We’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

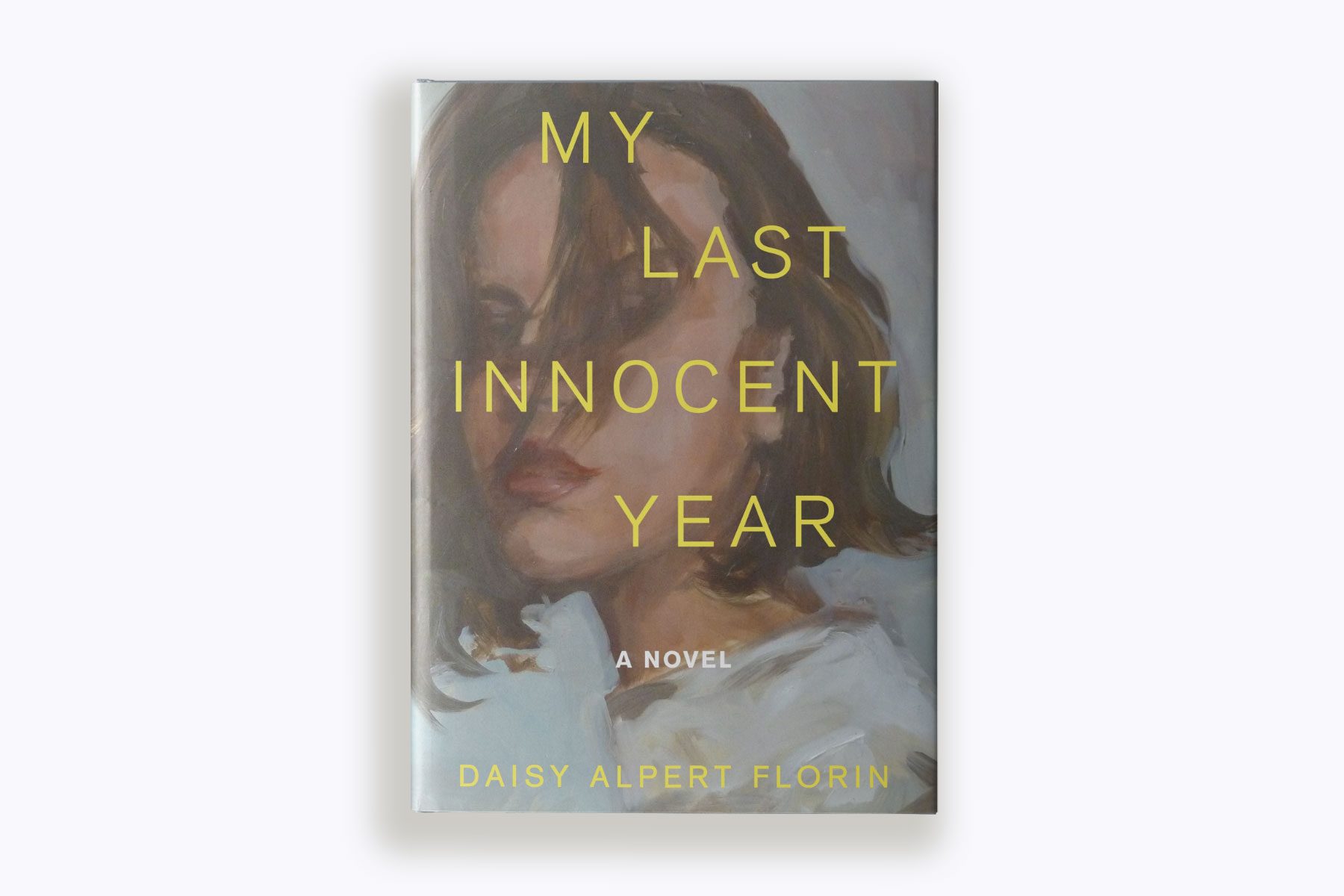

Daisy Alpert Florin’s debut novel, “My Last Innocent Year,” opens with a scene in which Isabel, a college senior majoring in English, has a sexual encounter with Zev, one of the few other Jewish students on campus. She doesn’t want to have sex with him, but feels like she agreed to go up to his room after one of their late-night debates and doesn’t have a right to leave once he begins to have sex with her. She asks him to “slow down” — but never says “no.”

A short while later, Isabel finds herself beginning a relationship with her married creative writing professor, R.H. Connelly — a once famous poet turned small town newspaper reporter. Before Isabel and Connelly have sex for the first time in his department office, he tells her she must explicitly say exactly what she wants him to do, so that there is no question of whether or not she consented to the relationship down the line.

Connelly entered Isabel’s life as a professor as a surprise last-minute fill-in for the English department chair and famous novelist, Joanna, who has taken a leave of absence to deal with her divorce from her husband and fellow English professor, Tom. Tom happens to be Connelly’s best friend and Isabel’s thesis adviser, and at its outset, Isabel perceives the affair with Connelly as an access point into the world of adult relationships before her, and another data point for her continued investigation into what she thinks a successful relationship could and should be.

Isabel continues to find her own voice as a writer of stories about “girls with feelings” while also observing the ways in which neither Connelly’s marriage, nor Tom and Joanna’s now-unraveling marriage, is anything like what she imagined adult relationships could or should be. Oh, and also it’s 1998 and the whole world is watching the Bill Clinton-Monica Lewinsky situation unfold in the national media in the background.

Through intimate, lush prose centered in a specific moment in American culture, Alpert Florin has constructed a novel framed on all sides by questions about what consent means and the way power and gender forever intersect with it, especially as individuals seek to make sense of their own experiences. Alpert Florin spoke with The 19th about what it means to talk about consent and power five years after #MeToo went viral and why she chose to utilize the novel as a way of re-evaluating Monica Lewinsky, 25 years after the former White House intern became a household name.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jennifer Gerson: What made you want to write a novel that is so focused on the themes of consent, power and gender?

Daisy Alpert Florin: I started writing the book in 2015, when I was 42 — before Trump and before the groundswell around #MeToo.

During your college years, everything feels so open and possible — but then decisions end up being made that have tremendous consequences on the rest of your life. Emotionally, that’s what I wanted to go back to: Who was I then and was I still that same person. A lot of what I was dealing with in my early 20s was how I was viewed by men and wanting male approval and validation from external institutions like academia, which tend to be patriarchal.

But then as I was writing, other things started happening — Trump and the 2016 election and #MeToo and [the confirmation of Justice Brett] Kavanaugh. I felt like the world was talking to my book. Every day something else was in the news, and I felt like it was something I had to get into this book.

How did you make the choice to weave the Monica Lewinsky-Bill Clinton situation into the background of your novel and why did you feel compelled to reconsider what that moment meant culturally in this way?

I like books that have a global frame like that, something that gives you a sense of where we are in a book.

I think we’ve been doing a lot of work as a culture looking back at the ’90s and asking how we treated women, like asking, “Wow — how did we treat Britney Spears?” It felt like Monica Lewinsky came out of hiding with her TED Talk in 2015 and seeing that, I really thought to myself, “Damn — what did we do to her? That was crazy.” I realized how much that was the water we were all swimming in for so long and only now does it feel like we’re taking a breath. So I wondered how much did we swallow of that and who decided that this was how we were going to talk about these things: women, consent, power, shame, sex, victimhood.

It turned out to be the perfect frame for my novel: There was this generation one generation older than me who thought she had agency, who were saying, “Well she said the relationship was consensual so why infantilize her and say she didn’t have the ability to decide for herself? Why do we have the ability to say she was in an unequal power relationship?”

In the book, Isabel is very explicitly consenting to a relationship with an older man — it doesn’t have the same power differential because he is her professor and not the president, but I wanted to ask the questions of even though she’s consenting, does she know how to consent and does she know what she is consenting to.

How do you think the conversation has evolved about consent and power from then to today, and where do you see us as being in that conversation right now?

As a parent, I feel like we definitely have these conversations with our kids more than my parents were ever having with me. I don’t think my mother ever talked to me about these things and if she did it was in the sense of, “Oh well, things like this just happen sometime.” I was talking to a friend my age and saying that and she was like, “Oh no, we did! Think — we had Take Back the Night and ‘no means no’ and all that when we were in college!” But it felt like we got to college and had that conversation for the first time then. It’s not like there was any groundwork laid in earlier years.

Now, 25 years later, the next generation is on those campuses right now, and I wonder if we have given them the tools they need to make it an equal place, a place they feel comfortable learning and growing. I don’t have the answer to that.

What do you want people to talk about in reading your novel and revisiting the ’90s and what was happening in regards to gender and power at that time?

I feel like so many people are talking about these ’90s women again and I really want them thinking about the kinds of writing and art they produced then. We had all of these feminist ’zines and women wearing Doc Martens and protesting things on campus in these kinds of vigilante ways, and I really don’t know if that exists in the same way today. I really want people to remember the work that was done then by those women and to see how, no matter the time period, how hard it is for a young woman to come up in the world.

I think we forget sometimes to talk about that there are just things in our world that are harder for women. We as women are very good at sloughing them off, saying, “Oh well, it’s just time to keep going.” I don’t know if there’s always great value in constantly pointing out all of these things all the time — and all the time and all the time — because it really is so constant that sometimes you really do need to just keep on plowing through. But I do want people to realize that sometimes you have to stop and say, “No, look, there are systems here that have been developed and put into place and they really do not work in our favor.” We really need to realize … that there are systems in place that have made things harder for a lot of different groups of people. We need to realize that not everything we see is about personal failings. We need to have more empathy.

-

More from The 19th

- Race, gender, romance — and guns: ‘The Survivalists’ explores creating control in life’s daily chaos

- 40 years ago, an author interviewed the kids of queer parents. His new book explores what they have to say now.

- We asked lovers of Black literature to curate a Black resistance reading list. Here’s what they chose.

Your book is also about domestic violence. Why did you choose to weave a storyline about what domestic violence can look like into a novel about consent and power?

Joanna and Tom were this couple that Isabel admires and thinks of as so romantic because they appear to be this really academically united couple. It makes her think, “Wouldn’t it be great to have a partner like that?” and “Isn’t that what real love looks like?”” — and then I wanted that view to fall apart because this is also a book about that line between childhood and adulthood. I wanted Isabel to see that there is no secret to adulthood, that there’s no set of guidelines that you one day receive and then you have all the answers about how to be an adult. I always knew that relationship had to fall apart in a way that would be really disillusioning to Isabel. She thought they were the model of marriage, but there was actually this intense darkness behind their relationship.

There’s that line in the novel where Connelly says how as you get older, you see that men actually need women more than women need men, and I loved playing with this idea on a college campus. In college, I always perceived that guys could just take women when and how they wanted and women were the ones who wanted “real” relationships and to say, “Please be my boyfriend.” But as you get older, I really do think that men become very dependent on their spouses, and partners and wives. I feel like they are the ones that are so scared of being alone.

What kind of conversations do you think we need to be having today about what consent means and how did you think about peeling back the layers of beginning that conversation?

The one thing I wanted to do in the book the most was ask us all to have empathy for our younger selves. What came through in that practice was tremendous empathy for my younger self — and trying to untangle some of the shame I think we all carry from our youth, the things that happened to us or we made happen to ourselves.

But one of the big questions I ask in the book and continue to sit with is that sometimes people hurt us and they don’t mean to, but harm is still done — so what do you do with that? So what does justice look like in that situation? Do you bring it to the institution to ask for justice? Do you bring it to the criminal justice system? Sometimes these things don’t fit into those kinds of boxes — but you can still be harmed by other people.

I don’t think this is about forgiveness either — I don’t think it’s that you just have forgiveness for other people and then you move on. But I do think it has a lot to do with forgiving yourself. Something else that comes up in the book is choosing to believe things. Maybe you will never have complete clarity so you make a choice for yourself about how you will incorporate certain moments into your life, and then you move on.

There is so much talk about the gray areas that exist around consent in your novel. How do you think consent is defined, given those realities?

I wrote a whole book about consent because I’m not really sure of that answer. What I wanted to do in the novel and what writing the novel helped me acknowledge is that there are these really gray areas and that we can think we want something and then realize that it wasn’t really what we wanted. Desire is messy. We are led by desire sometimes and that can get us behind a closed door we shouldn’t maybe be behind and that maybe we don’t actually want to be behind.

Now there are more systems in place and Title IX coordinators who are more accessible to make sure everyone gets adequate representation, but I don’t know that this is a system that is really helpful to people once you get into the kind of murky encounters that happen when you let a bunch of young people loose on a college campus.

I go back to Monica Lewinsky — I think if that all happened today, there would still be a lot of reporting and headlines around people calling her a slut like we did in the ’90s. But there would be so many other voices arguing the other side, and we didn’t hear those voices in the ’90s. We just had Jay Leno making fun of her every single night on late-night TV and then some older feminists saying, “She can do what she wants! Don’t slut shame her!” But we didn’t have anyone saying in real time, “This is a very young person who has been led astray by a powerful man.” I like to think that today this would be called out as hypocritical and I would hope that our daughters and sons would see that conversation happening and find it helpful.

Florin’s recommended reading

“My Last Innocent Year” is a novel that asks its reader to think about what it means to be a victim and who gets to hold agency when it comes to understanding how power impacts relationships and the very idea of consent.

As the world continues to grapple with these concepts five years after #MeToo went viral, Florin told The 19th, “People need to be able to define their own experiences in a way that works for them. Sometimes, it takes a long time to do that work, and it can take a very long time to process what happened and what it means to you. [My novel] is a book about a woman and a writer finding her voice and speaking out about what is important to her and telling her truth.”

Looking for more novels about the ways women come to understand consent, agency and the power of telling their own stories? Here are three books Florin recommends:

“Vladimir” by Julia May Jonas

This book is just so great, and so smart and also set on a campus. She is writing from the perspective of an older generation — a Baby Boomer — and the setting is in the current day with all of these younger Gen Z activist women on campus. She’s looking around at these younger women and trying to make sense of it all and it is very much about consent and power. I would definitely direct people to read this immediately!

“Asymmetry” by Lisa Halliday

I love this book so much. This is a novel about a much, much older man and a younger woman who is really coming into her own. The entire structure of the novel is a play on how she becomes the writer he never thought she could be. It’s just completely genre-bending. The beginning is this really touching love story — he’s really quite old, so it’s so acute, how that power is shifting between them, because he’s becoming infirm and she’s having to care for him. It’s an absolute must. I want to re-read it now, just talking about it.

“My Dark Vanessa” by Kate Elizabeth Russell

This one is really doing something very different because it’s really the story of the abuse of a child. It’s not even about power and consent, because she’s only 15 years old. It’s really a very difficult read, and I almost couldn’t read it and was physically nauseated while reading it, but I think it’s a really important book. She is an unstable narrator because she’s needing what happened to her to be a love story. You’re watching her try and tell it that way, even though you are seeing the distance between the way she’s trying to present the story to us and the way we’re actually reading it. I think that’s what makes it so difficult to read, but it’s a tremendously powerful book.