Growing up, Atiyah Harmon always gravitated toward math. In elementary school, she developed a knack for the subject, participating in citywide math competitions in her native Philadelphia.

By high school, however, her interest in the subject had started to wane.

“I didn’t have really good teachers,” she said. “So, I kind of backed away from it. My senior year I could have been in honors math and I chose not to be.”

What pains her in retrospect is that no one urged her to take the higher-level math class. As founder of Black Girls Love Math, Harmon wants Black girls to have the opposite experience today. She rediscovered her enjoyment of math while tutoring students and decided to become a math teacher, achieving that goal in 2005.

“I noticed around sixth grade the girls were still super excited to know the math, and around seventh or eighth, they would kind of veer away,” she said. “It was just like, ‘This is interesting. What’s going on here?’”

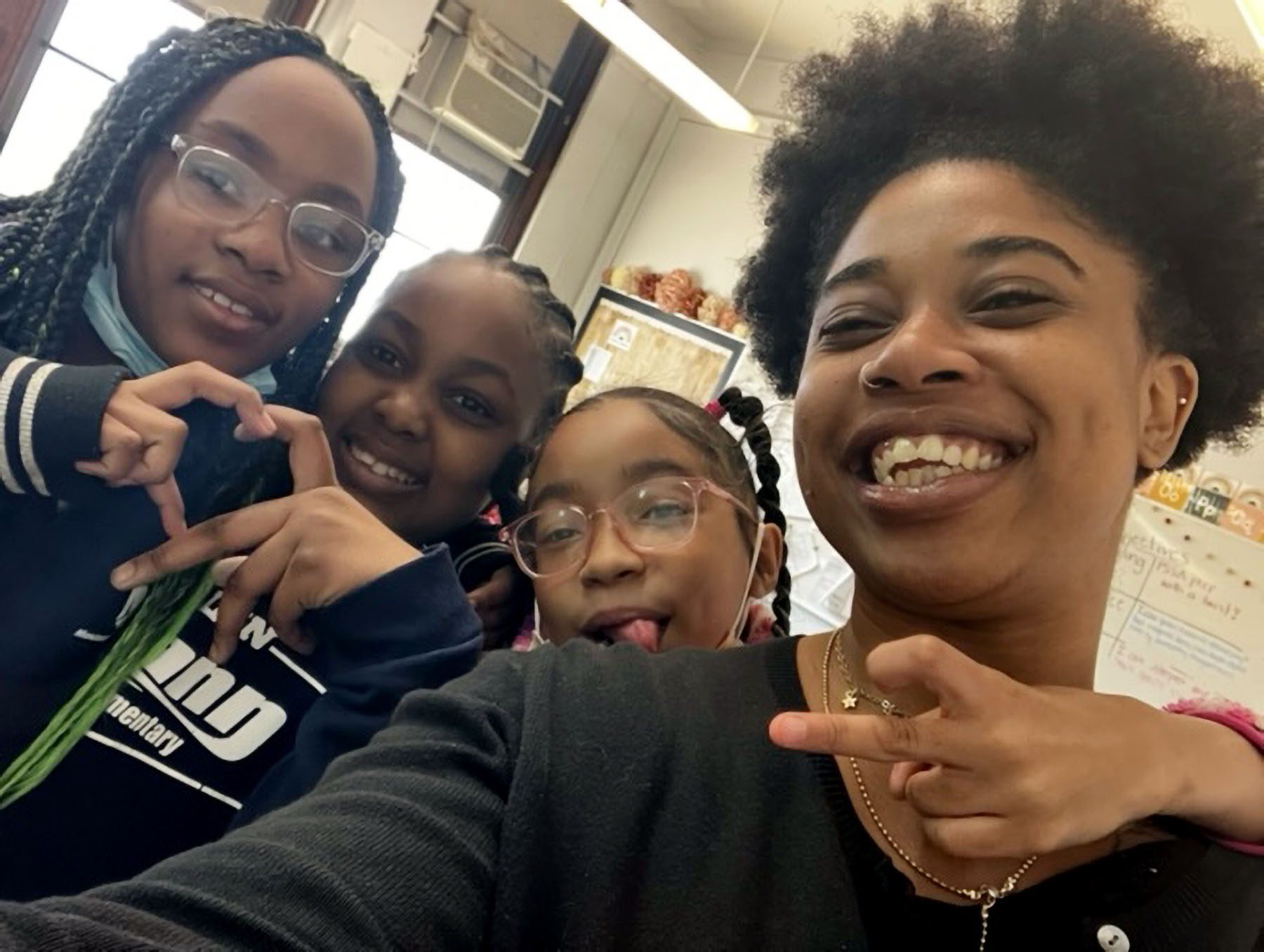

A friend suggested that Harmon take action to address the issue, and she launched Black Girls Love Math in 2020. The organization aims to foster a fun and encouraging learning environment through which Black girls in grades K-12 can develop the confidence to explore mathematical concepts, participate in cooperative competitions, and receive mentoring and other services in a culturally responsive manner. Up to 300 girls from Philadelphia-area schools take part in the program, repeating affirmations and celebrating “She-roes” — prominent Black women in math — during sessions.

Although Black Girls Love Math is a new organization, it’s part of a 21st-century movement across the country to foster Black girls’ interest in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) subjects, an area where girls and women of all racial backgrounds have long been underrepresented. Efforts such as Girls Who Code, I Am STEM and Girls STEM Institute, which predate Black Girls Love Math, share a similar mission to inspire Black girls and other marginalized youth to fulfill their potential in math and science.

Just 2.9 percent of Black women earn STEM degrees, and research indicates the problem starts well before college graduation. A 2021 study found that educators are less likely to recommend Black girls for advanced placement calculus, even when their academic records are similar to students enrolled in such classes. When Black girls overcome the hurdles they face in high school and college to enter a STEM profession, they often encounter pay disparities. Black and Hispanic women in STEM earn a median annual salary of $57,000, significantly less than White and Asian women and men of any race, according to the Pew Research Center.

One of the benefits of math and science enrichment for Black girls, the founders of these programs say, is that participants learn to have faith in their academic prowess and their worthiness as individuals.

Lauren Shepherd, 8, has been involved in Black Girls Love Math since last year. She has enjoyed learning about Black women mathematicians such as Mary Jackson, depicted in the 2016 film “Hidden Figures.”

Math is Lauren’s favorite subject in school because she enjoys learning how numbers make things work, she said. But she also appreciates the math enrichment she receives in Black Girls Love Math.

“It is not like you’re doing the same thing in school,” she said. “You get to do games while you’re learning.”

LaShaya Duval-Shepherd is Lauren’s mother and also the head of Philadelphia’s Belmont Charter High School. She said math enrichment gives children a break from the drills commonly assigned in math class and can help them enhance their skills and become active learners.

“It’s OK to be wrong,” she said. “It’s OK to figure out things and not always know [the answers]…, to just stick with it and feel passionate if there’s something that you have an interest in.”

She wanted her daughter to take part in Black Girls Love Math so Lauren could interact with Black women in STEM and discover that studying math can prepare one for a variety of fields.

As an educator, Duval-Shepherd has seen too many girls shy away from math as they reach high school. She wants Lauren to have a different outcome.

“She always had an affinity toward math,” Duval-Shepherd said. “I thought it was important that she continued to see math as something that she was good at and that gave her confidence.”

Gina Cappelletti, assistant principal of instruction at the Mann Campus of Mastery Charter Schools in Philadelphia, brought Black Girls Love Math to her school for similar reasons. Her student body is nearly all Black, and she wanted the girls there in particular to believe that they could excel in math. Marginalized students are vulnerable to a phenomenon known as stereotype threat in which they hear the negative stereotypes about their demographic, such as “Black girls aren’t good in math,” and perform poorly when tested on that subject as a result.

“We know from research that math anxiety is real; stereotype threat is real,” Cappelletti said. “So, consistently girls, and even more so Black girls, are told what they’re good at, what they’re not good at, how they can participate, where they can participate. And, oftentimes, those things exclude them from mathematics.”

Math enrichment programs like Black Girls Love Math create a safe space for students to build confidence with the encouragement of others, Cappelletti added. She said that leads to a shift in mindset that she has observed in her students, several of whom did not consider themselves to be good at math before participating in the program. Cappelletti said Black Girls Love Math also helped their academic performance: Class participation increased, and they were more willing to problem solve and take risks than they had been before.

She credits these improvements to the relationships that the girls formed with the program’s teachers, Black women who work in mathematics or related fields.

“We know that the teacher in the room makes a difference, right?” Cappelletti asked. “If students see that role model and know that someone believes in them, those things lead to academic gains. The [Black Girls Love Math] teachers were just incredibly supportive and encouraging, and the girls were able to have a role model and feel comfortable working on their math skills.”

Harmon eventually wants to scale the program, branching out to Brooklyn and Harlem in New York, and then across the country, and possibly around the world, she said.

Outside Philadelphia, programs such as I Am STEM and Girls STEM Institute are also providing math and science enrichment for Black girls. In 2017, Natalie S. King, assistant professor of science education at Georgia State University, started her two-month-long I Am STEM enrichment summer camps in the Atlanta metro area. The camps serve about 500 youth, largely Black girls.

“A lot of times in our schools, science is basically memorization and regurgitation of information, and that’s not what we want them to do,” King said. “We want them to engage in critical thinking. We want them to learn how to communicate their knowledge and be able to collaborate with other individuals because science does not happen by yourself. It happens in collaboration with other scientists.”

King also wants the students in her program to think of themselves as brilliant and gifted and to develop their creativity, inquisitiveness and sense of purpose.

“The more that we can affirm and validate them, the better off they can be when they go out back into their schools or back into their communities,” she said.

At the Girls STEM Institute, founded by Crystal Morton, an associate professor of mathematics education at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis, students receive math and science enrichment during the summers and on Saturdays throughout the year. In the program, girls learn to apply math and science to real-world situations.

Demetrice Smith-Mutegi, the program’s director of science engagement and research collaborator, said students learn to connect financial literacy to math standards. They also use math to explore issues such as the role of interest rates in housing discrimination or the demographics of groups receiving vaccines, said Smith-Mutegi, an assistant professor in the Darden College of Education & Professional Studies at Old Dominion University.

“Classrooms need to be humanizing,” said Smith-Mutegi, who co-authored a recent study with Morton on the impact of Girls STEM Institute. They found that participants developed higher levels of self-efficacy, or the “confidence that one can achieve a goal.”

“Classrooms need to be spaces where they can engage in authentic math and science experiences, where they can apply their day-to-day living to solving problems and working collaboratively and really just thinking about how to enjoy what they’re learning, essentially,” Smith-Mutegi said.

Girls STEM Institute also involves the families of students in the learning process, a move that schools don’t always make, Smith-Mutegi said. The youth in the program not only feel more comfortable about their math and science abilities after participating but also are engaged enough in their education to advocate for themselves back in their classrooms. They’re learning to speak up when they need support rather than sit back and stay quiet, Smith-Mutegi said.

Self-advocacy is a skill that Harmon wishes she had when she opted out of honors math her senior year. Through Black Girls Love Math, she hopes to affirm her students to such a degree that they stand up for themselves when others have low expectations for them and don’t encourage them to reach their academic potential.

Ultimately, Harmon intends to counter harmful narratives about Black girls and mathematics. The program is especially affirming for Black girls who enjoy math and don’t want to feel like the odd one out for their interest in the subject, Harmon said.

“It’s safe to embrace your love of math in this community,” she said.