We’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

History books rarely reflect the experiences of kids in the American gay rights movement. When they do, stories tend to focus on LGBTQ+ children as they navigate coming out. But 40 years ago, fledgling documentarian Joe Gantz started to wonder about families left out of those conversations. As the anti-gay activist Anita Bryant launched her “Save the Children” campaign, Gantz grew curious about the lives of queer parents and their kids, forced to keep their families secret.

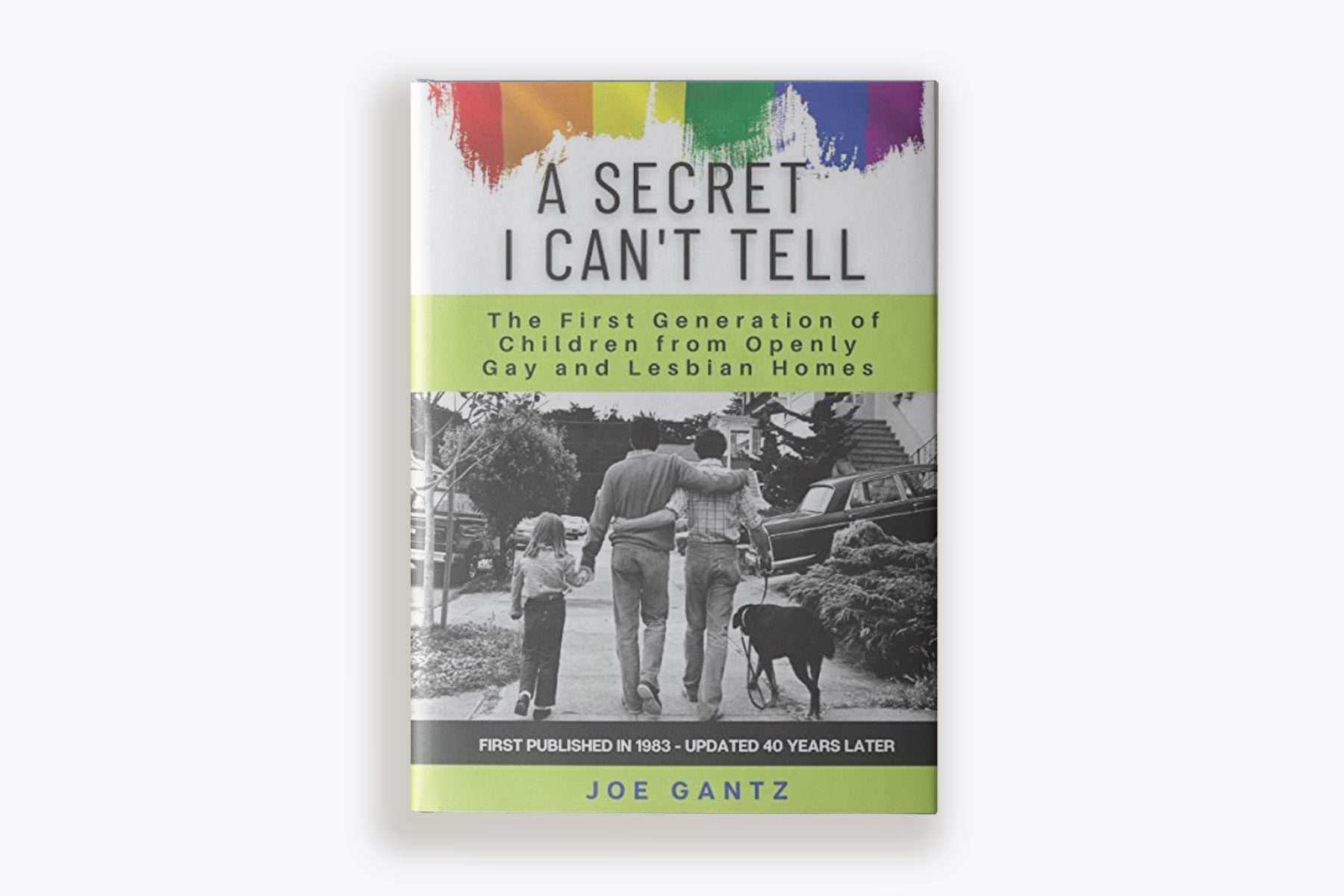

In 1983, he published “Whose Child Cries,” an intimate book that explored the love between queer parents and their kids in a world still largely hostile to them. But as soon as it hit bookshelves, the publisher went bankrupt. Gantz spent four years fighting to get the rights to his book back, by which time its moment had passed.

Now, four decades later, the book is hitting shelves again, this time with fresh interviews with the kids (now middle-aged adults) and a new title. “A Secret I Can’t Tell” is not just a rare history about youth raised by queer parents in the 1980s; it is an eerily timely arrival as anti-LGBTQ+ laws are sending many queer families back into the closet.

In January, the Williams Institute released a study that found that 19 percent of LGBTQ+ parents in Florida had started to hide their sexual orientation or gender identity in response to the state’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill, which took effect in July and bars the discussion of queer issues in elementary school classrooms. While Gantz points out that substantial progress has been made in embracing queer families, his book demonstrates the toll of secrecy on LGBTQ+ families forced to hide who they are.

Gantz said that isolation had profound impacts on the families he interviewed.

-

More LGBTQ+ coverage

- More than half of queer Florida parents have considered fleeing the state in the wake of ‘Don’t Say Gay,’ study finds

- Biden keeps LGBTQ+ remarks brief in State of the Union as queer Americans face hostile legislation

- ‘I’ve been in that room’: How HBO’s ‘The Last of Us’ resonated for a survivor of the AIDS crisis

“I went into it, I think, somewhat naively thinking that I could isolate this issue of what it was like to have a gay or lesbian role model as a parent,” Gantz said. “When I got into it, all these families had been through a [prior] separation. Most had been through a divorce. Many had a stepparent to deal with.”

The book follows the journey of five families in the United States and Canada. Gantz spent a week at a time with each family, returning several times a year for three years, to record and observe. Gantz has changed the names and other identifying information of the families to protect their privacy. At the conclusion of each chapter in the new release, he provides interviews with the now-adult children. Many have kids of their own. In some cases their parents are deceased or separated.

The kids profiled 40 years ago range in age from 7 to 19 and express deep anxiety, fear and isolation as they confront how to talk about their families with friends, teachers, other parents and others outside their homes.

“Usually when someone asks, I just say my mom and Margie are roommates,” says 13-year-old Peter. “I think they don’t want the word scattered around because people would tease us a lot.”

More than bullying, the kids and their parents face the constant threat of separation if the truth about their family structure is revealed to friends, physicians, teachers or in some cases, even other members of their extended family.

“The kids come into the conversation and they say things that are always so interesting,” said Gantz. “They have a way of just being so direct.”

In chapter 1, readers get to know Selena, a precocious 13-year-old living with her father and his partner in Canada. Selena is torn between shielding her gay parents from the judgments of the outside world and wanting to claim pride in her family. Her father, Dan, and his partner, Andrew, carry bags that resemble purses, something that Selena is aware might suggest to people that they are gay. She oscillates between discomfort with living openly and disgust with those who would judge her family.

“When I was younger I invited friends over, and we never thought much of two men sleeping in the same room,” she said. “However, now it’s different. Now, I’m at an age where my friends would know exactly what it means.”

The stressors of navigating a homophobic world take a toll on the whole family. Dan and Andrew openly argue. When Selena reflects on this dynamic as an adult, she attributes much of that tension to the burden of secrecy.

“It was the intensity and the pressure of the secrecy and the potential consequences that was overwhelming,” she said. “And I don’t think I understood how overwhelming it was until I happened to pick up this book again.”

Gantz, who is straight, had hoped to relay portraits of happy kids in the homes of loving gay and lesbian parents. Instead, he found families grappling with the same challenges all blended families face as well as the extra stressors of living in a country hostile to LGBTQ+ people.

“I guess going into it, I wanted to say something very simple like, you know, gay and lesbian parents are great parents, like any other parents, but I think that there is heterosexual privilege,” Gantz said. “I had mixed feelings about the book because it didn’t turn out the way I had anticipated it.”

Today, Gantz hopes readers can embrace LGBTQ+ families that aren’t perfect and perhaps see their own complicated, messy families in them.

“I don’t know if it accomplished what I wanted it to be,” Gantz said. “Certainly not back then it didn’t.”

And that lack of perfection, and forgiveness for it, might be the point after all.