For most of her career, reproductive endocrinologist Dr. Stephanie Gustin and doctors like her have been told to set their politics, religion and beliefs aside when practicing medicine. They’ve rarely stepped into the abortion debate.

The day Roe v. Wade was overturned changed that — likely forever. Since late June, fertility doctors have built coalitions and political committees and lobbied their state legislators, using their positions in a way they never have to serve as a bridge for conversations about reproductive health with politicians who support fertility care — but not abortion.

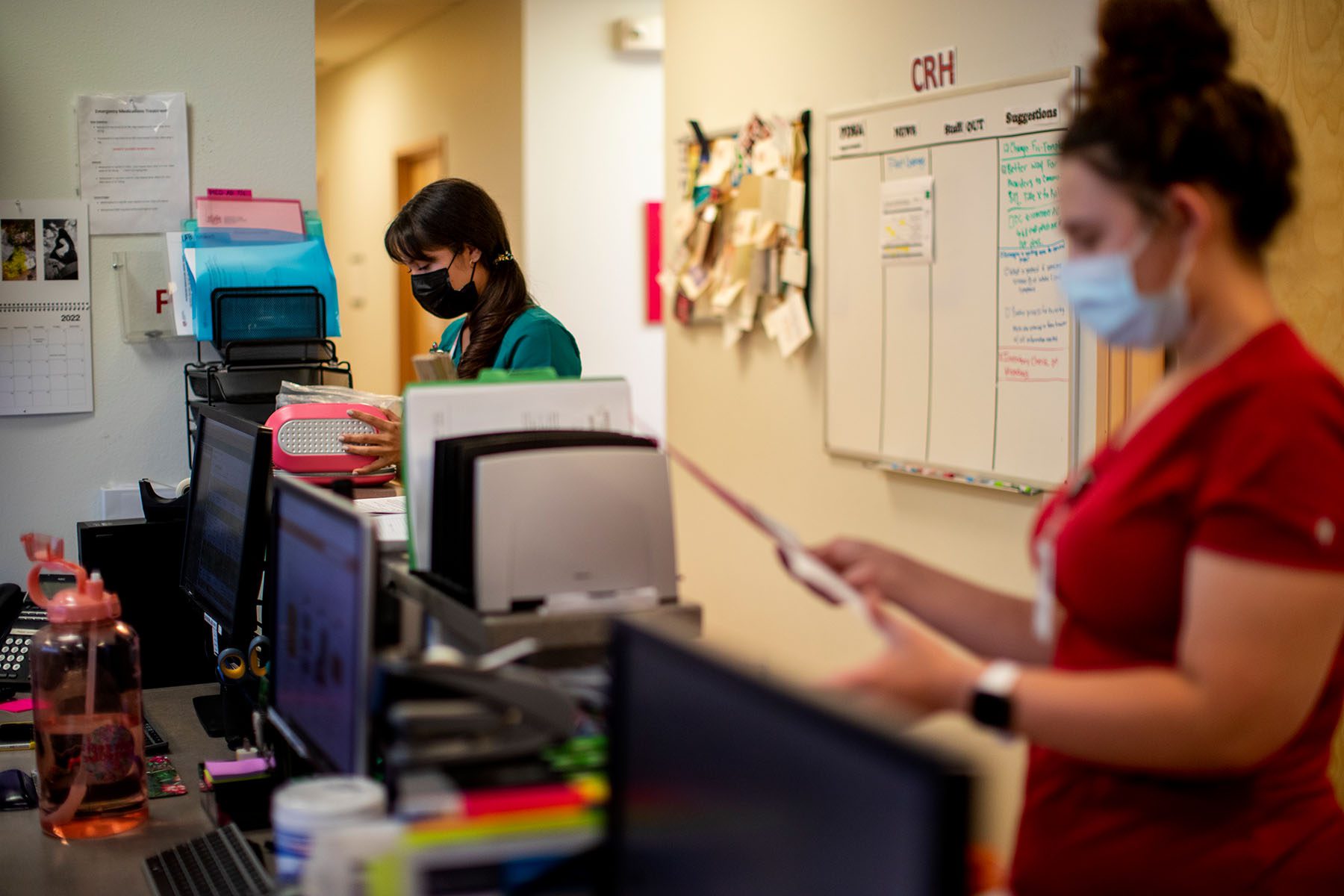

“We are now realizing if we are not at the table then we are going to get written out of the story, and we are not going to be able to control the narrative,” said Gustin, who is the medical director at one of Nebraska’s two fertility clinics, the Heartland Center for Reproductive Medicine in Omaha.

But as those conversations evolve, a difficult question is surfacing: Will fertility doctors be willing to work with anti-abortion legislators to protect in vitro fertilization (IVF), even if it means helping them craft bills that would restrict abortion? Or are they willing to risk the future of fertility care to take a stand on abortion rights?

Thirteen states have “trigger” bans on the books that have gone into effect or will soon, a result of Roe being overturned by the Supreme Court. Many of them include language that defines life as beginning at fertilization. Right now, it’s unclear whether those laws will directly affect IVF. Legislation in Utah may have the most direct impact, the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) has warned. Other states have tried to pass separate “personhood” bills that give embryos constitutional rights. None of those bills have passed, but the end of Roe could open the door to more legislation of that nature.

-

More from The 19th

- ‘We feel kind of powerless’: The end of Roe is overwhelming clinics in states that protect abortion

- IVF patients started moving their embryos out of states with abortion bans when Roe fell

- Many low-income people are already shut out of IVF. Could abortion bans make it even more expensive?

In Nebraska, Gustin has been a vocal figure criticizing a proposed bill that would eliminate abortion access. The bill, which would ban abortions before 20 weeks — the current limit — narrowly failed earlier this year, and the governor is considering calling a special session specifically to reintroduce a version of that law. The original legislation defined life as beginning at fertilization and made it illegal to prescribe medication or perform a procedure to end that “life” — something fertility doctors often do when treating miscarriages or nonviable pregnancies that could result from IVF and other fertility care.

Since it became clear that the state would move to pass new legislation the minute Roe fell, Gustin has worked to set up “Save IVF Nebraska,” a Facebook group that now has more than 1,500 members, to collect stories from patients about their fertility journeys and to organize people to lobby legislators about how abortion restrictions could have a trickle-down effect on fertility care.

Legislators have asked Gustin to tell patients to stop calling them, she said, after being inundated with concerns. At least several legislators have said they will not support an abortion ban that could impact IVF and other fertility care, Gustin said.

Scout Richters, the senior legal and policy council for the American Civil Liberties Union of Nebraska, said she credits the work Gustin and several other IVF doctors, as well as their patients, have done with slowing the momentum of the original abortion ban. It’s now an open question whether a special session will be called.

“IVF doctors and patients have really gotten organized, they’ve been able to really flood senators with their very valid concerns about this,” Richters said. “Because it’s a moment to breathe [outside of a] legislative session, the anti-abortion politicians have no choice but to listen and hear the stories and they can’t bury their heads in the sand.”

Gustin said she is not willing to consider negotiating any exceptions for IVF; in her opinion, “there is no such thing as a good ban.” But nothing is final.

“We are going to hold the line as long as we can,” Gustin said.

ASRM, the national organization of reproductive endocrinologists, is pressing doctors to not help with any anti-abortion legislation. At an ASRM town hall meeting at the end of June, doctors were encouraged to stay united in protesting abortion bans.

“We won’t want to say, ‘OK, if you carve out IVF, I will support your bill,’” said Marcelle Cedars, the organization’s president. “I think it’s really important for all of us to keep the bigger picture [in mind] and to keep our voices loud and together. We are much more powerful together than we are apart.”

But Gustin is not a politician. The no-compromise strategy might work politically, “but as a health care provider, that’s a little bit harder to swallow because if the ban passes, then we’ve done nothing to make it safer,” she said.

Dr. Serena Chen, a reproductive endocrinologist in New Jersey, said she got chills when Gustin told her she and her colleagues may be facing that question soon. The two are part of a group of fertility doctors across the country forming a coalition to fight abortion restrictions and ensure IVF is also protected. Currently that means ensuring specific language is included in bills states are passing to protect abortion, but it could also mean crafting language in anti-abortion bills.

Chen, the director at the Institute for Reproductive Medicine and Science at Saint Barnabas in Livingston, New Jersey, practices in a state where abortion access is being shored up, not cut back. But she said she understands the moral question before her colleagues in other states.

“The Titanic is sinking and you don’t have enough lifeboats. Are we just gonna say let the whole thing sink and let everybody drown? Or are we going to take out some of these lifeboats and try to put as many people in as we can?” Chen asked. “We would love to save all of women’s health today, but if we can only save IVF today, that’s what we would like to do.”

Entering the movement for abortion access is unlike anything Chen has done in her entire career. She said she’s a first-generation daughter of two Chinese physicians, who came to the U.S. to “send me to an Ivy League school, play piano, get straight A’s and go to medical school.”

“Little Asian girls — that’s what we do. We don’t do politics,” Chen said. “This is totally not where I thought I would be, but I feel I have to say something.”

In Texas, Dr. Lowell Ku is feeling similarly compelled. Ku, the medical director at Dallas IVF, said he and many fertility doctors feel they’ve been absent from the movement for too long, and now is the time to march and lobby.

“I hope we are not too late,” he told The 19th before Roe was overturned. After the Supreme Court’s decision, Ku wrote in an email that the “news has awoken a sleeping dragon … WE are all fired up.”

“Many of us around the nation are holding meetings to discuss, rally and come up with a plan,” Ku said. “We are 50 years behind schedule, and we need to catch up and catch up quickly.”

This moment has marked a change in the way fertility doctors and abortion providers have approached reproductive care advocacy. In the past, there has been little interest to band together to speak out on abortion, said Kimberly Mutcherson, a co-dean and professor at Rutgers Law School who focuses on reproductive justice and bioethics. She believes that this moment in statehouses will galvanize doctors.

“I do think that some of the more extreme state legislators are going to see this as a moment to finally be able to move forward an agenda, which they have had for a very long time, which is life begins at conception,” Mutcherson said.

Dr. Robert Hunter, the director of the Kentucky Fertility Institute in Louisville, said the day Roe was reversed changed his stance away from being apolitical in his practice.

“We are a reproductive health care clinic and we are pro-reproductive health care — if there was any question about that, there shouldn’t be anymore,” Hunter said. “Part of me feels a little uncomfortable having to be open about that, but I feel like we are being called to duty now.”

That, for him, also means recognizing that IVF is a small part of a greater reproductive care system. “We are first and foremost women’s health care providers. Subset to that, we are reproductive health care, and subset to that, we do IVF,” he said. He would not be willing to discuss carve-outs to any legislation, he said.

Kentucky is one of the states where an abortion ban, which is currently blocked in court, includes the definition of life beginning at fertilization. Hunter doesn’t believe it will impact his work yet, but if that changes, he’s considering a reality where IVF is more expensive and difficult to access, which could lead him to close his practice.

Gustin worries about the day those discussions will come to head, and she will have to choose — she’s already working overtime to prepare for it. Since Roe was overturned, she has barely made it home in time to kiss her kids goodnight, between working to set up the national coalition of fertility doctors against abortion bans and managing a barrage of questions from patients about the future of their care and their embryos in Nebraska.

“I think not until we are in that situation could I tell you fully what we are going to do,” Gustin said. “At the end of the day, we’ve got to keep going. If we are able to block a ban, then another one will come, another one will come, another one will come.”