Editor’s note: In the months since her death in October 2022, interviews with Sacheen Littlefeather’s sisters have called into question aspects of her story, including her Native American heritage.

Sacheen Littlefeather was 26 years old when she put on a buckskin dress and moccasins, took the stage at the 45th Academy Awards and declined an award on behalf of Marlon Brando. It was 1973. Brando, who boycotted the ceremony, had just won best actor for his role in “The Godfather,” winning against actors Michael Caine, Peter O’Toole and Paul Winfield. And Littlefeather became the first Native American woman and the first woman of color to make a statement at the Oscars.

“He very regretfully cannot accept this very generous award,” Littlefeather told the audience, who responded with audible grumbling, booing and some scattered applause. “And the reasons for this being are the treatment of American Indians today by the film industry and on television, in movie reruns, and also with recent happenings at Wounded Knee.”

The 60-second speech, which aired during the first international broadcast of the Academy Awards, brought more attention to the situation in Wounded Knee, South Dakota, where Oglala Lakota were protesting — but also changed the trajectory of the young actress’s career and life. John Wayne, an actor best known for his Western films, had to be restrained by six security guards as he attempted to storm the stage, according to Littlefeather, and others made the tomahawk chop motion with their arms, a gesture widely seen as racist, as she walked off the stage. For decades, she was professionally boycotted, personally attacked and harassed. Littlefeather said she once narrowly evaded people shooting at her while she was at Brando’s house.

Nearly five decades after her speech, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences said that it is issuing a formal apology to Littlefeather for the “unwarranted and unjustified” abuse, “emotional burden” and “irreparable” cost to her career. It is also hosting an in-person event at the Academy Museum on Saturday to honor Littlefeather with a “conversation, healing and celebration.” The evening will include a conversation between Littlefeather and Bird Runningwater, an Academy member, and several Native American performances. Tickets are free to the public, but reservations are required.

In a statement to The 19th, a spokesperson with the Academy said that it was committed to becoming a more representative, inclusive and equitable industry.

“We are at a time in Academy history where we are actively reflecting and prompting conversation on both the history of the industry and the Academy,” the spokesperson said. “In doing so, we too are being challenged with how we not only address and contextualize film history, but also take necessary steps to facilitate healing and engagement with communities and individuals who have been harmed or marginalized.”

The apology, though decades late, comes as Indigenous writers, directors and actors are taking more prominent roles in the film and television industry.

Kali Simmons, an assistant professor in Indigenous Nations Studies at Portland State University, said the Academy’s apology is particularly significant given Native women’s general exclusion from the history of cinema.

“Indigenous people, and in particular Indigenous women, have been purposefully and systematically excluded because, in many ways, the stories Indigenous people have to tell are really, really challenging — and really, really challenging to the core narrative that our country is built on,” said Simmons, who is Oglala Lakota on her mother’s side and is writing a book on the representation of Indigenous peoples in media.

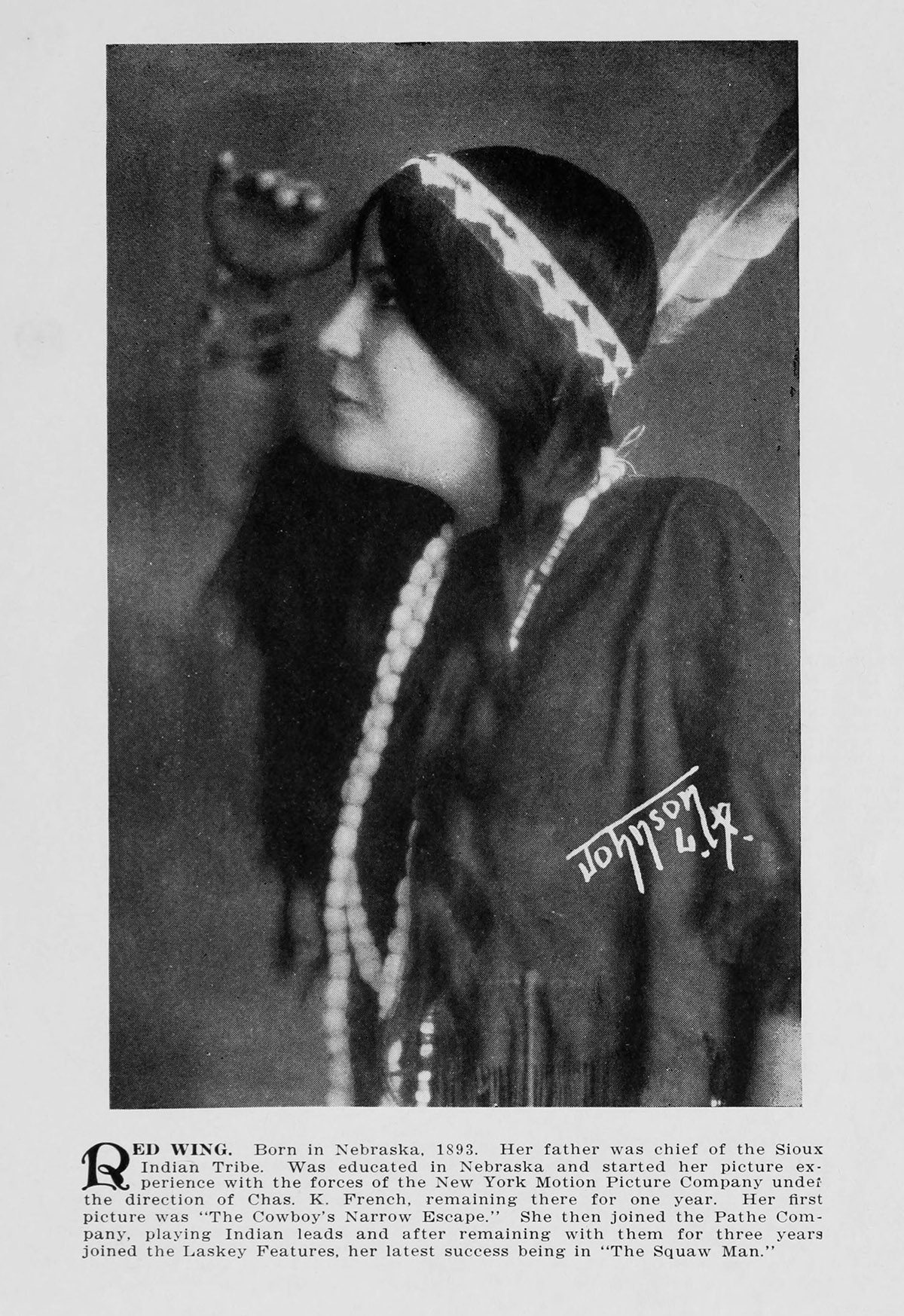

Representation of Native Americans in film dates all the way back to the creation of film itself, Simmons said. In the 1890s, Thomas Edison’s first motion picture studio produced two short films, “Buffalo Dance” and “Sioux Ghost Dance.” A few decades later, Robert Flaherty created the first documentary film, an ethnographic look at the lives of Canadian Inuit Eskimos living in the Arctic. Indigenous people also played an important role in the creation of the Western genre. Lillian St. Cyr, also known as Princess Red Wing, in 1914 became the first Native woman to star in a silent film.

Despite their presence and influence in the early film days, Simmons said, Native Americans were largely constrained to the documentary and Western genres and portrayed as stereotypes. Many times, the Indigenous characters weren’t even played by Indigenous actors, she added.

“A lot of representation fed into this idea that Indigenous people — we’re going to disappear, in part because we’re incompatible with modernity,” Simmons said. “Like there’s just something about us. We can’t figure out how to use a phone; we can’t figure out how to drive a car; we’re just going to disappear.”

-

More from The 19th

- Mary Peltola wins Alaska special election to become first Alaska Native in Congress

- ‘Let’s talk about what truly happened’: Native Americans push for inclusion beyond lessons about Thanksgiving

- Interior Secretary Deb Haaland orders removal of derogatory terms from public land names

This type of representation makes Indigenous genocide a passive process, Simmons said.

“It makes it seem like there’s a problem with us and not a problem with state policies and national policies that targeted us, broke up our families, straight up murdered us sometimes and targeted our cultures in order to disconnect and harm us,” Simmons said.

When Native women were represented, Simmons said, they were typically portrayed as passive and quiet — a stark contrast to Littlefeather on that Oscars stage.

“The fact that there was a Native woman in a very public space speaking and speaking critically about the government and their policies and the treatment of Indigenous peoples was so radical,” Simmons said. “I think a lot of people couldn’t take it. … It was kind of a flashpoint for the representation of Indigenous women. What Sacheen experienced, a lot of other Native women experience.”

The day before the 1973 Oscars ceremony, Littlefeather got a call from Brando, a friend she’d been connected with after the Indians of All Tribes occupation at Alcatraz Island. He wanted her to decline the award for him, he said. Brando, whose involvement in the movement can be traced back to 1964 when he was arrested for taking part in a “fish-in” protest, wanted more attention to be drawn to what was going on in Wounded Knee. About 200 Oglala Lakota had seized and occupied the city for weeks to protest a corrupt administration on the nearby Pine Ridge Reservation. As the tribe split and tensions rose, tribal police and federal law enforcement became involved.

Brando’s secretary typed up a speech for Littlefeather to read, but when the producer saw the length of the speech, he told her she would be taken to jail if she tried to read it in full. So she took a couple of deep breaths, said a prayer and tried to think about what she would say.

“I focused in on the mouths and the jaws that were dropping in the audience, and there were quite a few,” Littlefeather, now 75, said in a 2022 oral history recalling her speech. “But it was like looking into a sea of Clorox, you know, there were very few people of color in the audience. And I just took a deep breath, put my head down for a second, and then, when they quieted down, I continued.”

Brian Twenter, a visiting assistant professor of Native and Indigenous Studies at Willamette University, said at the time of Littlefeather’s 1973 speech, the government had ordered all of the news media to leave Wounded Knee. The Lakota people knew the importance of television coverage in raising awareness and demanding accountability, and Littlefeather’s speech sparked renewed interest from news outlets and was “hugely important” to the continued occupation at Wounded Knee, Twenter said.

“Through no small part at all, Sacheen Littlefeather’s speech brought international attention to the occupation at Wounded Knee, which, along with other movements and protests and occupations around the country, resulted in the discussion again of Indigenous peoples’ rights on this continent,” Twenter said.

The 10-week occupation at Wounded Knee was carried out with help from the American Indian Movement (AIM), a grassroots effort founded in 1968 to address systemic issues of poverty, discrimination and police brutality against Native Americans. The standoff ended in a negotiated settlement and resulted in the founding of the International Indian Treaty Council, which received United Nations recognition in 1975. Around this time, lawmakers began passing laws to protect Indigenous rights, including the Indian Health Care Improvement Act of 1976 and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978.

The fight for Indigenous rights eventually intersected with the film industry’s portrayal of Native Americans. By the 1970s, Simmons said films, including “Little Big Man” and “Billy Jack,” started to portray more “sympathetic renderings” of Indigenous people. These films depicted Indigenous people as human beings and alluded to expressions of guilt for the way Native peoples have been treated in the past.

“These kinds of portrayals were really helpful in directing attention towards Indigenous political organizing,” Simmons said. “It became really hard to ignore all of the AIM organizing and broader pushes for civil rights amongst various groups, including the Black Panthers.”

There was another wave of Native American films in the 1990s and early 2000s, including “Thunderheart,” “The Last of the Mohicans,” “Windtalkers” and “Dances with Wolves.” Many of the films during this era, Twenter argued, still portrayed Indigenous people as needing a savior, typically a White man.

Though “well-intentioned,” Simmons said these films did not examine the deeper issue of the current and ongoing dispossession of Indigenous people.

But that is changing. Simmons said that in recent years she’s seen a “wonderful explosion” of films and shows by Native women, starring Native women, as part of a larger wave of Native-led projects. Simmons pointed to “Reservation Dogs,” a 2021 television series about four teenagers growing up on a reservation in eastern Oklahoma; “Rutherford Falls,” a 2021 sitcom; and “Prey,” the latest installment to the Predator franchise.

“If you tell the same story long enough, that’s the only way people can imagine a certain event going or a certain people being,” Simmons said. “So if you just tell the story that something is wrong with Indigenous people innately, that they’re never going to make it, they’re just meant to disappear — then that’s all people will encounter and will start to believe.”

When she was standing on that stage, facing jeers and international scrutiny, Littlefeather said in her oral history that she thought of her young niece. The 26-year-old knew she was passing the baton on to the Native women who would follow, and they too would “break through the barriers” they faced. And now, Littlefeather said the Academy’s apology is a “dream come true” and a heartening change to the industry she experienced.

“We Indians are very patient people — it’s only been 50 years,” Littlefeather said in a statement. “We need to keep our sense of humor about this at all times. It’s our method of survival.”

Though an apology is a wonderful first step, Simmons said, the Academy should do more to fund Native-led projects and “allow Native people to tell the stories they’ve deserved to tell” for generations. And not all Indigenous-led projects need to be about the Indigenous experience. Taika Waititi, an indigenous creator from New Zealand, recently directed Marvel’s Thor movies and wrote, directed and acted in “Jojo Rabbit,” a story about Hitler Youth.

Audiences also have a role to play, Simmons added.

“The fact that we have new shows getting recognized is good, and that broad audiences are finding these shows and enjoying them is good,” Simmons said. “But I think when Native people really start to challenge things, a lot of people still tend to get scared. So I think audiences need to prepare themselves to better be challenged because our stories are only going to get more challenging from here.”