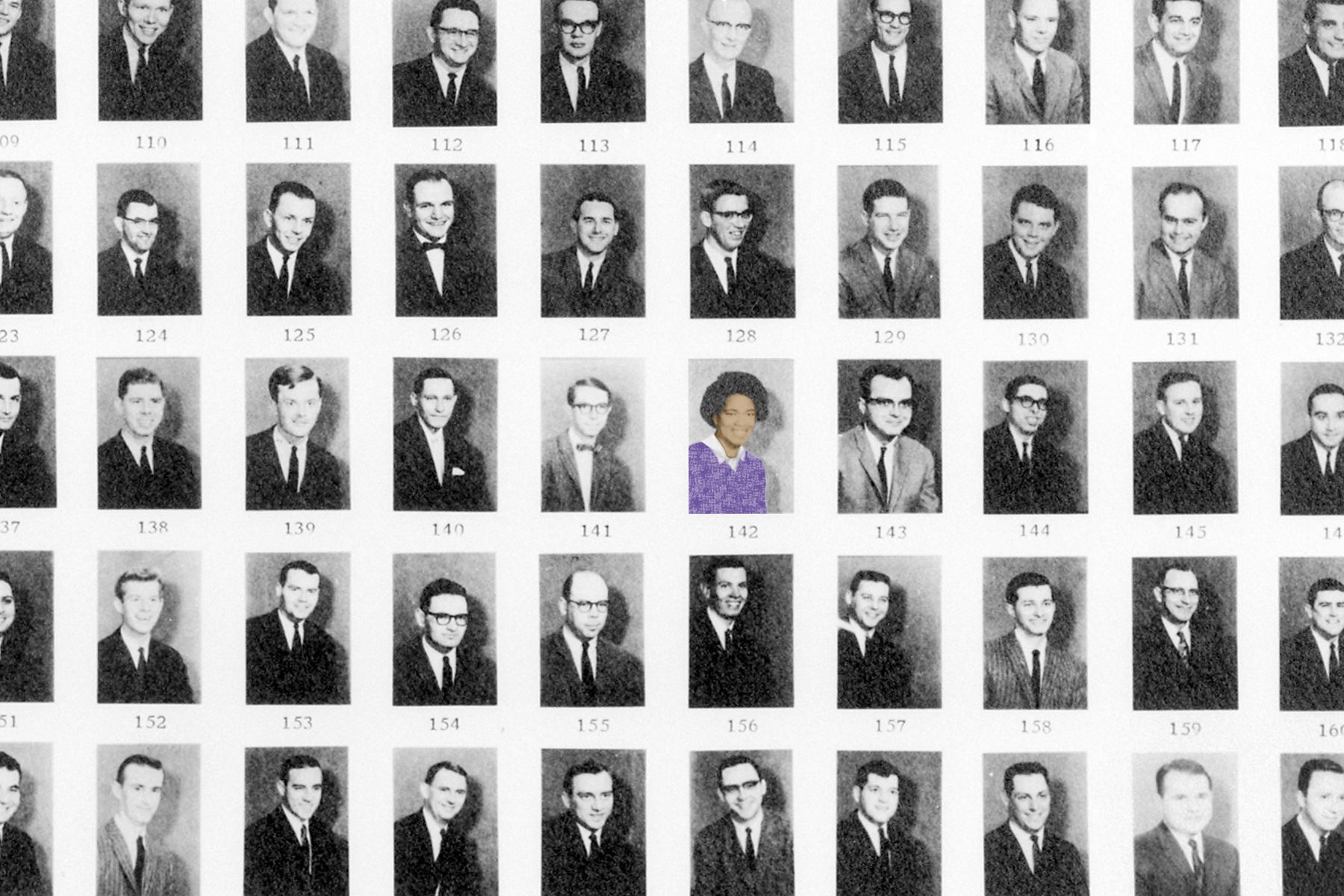

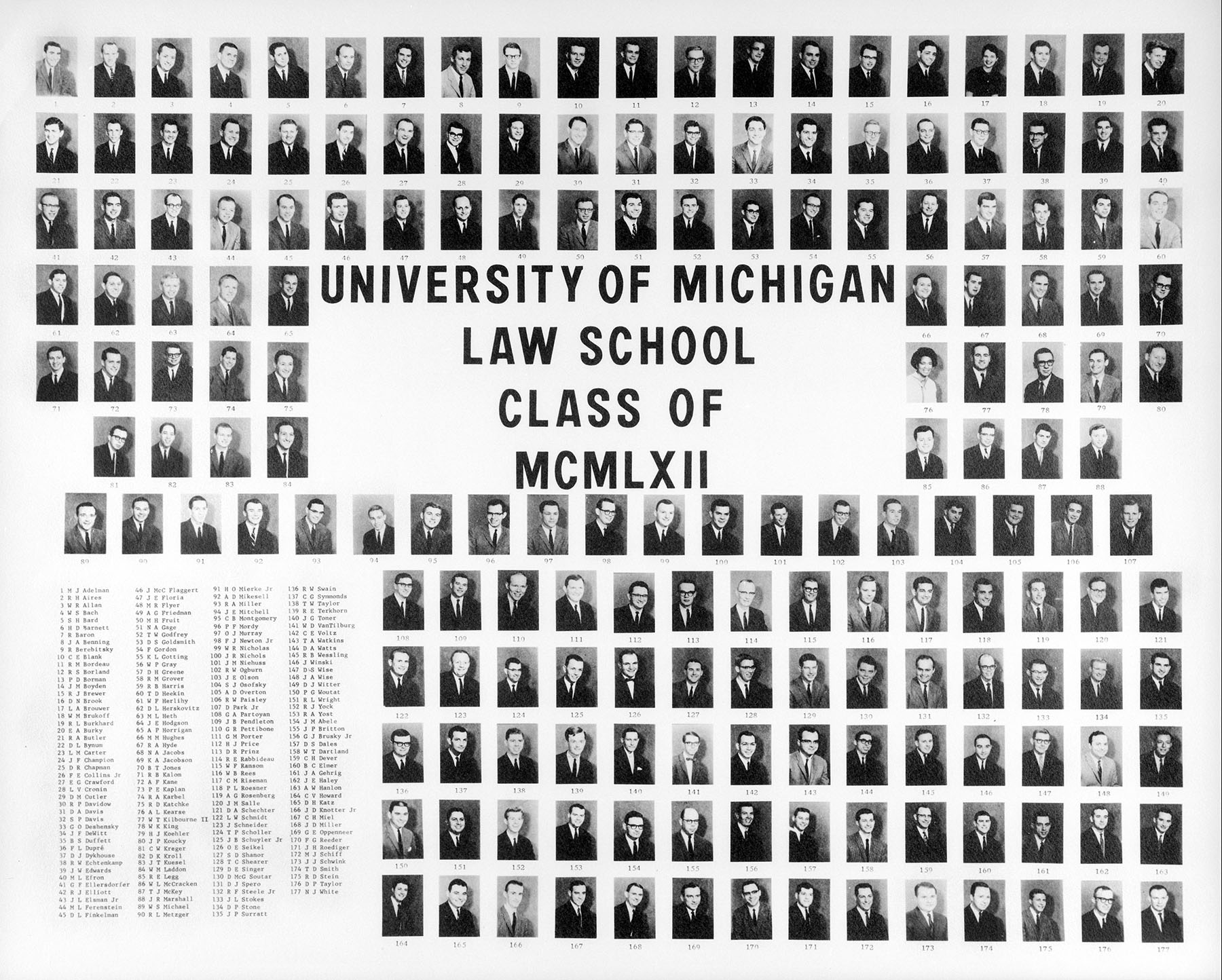

On its website, the University of Michigan has an image of the Law School Class of 1962. It’s a sea of White men, smartly dressed in suits and ties. But five rows down, on the right, is Amalya Lyle Kearse, the only Black woman in the class — who would go on to make history on more than one occasion.

As the country prepares to watch the confirmation process for the first Black woman nominated to the nation’s highest court, The 19th revisits Kearse, who was the first Black woman judge on an appellate court and who still sits on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit. She was considered for a Supreme Court nomination by three different presidents, the first Black woman on record to receive such recognition. Kearse was a key figure in paving the way for Black women judges, who even with the high-profile nomination of Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court are underrepresented on the U.S. judiciary.

“Amalya Kearse’s existence on President Reagan’s shortlist over 40 years ago is concrete evidence that for as long as women have been allowed to be on the Supreme Court, there have been Black women who have been qualified to be there, and it is a long time coming to finally have that fulfilled,” said Renee Knake Jefferson, a professor at the University of Houston Law Center and co-author of the book “Shortlisted: Women in the Shadows of the Supreme Court.”

Kearse was born in 1937 in the predominantly Black town of Vauxhall, New Jersey, about 20 miles outside of New York City. She rarely speaks to the press — Kearse declined to be interviewed for this article — but she did talk about her life and career with NPR in 1979. In that interview, Kearse told NPR that she and her brother were encouraged to achieve from a young age.

“We were always being asked what we wanted to be when we grew up,” Kearse said at the time. “I found that was something of a difference between me and some of the women that I went to school with, some of whom had no thoughts of a career at all, and weren’t at all encouraged to have thoughts of a career.”

-

More from The 19th on the Supreme Court nomination

- Four Black women became classmates, roommates and lifelong sisters. One of them is now a historic nominee for the Supreme Court.

- History made: Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson to be first Black woman nominated to the Supreme Court

- How Ketanji Brown Jackson’s pursuit of success as a lawyer and parent got her a Supreme Court nomination

She was reportedly one of three Black students in her freshman class at Wellesley College, where she received her bachelor’s degree; she was also the only Black woman in her law school class at the University of Michigan.

In the few interviews Kearse has done, she did not talk about specific barriers in her life as a result of her race, but she did observe some challenges when it came to gender.

“When I was in law school and looking for a job, I knew I wanted to be a litigator, and I wanted to go to Wall Street. And when I started interviewing, I talked to a lot of firms that had no women at all, and I don’t believe I talked to a single firm that had any women in their litigation departments,” Kearse said to NPR.

But she was not deterred. Kearse said she considered Wall Street “the big leagues” and wanted to see if she could do the job. After law school graduation, she went to work for Hughes Hubbard & Reed, a top Wall Street law firm where she became the firm’s first woman and first Black partner seven years later. As a litigator, she handled antitrust, banking, commercial and product liability cases. She argued and won Broadcast Music Inc. v. Columbia Broadcasting System Inc. before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1979, an antitrust case that sought to settle whether a particular licensing agreement for copyrighted music constituted illegal price fixing.

“She is a very strong legal analyst with strong writing skills. She was a very important influence on my development as a lawyer,” George Davidson, senior counsel at Hughes Hubbard & Reed, told The 19th.

When he learned that President Jimmy Carter, a Democrat, was considering her for a prestigious judicial appointment on a federal appellate court, he was not surprised. “I told her she was going to get it,” Davidson recalled. “She really is ideally equipped for that position.”

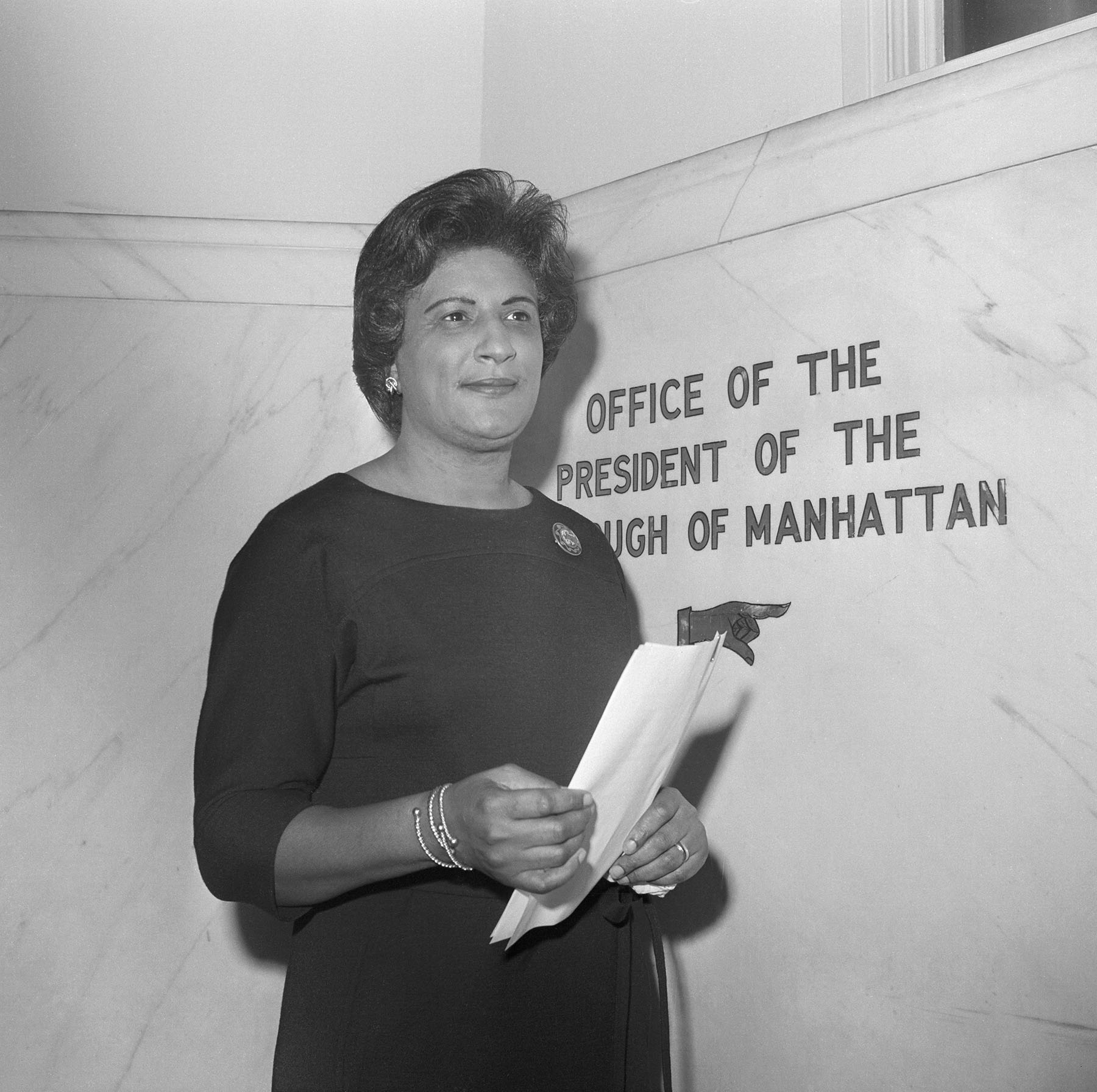

Kearse had served on Carter’s judicial nominating commission, formed to recommend candidates for circuit court vacancies, a role that probably helped her catch the president’s attention, Jefferson said. By the time Carter nominated Kearse to be a judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit in June 1979, she had already been recruited to be an assistant U.S. attorney general and to be a federal district judge in New York. But she had turned down those opportunities. She wanted to be a judge at the appellate level.

During her Senate confirmation hearings for the 2nd Circuit, New York Sen. Jacob Javits, a Republican, sang her praises. “I can only give her the best recommendation of any that I know of,” Javits said during the 1979 hearing. “Some four to five years ago, I offered her a district court judgeship. She then said she thought her talents and experience needed to be more matured and that she hoped ultimately to go on the bench, but she hoped she would be appointed to an appellate court. Here she is, her talents matured and her appointment before the Senate.”

Kearse was confirmed to the 2nd Circuit, making her the first Black woman appellate judge and, at age 42, the second-youngest person at the time to sit on a federal appellate court. She was also the first woman and the second Black judge on the 2nd Circuit, following Thurgood Marshall, who had become the country’s first Black Supreme Court justice.

Kearse was one of several Black women to break barriers at multiple levels of the judicial system. Jane Bolin became the first Black women judge in the country in 1939; Constance Baker Motley — who shares a birthday with Jackson, as the newest Supreme Court nominee pointed out last week — became the first Black woman federal judge in 1966. Nine years after Kearse made history, Juanita Kidd Stout became the first Black woman to serve as a state Supreme Court justice, serving in Pennsylvania.

Though Kearse broke through a significant barrier, she did not speak much publicly about herself within that historic context, said Angela C. Robinson, a retired Connecticut superior court judge and author of “First Black Women Judges: The Story of Three Black Women Judges in the United States.”

“On the one hand, it’s very clear that she has a strong and secure identity as a Black woman. On the other hand, she rarely talked about race,” Robinson said.

Kearse is a member of the country’s first Black sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, and served on the national board of the NAACP, but her relative silence on race and civil rights issues raised eyebrows from some Black lawyers at the time, reports indicate.

“I haven’t really been enormously active in any causes,” Kearse said to NPR in 1979. “I have been involved, to some extent, in a lot of different activities, and have been on a number of boards, including boards of organizations that are heavily involved in civil rights activities. But I have not been that active really in any movement, but I don’t know that that should make anyone suspicious of my ability to be a good judge.”

Despite Kearse’s low-key national presence, she garnered interest from both Republican and Democratic presidents. She was considered on two separate occasions by President Ronald Reagan. She was within reach of becoming the first woman justice on the Supreme Court in 1981, but Reagan selected Sandra Day O’Connor for that historic title. Kearse was also considered for vacancies on the high court by Presidents George H.W. Bush, a Republican, and Bill Clinton, a Democrat. Jefferson of the University of Houston Law Center said her research did not reveal a specific reason Kearse never ultimately received a Supreme Court nomination. She and Robinson also noted the significance of Kearse’s wide bipartisan appeal.

“Republicans and Democrats respected her intellect and really felt she was neutral enough that they seriously considered her as a contender,” Robinson said.

People remember Kearse being mostly about her work, though she was known to be a talented recreational tennis player and a championship-winning bridge player. She has kept her life largely private and does not seek out external publicity or accolades. Today, Kearse is 84 years old and a senior judge on the 2nd Circuit, meaning she hears a reduced number of cases.

Clerks who have worked for her told The 19th that she was a boss with high expectations who also cared about supporting young lawyers.

“She was particularly exacting and demanding and that meant learning a lot, but it also meant working extremely hard,” said Maria Foscarinis, the founder of the National Homelessness Law Center, who clerked for Kearse from 1981 to 1982. “She has always been such a brilliant jurist and legal mind. I learned a tremendous amount from her.”

Public interest lawyer Esha Bhandari, who clerked for Kearse from 2010 to 2011, echoed that sentiment. “She just gets on with it. She worked harder than her clerks and set that example for all of us, but she was never going to ask us to push ourselves or work harder than she was willing to do herself,” Bhandari said.

Those who know her or have researched her say her influence on the federal judiciary and conversations about Black women on the Supreme Court is particularly prescient at this moment in U.S. history.

“She never sought the limelight,” said attorney Karin Portlock, of the law firm of Gibson Dunn, who clerked for Kearse in 2008. “But she is a phenomenal jurist, who has quietly blazed a trail for Black women in this profession. It is awe-inspiring what she has accomplished.”