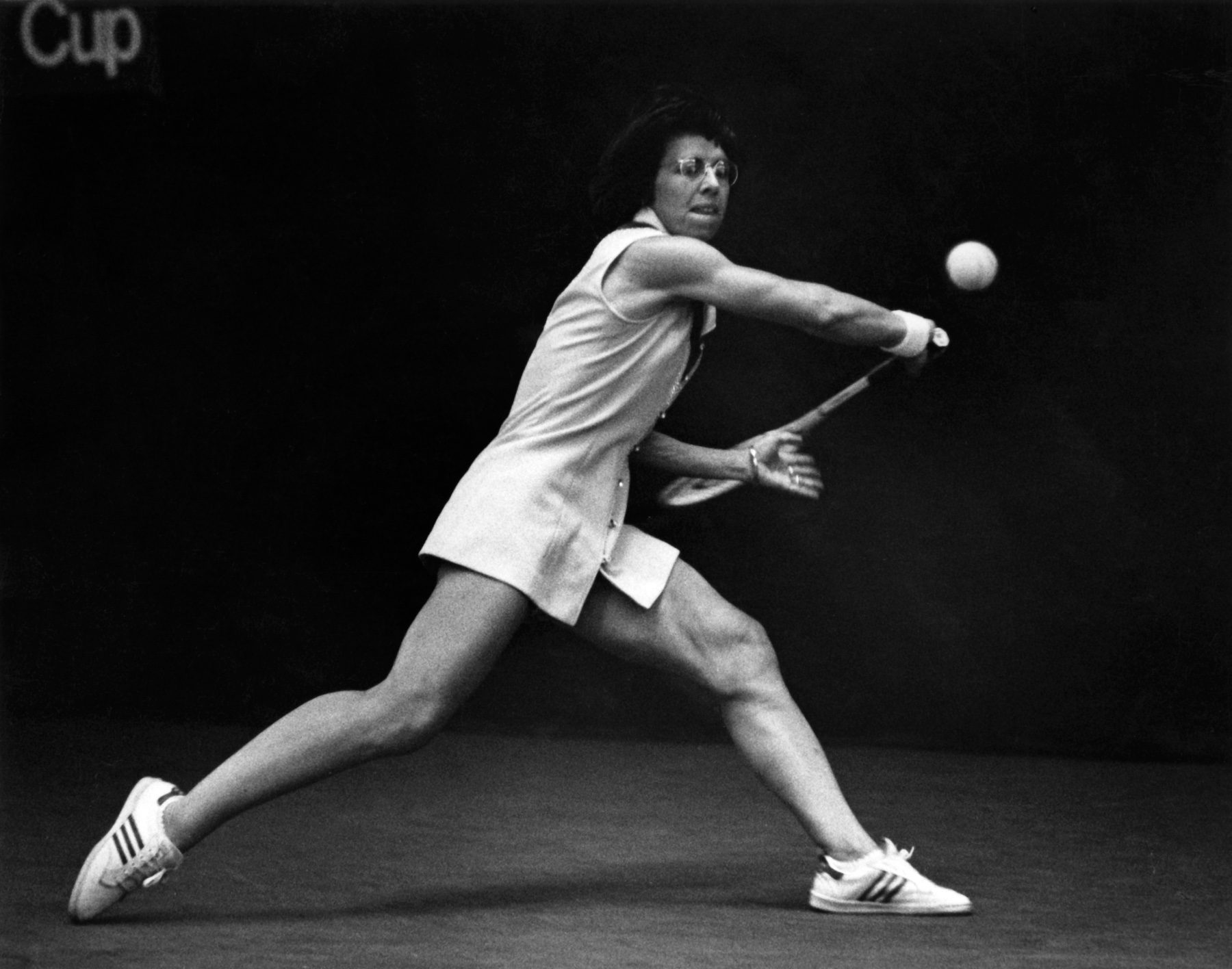

Billie Jean King made sacrifices to write her new autobiography, “All In.” In the more than four years it took to write the book, she stopped reading everything, she said at The 19th Represents Virtual Summit.

“I love reading,” she said with a sigh.

Sacrifices are nothing new to King, the tennis phenom who was perhaps the loudest and earliest advocate for pay equity in sports: She gave up a comfortable career in her 20s for the chance for women to be paid the same as men in her sport, causing ripple effects that extended far beyond tennis courts. As she reveals in “All In” and in conversation with PBS NewsHour’s Amna Nawaz for The 19th’s summit, she hopes that all of that work — for the book and in her life, both on and off court — will mean that more people can be their “authentic self.”

“I hope it will help others and enlighten others. And maybe give them some courage to take care of themselves,” King said.

King was the leader of what is now known as the “Original 9,” a group of women tennis players in the 1970s frustrated with the low pay women received. They risked expulsion to start their own professional tour. All were young and in the prime of their careers. But they came in with three clear goals in mind, King said.

One: “That any girl in this world, if she’s good enough, would finally have a place to compete.”

Two: “That she’d be appreciated for her accomplishments, not only her looks.”

And three, the “most important thing”: “To be able to make a living.”

King said those collective goals she made with the Original 9 — who together entered the International Tennis Hall of Fame last month — are why tennis is “a leader in women’s sports today.”

“Every time a woman tennis player gets a check, or makes money off the court, that is because of that moment in time that we were willing to stick together,” she said.

“All In” details some of the hardest parts of King’s career and personal life, which were often intertwined. She writes about her sexuality, and how she was “outed” as queer by a former lover without her consent. She wrote about living with an eating disorder. When recording the audio version of the book, King told The 19th that reading it all aloud was emotionally trying.

“I had to stop at times because I was crying,” she said. “And then other times it was exhilarating.”

The book, though generous and thoughtful with personal narrative, also weaves in the way her life intersected with big historical moments in the 1970s and 1980s. King, an avid student of history, recalled to The 19th that when she began playing tennis as a girl, she set about learning all she could about the history of that sport. She believes that made her an impactful advocate as she set about changing it.

King hopes that her book provides a similar backdrop.

“I think the more you know about history, the most you know about yourself,” she said. “It helps us shape the future.”