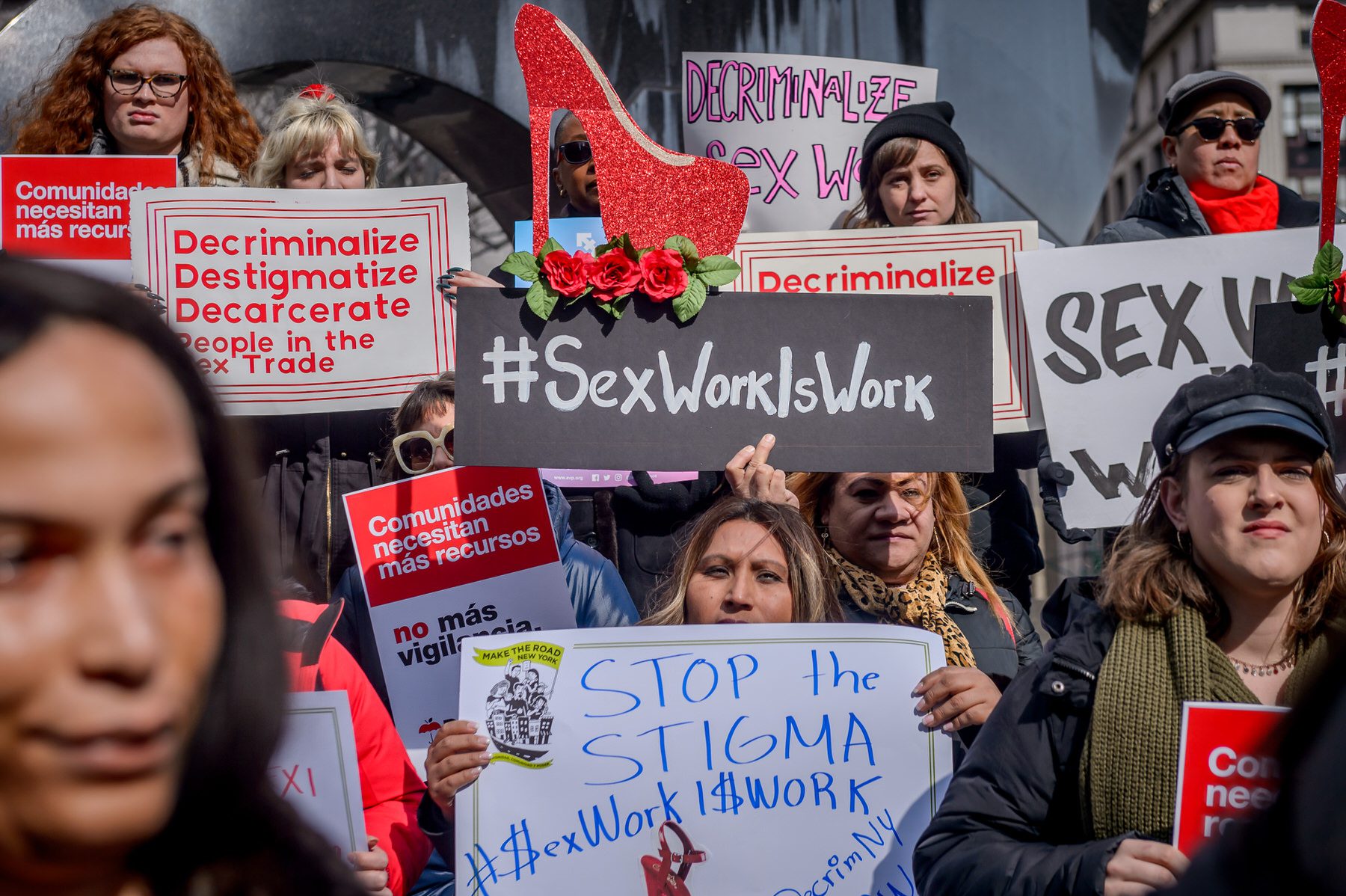

Prostitution — the term in many state statutes that prohibits people from engaging in sex for money — and sex work are increasingly coming up in policy debates around the country, as local and state officials seriously consider how to address the long-term harmful effects of criminalizing it.

Federal law bans engaging in sex for money, and there are a range of state criminal charges for prostitution, which can impact future housing and employment prospects. More and more frequently, officials are considering a world in which sex work is decriminalized. Two states in particular, Oregon and Maine, preview the diverging paths on how to get there.

A bill in the Oregon legislature was introduced this year that would repeal criminalization of prostitution and commercial sexual solicitation for both the buyer and seller of sex. In Maine, a bill introduced this year proposed only partial decriminalization of prostitution — unlike full decriminalization, it would have still subjected people who pay for sex to legal repercussions.

The Oregon bill did not advance out of a committee in the Democratic-controlled legislature. And while the Democratic-led Maine legislature passed its bill out of both chambers, Gov. Janet Mills vetoed the measure at the end of June.

The two bills marked out two different futures, but also revealed the many conflicting ideas on the future of sex work. As policy ideas increasingly move ahead in statehouses and city councils, the dynamics of the debate are fraught. Even the terminology is debated: Not all people who engage in sex for money call themselves sex workers, and not all sex workers describe their work as prostitution.

“It is complex, it is messy, and it is a conversation that is surfacing on a daily basis, at every level,” said Taina Bien-Aimé, the executive director at the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, which supports partial decriminalization of prostitution that penalizes sex buyers.

Prostitution is illegal in every U.S. state but in a handful of Nevada counties, where it is regulated through registered brothels, but the past decade or so has seen movement toward further decriminalization. San Francisco in 2008 was one of the first serious test cases of whether to decriminalize prostitution, but voters rejected the measure. More than a decade later, the city council in the District of Columbia debated for more than 12 hours whether to do the same in the nation’s capital. The council did not advance the proposal. Here are other actions in recent years:

- New York this year repealed an anti-loitering law known as the “walking while trans” ban. Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed the bill into law in February.

- New York and Massachusetts are considering partial decriminalization bills. New York is also considering a full decriminalization bill.

- The Seattle City Council last year repealed a prostitution loitering ordinance.

- The Rhode Island Legislature agreed this month to carry out a study to review the state’s laws on sex work. (The state briefly decriminalized indoor prostitution from 2003 to 2009, a move that lawmakers say was an accident because a key provision in state statute was deleted in bill drafting).

- New Hampshire passed a bill that would allow someone to be immune from prostitution-related charges if they report an incident of alleged assault. Gov. Chris Sununu signed it into law in June.

- The Burlington City Council in Vermont voted this month to consider eliminating ordinances that prohibit prostitution. Final action is expected in a few months.

People who are paid for sex are disproportionately cisgender women and trans women of color. (Girls are also disproportionately impacted, but people under the age of 18 who are paid for sex are legally considered victims of human trafficking. Human trafficking is the use of force, fraud or coercion to obtain some type of labor or a commercial sex act.)

Many gender justice advocates agree that decriminalization for people engaged in sex work will help them access health care services and ensure safety. Sex workers often fear contacting law enforcement because of potential criminal charges and jail time, as well as potential abuse from officers. Some have not sought health care services because of stigma or fear of losing their children.

But here’s where opinions vary. Some people see a direct correlation between people who are paid for sex and human trafficking, with some believing that any engagement in sex work is a form of exploitation and full decriminalization will lead to increased demand for it. Supporters of sex work, meanwhile, say law enforcement and others unfairly conflate human trafficking and what they describe as consensual sex with clients. They believe it’s something they should be able to choose to do.

Two months before the public hearing in Portland, Oregon, Nicole Bell logged into a virtual public hearing to testify in support of the partial decriminalization bill in Maine. A Massachusetts resident, Bell described herself as a survivor of prostitution and sex trafficking who was now the founder of an organization that helps survivors of the sex trade.

“This legislation protects survivors’ human rights over the buyers’ wants,” she testified. “I’ve been working with prostituted people for over seven years and I see the harm, the substance use disorder, the complex PTSD and the wreckage that prostitution has caused in the lives of the people we support and in my own. We’ve worked with over 400 prostituted people and we do not see liberation and freedom. We see violence and devastation.”

Even Rep. Lois Galgay Reckitt, the sponsor of the partial decriminalization bill in Maine, said she’s focused on eliminating prostitution by cutting off the demand side for sex.

“That’s the goal, is to get the incidence of prostitution to drop, frankly, to nothing,” she said.

Supporters of sex work have countered such arguments by noting research that shows partial decriminalization in other parts of the world — often referred to as the Equality Model or the Nordic Model — has still burdened people who engage in sex for money by sending them into the shadows with clients. They have noted that several organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have come out in support of full decriminalization, noting research that shows it makes sex workers more likely to report abuse and law enforcement more likely to make arrests for crimes against sex workers.

Rob Nosse, the main sponsor of the Oregon bill, spoke at the public hearing in Portland. He said he believed decriminalization of sex work and those who engage in it would lead to better public health and safety outcomes and advance the idea of less interaction in the justice system for things that consenting adults do. He thinks for the bill to pass in a future legislative session, organizers will need to build more awareness while being clear that they’re not sanctioning human trafficking for sex.

“I believe that decriminalization will help to improve the working conditions of people who do sex work. And I mean that in all seriousness,” he said. “If you think about it, we all use our bodies in our work in some form or another. Many of us, not in as intimate a way or vulnerable a manner as a sex worker, but for sure many jobs require that we bring our bodies to the work.”

Some researchers agree with the idea of full decriminalization. Alicia W. Peters is an associate professor of anthropology at the University of New England and wrote the book “Responding to Human Trafficking: Sex, Gender, and Culture in the Law.”

Peters doesn’t think enough policy ideas around partial decriminalization include resources to address root causes and social inequalities. She said policymakers sometimes do not take into account the spectrum of reasons that someone chooses sex work, including needing flexibility for child care needs and facing marginalization because of someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity.

“It leaves these opportunities for harm without actually addressing the vulnerabilities that are present in the first place because it’s approaching it through a criminal justice framework as opposed to addressing the structural issues that are in place that push people into sex work,” she said.

Bien-Aimé said a key takeaway for policymakers is to ask themselves what they want if prostitution is completely decriminalized.

“I think the overarching question is, ‘Should the sex trade actually be part of our economy, and an employer like any other employer?’” she said.

Mills, the Maine governor, said in a letter explaining her decision to veto the partial decriminalization bill that she was concerned about the repercussions of being the first state to eliminate all penalties for being paid for sex. She noted that engaging in prostitution is not a jailable offense in the state.

“I fear, will only increase demand and encourage the exploitation of young people by those who profit from the mistreatment of others, undermining the free will of those trapped in difficult and sometimes tragic circumstances,” Mills wrote.

Reckitt disagrees, and vows to reintroduce the legislation. She plans to spend more time educating the policymakers, the press and the public on partial decriminalization.

“She didn’t quite understand,” Reckitt said of Mills. “The press didn’t understand. Who did understand was the masses of survivors who signed petitions in favor of the bill, there were more than 100 of them. And so I think that the vast majority of the women who’ve engaged in this effort, or have been trafficked into it, understood exactly what I was trying to do.”

Sex workers have expressed an interest in getting a ballot initiative in Oregon that would ask voters directly whether to support full decriminalization.

At the public hearing in Oregon, Shawna Peterson, executive director of the Oregon chapter of the National Organization for Women, spoke in support of full decriminalization. She also said no matter what model or bill someone believes in, the two things everyone agrees on is that people should not be raped, kidnapped or “damaged physically mentally or in any other way.” She also said children should not be involved in any aspect of sex work. She noted that prostitution and sex work is still being debated internally at the national organization, which historically opposed it.

“I don’t believe anyone has it 100 percent perfect. But events like this are bringing us closer and closer to a second sexual revolution where everyone’s rights are intact, and everyone is safe,” she said.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect that there is a federal ban on engaging in sex for money.