Since taking office, President Joe Biden has forgiven more than $18.5 billion in student loan debt for select groups and repeatedly extended a pandemic payment pause. But he’s expected to soon take a bigger step on student debt and use executive authority to broadly forgive some debt for millions of borrowers.

It’s still not clear how much of the $1.7 trillion in debt will be canceled, but the administration is reportedly considering forgiving $10,000 for individual borrowers who make less than $125,000 to $150,000 a year. Many progressive lawmakers and advocates are calling for even more, arguing that Biden should forgive up to $50,000 of student loan debt per borrower and take steps to reduce or waive college tuition.

A spokesperson for the Department of Education said the administration is looking at the issue of college affordability but did not say how. Its review of broad-based debt cancellation is ongoing.

Many conservative lawmakers, however, oppose expanded loan forgiveness. A group of Republicans, led by Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah, has introduced legislation called the Student Loan Accountability Act, which would prevent Biden from canceling any student loans that don’t already qualify under existing programs or authorizing any department in the federal government to do so.

-

More from The 19th

- In Texas prisons, men have access to significantly more higher education programs than women

- Adjunct professors, the ‘backbone’ of higher education, push for better wages and benefits

- House progressives urge Biden to support caregiving workforce and execute other Build Back Better priorities

Two-thirds of Americans favor at least some debt relief for people who hold student loans, according to a May YouGov poll. Roughly half of Americans support a minimum of $25,000 in forgiveness. In 2020, individual student loan balances reached an average record high of $38,792, according to Experian, the consumer credit reporting company. Canceling $50,000 of student debt would completely eliminate the balances of about 80 percent of borrowers. Forgiving $10,000 would leave about a third of borrowers with no balance.

Women borrowers could particularly use the relief. They are more likely than men to go to college, more likely to get advanced degrees — and more likely to have student debt and be paid less when they graduate. They hold two-thirds of all student loan debt, and the burden is greater for women of color. Earning an advanced degree worsens the problem: A year after finishing graduate school, Hispanic and White women owe on average just over $56,000, Native American women owe nearly $62,000, Asian American women owe almost $71,000, and Black women owe over $75,000.

Georgetown University researchers have found that graduate school does not improve the wage gap for women, who earn 81 percent of what men make overall. That’s because women typically pursue advanced degrees in fields such as education, health administration and social work, which do not pay as well as fields more men typically pursue, such as engineering, finance and medicine.

The 19th wanted to speak to women who have student loans, particularly people who have borrowed for graduate school. Five women spoke about their life with student debt and what it’s like to carry that burden even years after earning degrees.

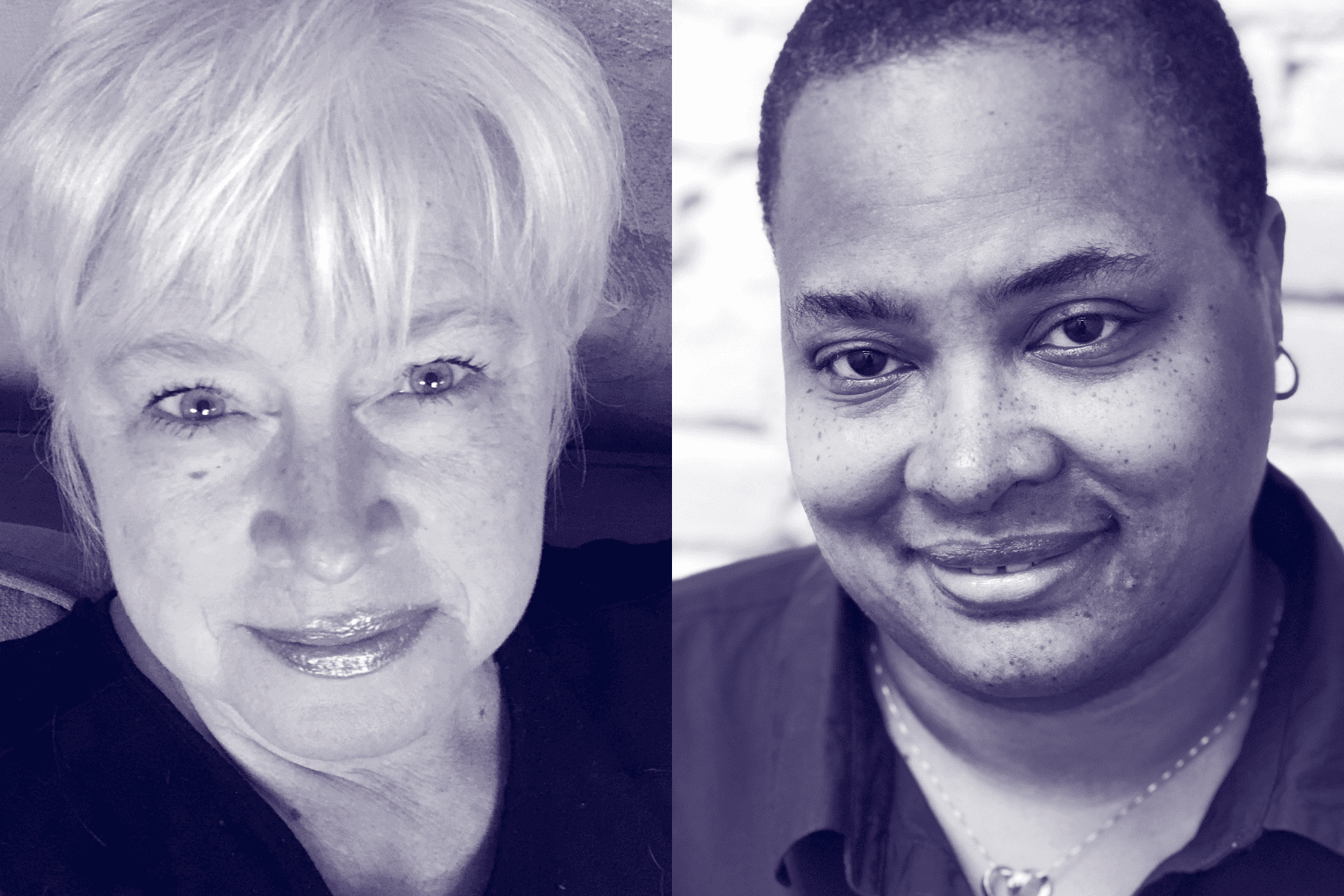

Michelle Dennis

Age: 45

Amount owed: About $100,000

Job: Dean of Nursing and Allied Health at Baton Rouge Community College

Raised by a divorced mother of two who earned a meager salary as a leasing property officer, Michelle Dennis knew as a teenager growing up in Mobile, Alabama, that she would have to find ways to fund her college education. “I worked really hard in high school to make sure that I had good grades so that I could get some scholarships,” Dennis said.

In 1998, she graduated from Xavier University of Louisiana with little student loan debt, thanks to scholarships and the Pell Grant, which the federal government awards to students based on financial need. But when Dennis returned to school to get a second bachelor’s degree in nursing from the University of Alabama, she relied largely on student loans. Then, she completed a master’s degree in health care administration in 2014 and a doctorate in health care public policy in 2019, both from Southern University and A&M College in Louisiana. She now owes about $100,000 in student loans, and her salary is not enough to easily pay back what she owes, she said.

During the pandemic, Dennis has taken advantage of the pandemic payment pause. She also has applied for the public service loan forgiveness program, which is designed to help borrowers in professions such as nursing, teaching, the military and the government. The vast majority of borrowers who apply for the program are denied: The Education Department said it rejected 98 percent of borrowers who applied for the program from fall 2020 to spring 2021. The Biden administration has recently made changes to this program so that more borrowers qualify. In March, it announced that it would eliminate the debt of 100,000 people through public service loan forgiveness. Dennis is hopeful she will qualify.

“I work in the community college system, so I’m working in an industry where I’m giving back,” Dennis said. “I’ve always worked, even as a bedside nurse and a hospital administrator, in state hospitals. So, I was still working for a government entity, and I feel like that should count for something.”

Emily Escobar

Age: 25

Amount owed: $12,000

Job: Campaigns and organizing associate for Civic Nation; graduate student

When Emily Escobar earned a bachelor’s degree in 2018 from California State University, Long Beach, she became the first person in her family to graduate from college. Having immigrated to the United States from Guatemala at age 3, she grew up seeing a college degree as the American dream. To realize that dream, one that her housekeeper mother always had for her, Escobar worked during college. Her wages, however, were not enough to fully pay for her tuition.

“Because of my family’s income, I was able to receive financial aid,” she said. “But it wasn’t enough to cover all of the costs that I needed, so I decided that student loans would be my best option.”

Now a campaigns and organizing associate for Civic Nation, an organization focused on issues including civic engagement, social justice and voter participation, Escobar has $12,000 in student loan debt. If Biden were to offer $10,000 in loan relief, most of her debt would be eliminated and her quality of life would improve, she said. She struggles to make ends meet. She and her boyfriend live with his family, and she drives a 16-year-old car.

“Situations come up where my car breaks down or I had an incident recently where I had to go to the hospital,” she said. “So, I’ve never really been able to save enough to buy a new car or rent a place of my own.”

She’s also in school, pursuing a master’s degree in applied gender studies at Claremont Graduate University. Escobar has not made student loan payments during the pandemic pause. Instead, she’s been putting that money toward her graduate school tuition, which, so far, she has not taken out student loans to cover.

After grad school, Escobar wants to put her degree to use in the nonprofit sector. “My mom’s goal was always to get me into college because she knew that would help get me out of poverty.”

Elizabeth Delancy

Age: 52

Amount owed: About $80,000

Job: Associate professor and program coordinator of dance at Albany State University

Thanks to a mother capable of covering her undergraduate tuition, Elizabeth Delancy did not take on student loans for her bachelor’s degree from Hampton University.

“My mother really did give my brother and me a head start,” said Delancy, who graduated in 1991.

Seven years later, Delancy earned a master of fine arts. She followed that up in 2007 with a doctorate in humanities, both from Florida State University. She took out student loans to pay for graduate school but planned to repay her debt after earning her PhD in humanities. Today, though, Delancy hasn’t made much of a dent in her debt because her income isn’t high enough, she said. She owes about $80,000.

Now an associate professor and program coordinator of dance at Albany State University in Georgia, Delancy is part of the public service loan forgiveness program — but the government doesn’t count the years she worked as an adjunct, she said, and her loans have yet to be eliminated. If she were debt-free, she would pursue homeownership.

She said she would qualify if Biden provides income-based loan relief but said $10,000 in forgiveness would not change her financial predicament.

“I don’t see, with what I make, the ability to really pay these off because the interest alone keeps me chasing my tail,” she said. “I can’t even get to the principal, so if they removed the interest, then I could see a light at the end of the tunnel, but $10,000 in loan forgiveness, what does that do for me? Absolutely nothing.”

Vanji Unruh

Age: 59

Amount owed: About $132,000

Job: Child welfare attorney

As Vanji Unruh approaches retirement, she has come to a startling realization about her adulthood.

“I have not had a year in my adult life ever without student loans,” she said.

Her loans date back to the 1980s, where she took on debt to pay for college at a private institution before transferring to a less expensive public one. The third of six children in a Northwest Minnesota household, Unruh could not turn to her parents to pay her tuition.

Now a child welfare attorney living in Exeter, California, Unruh owes approximately $132,000 in student loans, many times more than the $26,000 she borrowed 40 years ago to pursue a bachelor’s degree, she said. Biden canceling $10,000 in student loan debt would do little for her, Unruh said.

“If $10,000 is taken off, it’ll just be another 10 months and that $10,000 will be right back on” with interest, she said. “Really, what I’d like to see is him cancel it all.”

Unruh has applied for public service loan forgiveness, but the federal government has only counted the time she spent as a full-time employee and not as a contractor. Unruh said that she’s encountered “a never-ending cycle of restarting timelines and interest that make my student loan balances keep going up.”

Her loans have prevented her from having a robust emergency fund or planning for retirement, she said. Although she’s an attorney, she’s not a wealthy one.

She persuaded her daughter, who she raised as a single parent and is now completing a master’s degree at Sacramento State University, not to use student loans. Unruh is active in an organization called Student Loan Justice and does not believe that the nation’s student loan debt crisis is the fault of borrowers.

“I have more than multiple times paid off my loan, and they still say I owe,” she said. “This is not about borrowers; it is about a bad lending system.”

Bummi Anderson

Age: 50

Amount owed: More than $50,000

Job: English professor

Bummi Anderson and her twin sister were the first in their nuclear family to earn bachelor’s degrees. It was the early 1990s, and she went to a state school in Georgia. Her financial aid package, which included Pell Grants, covered most of her tuition.

But her master’s degree was a different story. After completing her master’s degree in English and creative writing from Southern New Hampshire University in 2014, her debt soared. She would not say how much she owes today but said that it is well over $50,000. She’s not enthusiastic about Biden potentially forgiving $10,000 in debt.

That amount of relief “wouldn’t put a dent in my student loans,” said Anderson, now an English professor. Without government intervention of some kind, the 50-year-old expects to die with her debt. She thinks the government should provide more relief.

“Certainly, that would help out most minorities,” she said. “And we know that minorities have more debt than anybody else.”