A little over a week after Nida Allam announced her bid for a North Carolina congressional seat in November, the 28-year-old shared something deeply intimate with the public: She posted a photo on social media of herself and her spouse at a doctor’s office. The post marked one year of trying to get pregnant through fertility treatments.

“It’s hard to be open about grief, infertility, and our struggles, but I know we’re not alone in this,” she wrote. “So I’m speaking up in the hopes that others feel seen, recognized, and represented.”

It’s a vulnerability that Allam — a county commissioner and the first Muslim woman elected to public office in North Carolina — has leaned into. Months earlier in August, she first posted about her fertility journey and the painful experience of having a miscarriage. She included a photo from inside a local fertility center, while in a patient gown and her hijab. She held up a peace sign.

While she has talked with local press about her fertility struggles, Allam is still trying to figure out how she wants to discuss the subject while on the campaign trail. She alludes to fertility on the campaign trail when she highlights her policy priorities.

“When I talk about what I’m fighting for on issues — when I talk about climate change, I’m saying, ‘This is personal, because me and my husband are family planning right now. And one of the factors that goes into that is, ‘Is there going to be a planet for our kids?’” she told The 19th.

There are examples of people running for office while pregnant. But Allam’s decision to campaign while also sharing details of her struggles with fertility is a rarity in American politics. She is part of a generation of young people seeking political office who are connecting their lived experiences in a time of growing inequality with their policy views, said Sara Guillermo, chief executive officer of IGNITE, an organization that helps young women prepare for political leadership.

Guillermo noted that when Stacey Abrams first ran for governor in 2018, she spoke candidly about her debt (Abrams, a Democrat, has since announced another bid). Policymakers are also using their lived experiences to talk about things like pregnancy loss.

“We’ve been doing a lot of culture-shift work in identifying the norms of why young women even engage in civic and political engagement. And I think they have this historical narrative and this definition of who a politician is, and you wouldn’t necessarily have ever talked about fertility treatments,” Guillermo said.

But Allam’s perspective as a young person was a barrier when she first expressed interest in political leadership. When she ran for an organizing position within the state party and later made her history-making bid for the Durham County Board of Commissioners, she said she was told repeatedly by others within her party to wait her turn.

“That sentiment and idea — that your voice isn’t needed at the table yet or that your voice isn’t ready to be at the table yet — is so disenfranchising when other folks don’t understand the issues that young people are dealing with right now,” she said. “We need those issues to be outspoken. We need a vocal champion to be at the table because it’s personal stories that lead to policy change.”

Allam supports a “Medicare for all” system that effectively ensures expansive health care coverage for everyone. She said that position has carried extra weight as she undergoes her fertility treatments.

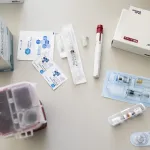

Allam said her health insurance only partially covers her current fertility treatments of intrauterine insemination (IUI), a process that involves injecting sperm directly into the uterus. Allam and her husband pay about $2,000 in out-of-pocket expenses for each cycle. She is unable to afford in vitro fertilization, or IVF: Like most insurance programs, Allam’s doesn’t cover it. Each cycle of IVF can cost on average $12,000 to $17,000 without related medication.

Allam said fertility shouldn’t be just an option for people who are either wealthy or financially comfortable.

“It really should be every individual’s basic human right. And that’s what makes it even more personal for me in this campaign — to be fighting for these issues and causes that I care about because I’m living through it every single day and we need more people who are living through these different experiences at the table,” she said.

Allam’s husband, Towqir Aziz, said he is proud of his wife for sharing such an intimate part of their lives.

“It’s inspirational for me to see her just really open up to everyone publicly like this in the hopes of normalizing the conversations around fertility and women’s health,” he said.

As a member of an all-women commission for Durham County, Allam has focused on issues like helping to fund an immigrant and refugee services coordinator position and a tax assistance grant program. She said she’s running for Congress to continue tackling issues like climate change, health care and reproductive health. Allam is vying to replace Democratic Rep. David Price, who is retiring, with the Democratic primary scheduled for the spring. The Democratic-leaning district is expected to favor a Democrat in the general.

Allam was driven to politics by loss. She was 21 years old when three of her best friends were gunned down in a hate crime in Chapel Hill that still impacts the community. The deaths of her friends — 23-year-old Deah Barakat, his wife, 21-year-old Yusor Abu-Salha, and her sister, 19-year-old Razan Abu-Salha — compelled her to get more politically involved. Shortly after, she started working on Bernie Sanders’s 2016 presidential campaign and then started leadership work for the North Carolina Democratic Party.

But running for public office didn’t mean putting another dream, parenthood, on hold.

“For me, it’s something that is a very emotional and difficult process to go through. Especially month after month, going through the emotional pain and weight of these doctor’s appointments. Constantly being tested, to have a negative pregnancy test after negative pregnancy test,” she said. “To put a pause on that feels as if I was giving up on hope. And for me I did not want to give up on that hope.”

Allam was inspired by Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, who in 2018 became the first U.S. senator to give birth while serving in office. Duckworth made history when she later brought her newborn daughter onto the chamber floor for a vote.

“When talking about your birthing plan, talking about being a mother, talking about being a parent, it is always something that has unfortunately been considered a weakness or has been used against individuals and their viability for office — it does show a great strength to be able to be a parent of a young child, bringing them to the floor, balancing that part of your life,” she said.

Still, there wasn’t a blueprint for dealing with fertility issues while running for office. While most of the responses to Allam’s fertility journey have been positive and supportive, Allam said she was cornered recently by a woman at a political event who started yelling at her about her miscarriage, accusing her of sharing her story for political gain. Allam called the experience, which happened before she announced her congressional bid, painful.

“I was very upset by it,” she said. “But it also reminded me that there are young girls and young birthing people who will be approached by someone like that, who we need to counteract that narrative with conversations of love and acceptance and support.”

Allam said sharing her story has prompted other Muslim women to reach out to her about their fertility journeys. She serves on the board of directors for Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, the organization’s umbrella for North Carolina and surrounding states.

Lela Ali is the Muslim organizing program specialist at Planned Parenthood and the policy director for Muslim Women For, a North Carolina-based organization that advocates for Muslim women. Her organization, and others in the area, have worked with Planned Parenthood on programs aimed at destigamatizing conversations within the Muslim community about reproductive health through education and advocacy.

Ali said having a Muslim leader like Allam be public about fertility is empowering for people who face barriers within different facets of reproductive health care, whether they’re Muslim or not. But she noted that Muslim women and nonbinary people are among those most at risk.

“There’s stigma around conversations around sexual reproductive health. There’s stigma around conversations about abortion, about fertility issues,” she said. “This stigma can be really dangerous and painful and hurtful and harmful … it maintains and protects those barriers that are designed to make people not have the access that they need.”

Dr. Noor Al-Shibli, Allam’s OB-GYN, said she works with patients who only confide in a small group of people about their struggles with infertility.

“They feel secure in sharing and I think a lot of that has to do with the social stigma and expectations that we have surrounding pregnancy and motherhood,” she said. “I think the fact that more and more folks are becoming vocal about this publicly is really great, because it can really remind people going through this journey that they’re not alone.”

Allam hopes she is creating a space to talk about reproductive health, not just from a policy standpoint but on a personal level.

“It’s not necessarily just even fertility. I’m just having conversations more openly and honestly, and giving some women and some people a space to have those deeper dive conversations about how to advocate for themselves, how to advocate for their bodies and their health, with their doctors, with their families and their spouses,” she said. “I think that’s so important within the Muslim community, but within the broader community as well.”