We’re answering the “how” and “why” of military news. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

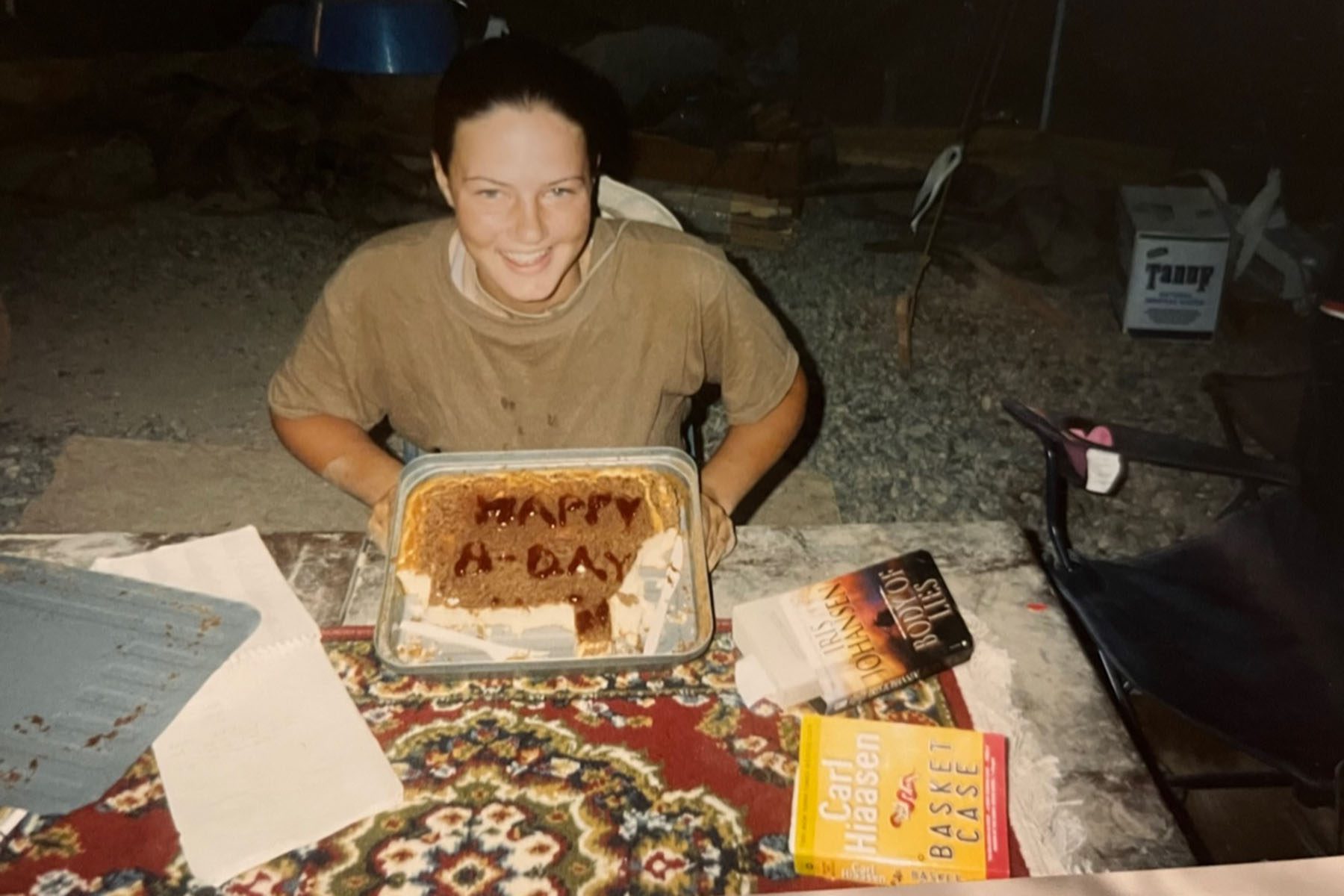

Christina Schauer deployed to Baghdad in March 2003 during her sophomore year in college. At age 20, Schauer was part of an 800-member reserve battalion that consisted mainly of engineers, truck drivers, mechanics and a handful of medics like herself, tasked with building up the military bases that are there now. About 10 percent were women, she said.

“I joined the military knowing that this was a possibility, but it was surreal,” said Schauer, who had enlisted during peacetime in 1999 to help pay for college and nursing school.

For the first couple of weeks, Schauer said, they didn’t have tents. They slept outside their trucks and held up curtains when people needed to shower. It took months to set up tents, flooring, electricity and eventually air-conditioning. During her year in Iraq, Schauer said she faced gunfire, exploding mortars and the constant threat of violence. Whether they were gunners or truck drivers, men and women alike engaged in combat roles — something that became far more commonplace in the conflict.

“I don’t think people think of women serving those types of roles in the military,” said Schauer, who now leads a military and veteran health care program at a community hospital in Dubuque, Iowa.

In the 20 years since the United States invaded Iraq, over a quarter of a million women have served there, the largest-scale and most visible deployment of women in U.S. history. More than 1,000 women had been injured in combat and 166 killed as of 2017, according to the Service Women’s Action Network. The capture and rescue of Pfc. Jessica Lynch made headlines early in the war, and women were among the service members named in the 2004 Abu Ghraib prison abuse scandal. The United States formally withdrew its combat forces in 2011, but maintains a military presence.

The increase in women soldiers, and the visibility of their service, was integral to the military’s mission and ultimately led to major policy changes like the removal of ground combat restrictions for women. Still, according to experts, many women veterans of the Iraq War remain invisible and unrecognized among the larger American public.

Rep. Mikie Sherrill, a New Jersey Democrat, graduated from the Naval Academy in 1994 as part of the first class of women eligible for combat on ships. Congress repealed the law banning women from combat aviation and on ships in 1991 and 1993, respectively. The Navy wouldn’t reverse the policy barring women from submarines until 2010.

Sherrill served for nearly a decade, including a stint in London when she worked for a Navy fleet commander, overseeing the deployment of troops to Iraq and the logistics involved in creating large tent cities.

“The culture for women was not great,” Sherrill said. She said she sensed the difference as early in her career as her time at the U.S. Naval Academy. “I graduated from a large public high school where girls were treated more fairly, but then you’d get to the Academy and slowly there would be an almost inculcation of misogyny. There was this sense that somehow women were lowering standards and that it wasn’t fair.”

When she was still a naval cadet, Sherrill said she and other cadets — including several other women — were deployed on a ship that only had enlisted men on it. After some “weird interactions,” Sherrill learned that the enlisted men had been told not to talk to the women because it would be “nothing but trouble.”

In Iraq, however, Sherrill said that women service members took on some of the more dangerous roles, gathering intelligence and clearing homes of suspected militants. It became clear as the conflict dragged on that the U.S. military needed to engage with Iraqi women, a job only possible with women specialty combat squads — called Lioness Teams. These women Marines and soldiers were encouraged to emphasize their femininity, instructed to take off their helmets, let their hair down and talk about their families or relate to Iraqi women on a more personal level in a way that would have been culturally objectionable if a man had been sent to interview them.

“The front lines are no longer as cleanly delineated in war as they had been in the past,” Sherrill said. The changes put women in places with more responsibility and risk, but often in a way that wasn’t reflected in record-keeping, housing and careers. “So you often had women being deployed to places that technically were combat positions or were deployed on submarines where they weren’t included in the official ship’s company of submarines. Women were serving in all kinds of combat roles; however, they weren’t given the billets, the credit or the promotions that often came with those roles. It was always done in this sort of jerry-rigged way.”

In 2013, Congress announced the repeal of the combat exclusion policy, though it wasn’t implemented until 2015.

“After years of fighting in Iraq, you finally saw an acknowledgment that these restrictions were sort of in name only and really punitive to women service members,” Sherrill said.

In addition to the repeal of the women in combat exclusion, several other major policy changes have been enacted in recent years, influenced in part by the growing visibility of women in the military — and by women veterans who pursued government service in the civilian world. Congress mandated in 2020 that the Marine Corps Recruit Training be gender integrated; the pink tax on military uniforms was eliminated in 2021; and women’s military uniforms continue to evolve. And as part of the latest National Defense Authorization Act, or NDAA, the military authorized increased funding to support military families and reformed how sexual assault and harassment cases were handled in the military justice system.

“As a Navy veteran, I love our military and our service members and our veterans, but sometimes it is difficult to make changes,” Sherrill said, noting that it took years to get military sexual assault and harassment cases prosecuted outside of the chain of command. “I think having women veterans in Congress is a part of that solution. . . . [Former Rep.] Elaine Luria and I had both gone to the Naval Academy, served in the House Armed Services Committee and are in group texts with people who’ve been assaulted in the military — so we understand the issues.”

Theresa Schroeder Hageman, a political science instructor at Ohio Northern University who served as a nurse in the Air Force from 2005 to 2010, said that she’s noticed that veterans like herself who served during the post-9/11 conflict years don’t always claim the veteran status. Schroeder Hageman said she cared for active-duty and veteran patients at one of the country’s largest Air Force hospitals, but she was never deployed overseas.

“Sometimes I don’t claim the status because I didn’t deploy, so I feel less than, which is silly,” Schroeder Hageman said. “You think, ‘I’m not a real vet.’ Some women who were deployed but didn’t serve outside the wire will say they’re not a real vet.”

The 19th reached out to more than a dozen women veterans who served in the Iraq War, but the vast majority declined an interview, saying they did not feel comfortable or qualified enough to speak about the veteran experience.

It’s this kind of mentality, Schroeder Hageman said, that is fed by and perpetuates broader stereotypes about who a veteran is and what one looks like. Schroeder Hageman described women having to work hard to prove they deserve veterans discounts and services. Some opt to “forget about it” and blend back into civilian life.

“Women are the most visible service members — we stick out, everyone talks about us,” she said. “But we are also the invisible veterans because no one sees you as a veteran or they don’t assume you’re a veteran.”

Lisa Leitz, an associate professor of peace studies at Chapman University, said that although “the cultural connection between violence and masculinity is still so strong,” there’s also a growing awareness that combat in modern warfare is more nuanced. Part of that, she said, means mechanics and cooks are often necessary in combat zones, at the mercy of bombings and violence.

Schnauer recalls that feeling of vulnerability. “I remember thinking, ‘Will the other students notice if I don’t come back?’ My first night sleeping outside my truck, I distinctly remember just looking up at the stars and thinking about my family. I thought I was going to die the next day.”

Leitz has noticed that the increased visibility of women soldiers has shifted stereotypes both within and outside the military community.

“Culturally, I do think that the U.S. is becoming more used to seeing women as veterans or as military members,” said Leitz, whose husband served for more than 20 years in the Navy, flying missions over both Iraq and Afghanistan. “It’s still not uncommon, though, to hear from women that they’ve parked in a veteran-designated parking spot and been yelled at.”

Schauer, now 40, said she is intentionally trying to be better about claiming her accomplishments and experiences, and encourages her friends to do the same.

“I feel like when I got out, I didn’t talk about my military service because I felt like I didn’t really do anything,” she said. “I said I just sat around in Iraq for a year and came home, like no big deal. All these other people that did cool things. They deserve recognition, not me.”

It’s not about seeking praise and glory, Schauer said, but about helping other women veterans feel less alone or raising public awareness to get resources to those that are struggling.

“Women veterans in general need to be better about saying, ‘I served too’ and, ‘My experience matters too.’” Schauer said. “And not just downplaying it because we’re women or happy to be wallflowers.”

According to a 2012 report from Yale University, veterans account for more than 20 percent of the overall homeless population. Of the women who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, 77 percent had post-traumatic stress disorder or a mood disorder. The “typical” homeless woman veteran was an unmarried Black woman in her 30s who had never been incarcerated, the study found.

“We have to stand up and talk about our experiences so we can help those other women be seen because as long as people are still picturing a veteran as a man that is in his 60s or 70s, then these women that are struggling with homelessness and brain health issues aren’t going to get the help that they need,” Schauer said.