We’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

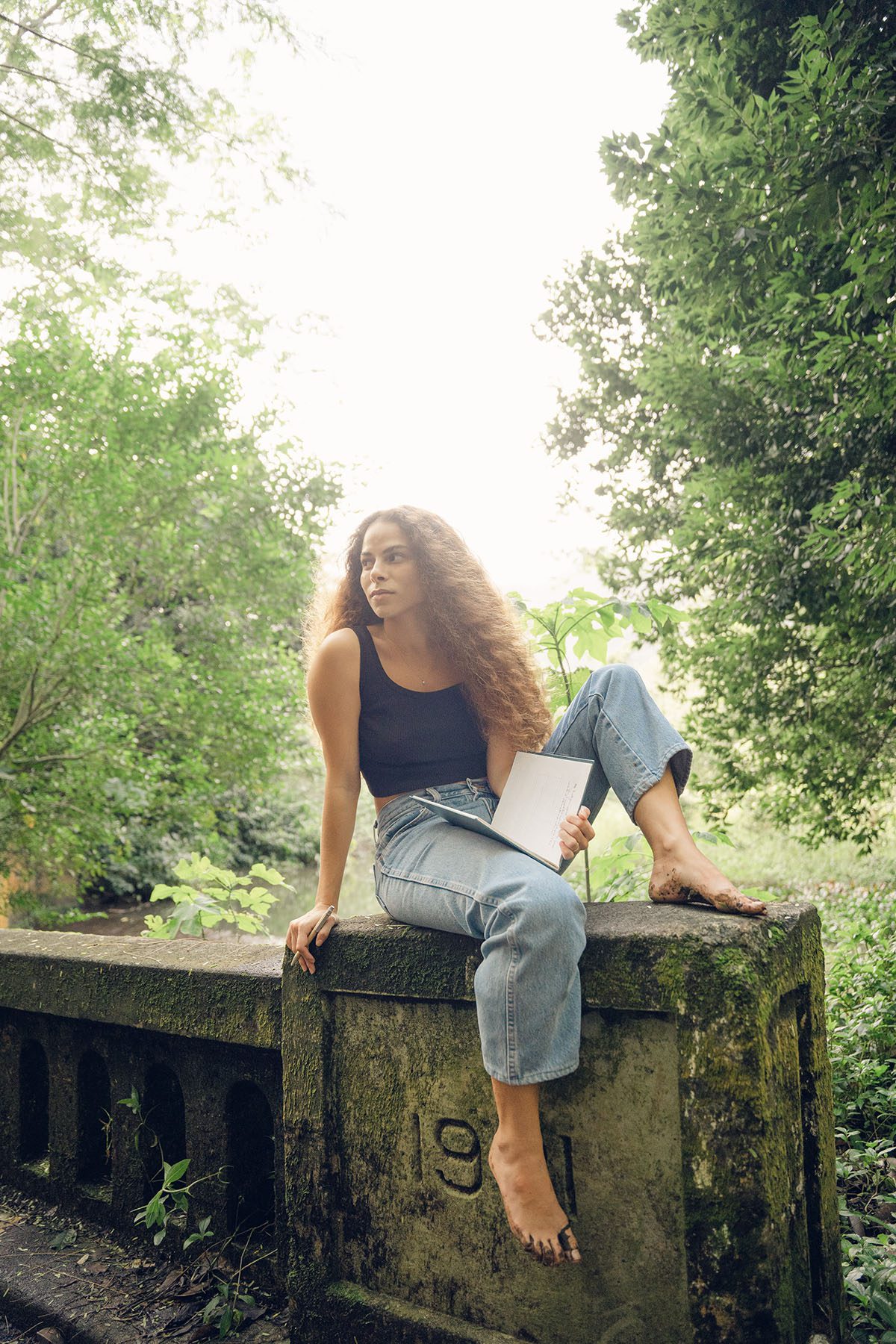

Sage Lenier attended her first environmental class as a high schooler in Corona, California in 2015. It was an AP course that addressed some of the urgent problems facing the natural world, issues like biodiversity loss, climate change and the ravages of industrial scale farming.

One lecture stood out to her in particular: The teacher told the class about the crisis of topsoil loss, or the layer of dirt where most plants — including the crops we eat — grow and flourish. According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, the world is expecting to lose 90 percent of its topsoil by 2050 if countries don’t take action.

She remembers her teacher talking about this fact almost casually, pointing out that once we’ve depleted the topsoil, people will face extreme hunger. Lenier wanted to know what governments were doing about it, but her teacher’s answer was disappointing: World leaders would need to cooperate politically on an international scale that had never before been accomplished. In short, the planet was screwed.

The whole class made her feel helpless.

“I was really, really panicked, obviously,” Lenier said over a Zoom call. “Environmental education as it stands is extremely alarmist, and I was freaking out.”

Her best friend dropped the course because she found it too depressing. Lenier also felt scared by what she was learning about the future of the planet. Instead of ruminating in that fear, Lenier began to wonder what she could do to change things. Her parents and friends weren’t talking about these issues, and this was a few years before the climate youth strikes had raised the profile on the climate crisis.

“I was really confused, really panicked, and wanted to do something,” she said. “What I realized is that maybe our biggest problem is that no one knows any of this stuff.”

After she graduated high school, Lenier began to develop the kind of curriculum she wanted to be taught — one focused on solutions. The University of California, Berkeley, where Lenier attended, offers a unique opportunity for students to teach their own university courses. The classes vary in subject matter from the whimsical — think Harry Potter — to the technical, like computer coding and software engineering, but they all have to meet academic standards to be certified and sponsored by a faculty member.

Lenier’s class, Solutions for a Sustainable and Just Future, was radically different from the environmental education norm, focused on explaining both the most pressing environmental issues of our time, and then offering solutions.

She taught it for the first time in 2018. It broke records for student enrollment, growing from 25 students to over 300 a semester at its peak. So far over 1,800 people have taken the course, including 200 students who took the class virtually during the pandemic through Zero Waste USA. Though Lenier has graduated, it’s now being taught by student teachers she’s helped train. It also won a best practice award from the California Higher Education Sustainability Conference.

According to data that Lenier collected from her students, two-thirds of those who took the class came from non-environmental majors, and more than 70 percent said they had been inspired to, or were becoming involved in environmental work and activism.

Now 24, Lenier is aiming to take her curriculum to universities and high schools across the country. She is at the forefront of a growing movement to integrate environmental curriculum into the education system, equipping students with the knowledge they need to help solve some of the largest environmental issues of our time.

-

More environment & climate coverage

- Mothers of the movement: Black environmental justice activists reflect on the women who have paved the way

- She grew up under water boil advisories in Jackson. Now she’s bringing environmental justice to the EPA.

- Long burdened by environmental racism, activists in Memphis are turning the tide

The state of environmental education in the United States can be described as either nonexistent or woefully inadequate. Radhika Iyengar, director of education for the center of sustainable development at Columbia University, said that most students are having to seek out information on their own through the internet and social media. There is no federal push to teach environmental education, and only a handful of states like New Jersey and Connecticut have made strides in incorporating the curriculum in K-12 schools. When climate change is taught, it is often through a side project or a single lesson.

“This is just the tip of the iceberg that we’re touching,” said Iyengar. “We’re just now trying to integrate climate education when the climate is falling apart, and the earth is falling apart.”

The predominant model of engaging students in environmental work has also overwhelmingly focused on the existential problems at hand. Sarah Jaquette Ray, a professor and chair of environmental studies at Cal Poly Humboldt and author of “A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety,” describes the typical style of teaching about the environment — the kind Lenier encountered in high school — as the “scare to care model.”

“The vast majority of environmental, climate and sustainability educators got Ph.D.s under the assumption that nobody cared or knew enough about the environment and needed to get more educated about it, in order for us to fix this problem,” she said. “Like, if we tell them how horrible it is, if we give them a litany of problems, they will know what to do to go out and fix them.”

But instead it was having the opposite impact, Ray said. “The barrage of problems, the doom and gloom, in general … is having the effect increasingly of leaving people more apathetic, more desiring to numb out [and] more likely to be in denial.”

It is contributing to a growing feeling of despair about the environment among young people. A 2021 survey of 10,000 youth from across the world found that many are suffering from what is known as eco-anxiety, or a sort of existential dread about the state of the planet. Nearly 60 percent of respondents said they were very or extremely worried about climate change.

Students are going to school seeking answers. Lenier’s class provides them.

The course itself not only centers solutions but justice too. What drives Lenier is the people being impacted by climate change and the sometimes faulty response to it. She draws a distinction between capitalism, green capitalism (think Elon Musk and Tesla) and radical environmentalism — the latter being the version she focuses on in class. One that not only upholds care for the planet, but care for the people living on it too. “I care about human rights, first and foremost,” she said.

The course starts with the history of consumption and chronicles the country’s waste streams, pointing out that most of what Americans consume ends up in landfills. This “linear economy” means that resources are extracted, consumed and then disposed of, leading to a rapidly degrading planet and conflict over its finite resources.

But Lenier doesn’t stop there. Her class offers an alternative to the status quo, by explaining the possibilities found within a “circular economy,” one in which things don’t lose their value in a landfill, but instead are recirculated as new items, or are in continuous use, without being viewed as disposable.

Repairing clothing instead of throwing it away, or resoling shoes could be an aspect of the circular economy, versus the fast fashion Americans have become accustomed to replacing at the smallest tear, or hole.

It’s just one example Lenier offers as a window into how an alternative, regenerative future could take shape, one that prioritizes caring for the earth and helps students imagine how they might fit into making it a reality.

“It’s really about getting people excited about what a better world can look like,” Lenier said.

The class offers practical ways that students can take steps in their own lives to limit their consumption, by offering alternatives to daily disposables like paper towels and plastic bags or providing examples of how to engage in the circular economy in small ways, like composting.

This method of focusing on individuals’ actions does face criticism from some environmental activists, who say it detracts from the focus on industry players like oil producers which are responsible for a majority of carbon emissions.

Lenier sees the argument as a cop-out. “Americans, or people of privilege globally, are so willing and able to just absolve themselves of any accountability,” she said. “But if you can see your power as a person in the Global North, it would be transformative.”

Lenier is also advocating for systemic change too. Her class delves into the topics of decarbonization and degrowth — an argument for shrinking the economy — though she thinks individuals, particularly in the U.S., should take responsibility for the harm they are causing to the rest of the world.

Ray said a focus on providing people a blueprint of what they can do in their own lives to limit their impact on the planet has been shown to alter the way they behave.

“It has a psychological effect of making people get more engaged,” she said. “It gives them a model of what they might be able to do in their own community. … So there’s sort of multiple psychological buttons that solutions push when [students are] in classes.”

In some regards, American students are just now catching up to their peers in other countries in simply recognizing that climate change is real. This was something that struck Lovisa Lagercrantz, one of the co-facilitators of the Berkeley class, when she first moved to the states from Sweden when she was 15.

“I felt like my discussions with my peers at school lunches were like, ‘Oh, do you believe in climate change?’ … like it is not something to be believed in,” she said. “The framework in Scandinavia was so far past that. Like it wasn’t a question to be taught, it was a fact. And that was something we were taught in school growing up.”

Ray said there has been an ongoing shift among young people in their awareness of these issues. “Increasingly, the climate is an emotional thing,” she said. “It is intimate, it is a form of trauma, it is a form of fear. It is an emotional topic for many students.”

The climate youth strikes, led by Greta Thunberg in 2018, helped bring the climate crisis to the forefront of students’ minds. But Iyengar also sees this activism as a reflection of societal failure to address the problem to begin with. “We have pushed our students to a last resort,” she said.

Anu Thirunarayanan, another of the current co-facilitators, began teaching the class after they became drained by that kind of activism.

“I think a lot of environmentalists burn out, in a sense, because they see so many of the negative aspects of what climate problems or environmental problems look like. And they are forced to deal with the underbelly,” they said. “And it’s hard to find hope in that.”

They found out about Lenier’s class through a student club, called the Students of Color Environmental Collective, and decided they wanted to shift gears to education and organizing instead of being active in campus rallies.

As a co-facilitator, Thirunarayanan has added to the course curriculum, creating a module focused on environmental justice. This collaboration and student-led approach is what drew them to teaching the class to begin with, and it differed from most faculty-led courses in an important way.

“The identity of our faculty, a large portion of them are White and most of them are men. And I think the fact that this class has been entirely taught by women and nonbinary students, and at least around half of us have been people of color, I think, adds that additional intersectional identity to how the course is taught,” they said.

Now, Thirunarayanan and Lagercrantz are helping Lenier turn the class into an exportable curriculum that could be taught at other universities and high schools through her recently launched nonprofit, Sustainable and Just Future. Her tagline? “Youth-led environmental education for the revolution.”

For Lenier the goal is simple: educate as many millions of people as possible to tackle the problem of climate change.

While still in the early stages of getting funding and figuring out how to run the nonprofit full time, already she is fielding hundreds of inquiries from students at other universities who are seeking to bring the program to their schools. She has plans to develop a digital version of the course offerings, and eventually would like to see the course integrated into K-12 education across the country.

It’s about more than providing solutions, in Lenier’s eyes, it’s about empowering students from across disciplines to “dig into their community” and find the ways in which their skill sets can contribute to solving one of the biggest challenges of our time.

“If we start raising people who have the earth as a priority and also a knowledge of how these systems impact them, and their role in it, and instead of churning out hundreds of thousands more people with business degrees … we churn out people who are empathetic and curious about the world and looking to make it a better place, genuinely,” she said, “I think that is revolutionary.”