What do you want to know about LGBTQ+ issues? We want to hear from you, our readers, about what we should be reporting and how we can serve you. Get in touch here.

June is a month of joy, resistance and celebration. In addition to Pride, a celebration of queer identities that stemmed from the Stonewall uprising, June is also Black Music Month.

Black musical traditions, originating in Africa and remixed in the many places Africans were distributed, have left their mark on music worldwide. From gospel to country, from jazz to the blues, from hip-hop to rock and roll, traces of Black entertainers can be found at the roots of many genres. And Black, queer musicians have been there all the way.

When Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton recorded her bluesy hit song “Hound Dog” in 1952, she did it her way. She sang with a throaty growl and howled ad-libs. That was Thornton’s persona: a deliberate refusal to adhere to anyone else’s standards. And it paid off: The song shot up the charts and sold between 500,000 and 750,000 copies.

But a few years later, her rendition would be eclipsed by another version, and the culprit would be dubbed the King of Rock and Roll.

Pride Month: Resistance, resilience, recreation and rest

This story is part of our Pride Month coverage. From lived experiences to in-depth Q&As and survey data, we’re focused on telling stories highlighting themes that reflect the complexity of emotions elicited by this moment in time. Explore our work.

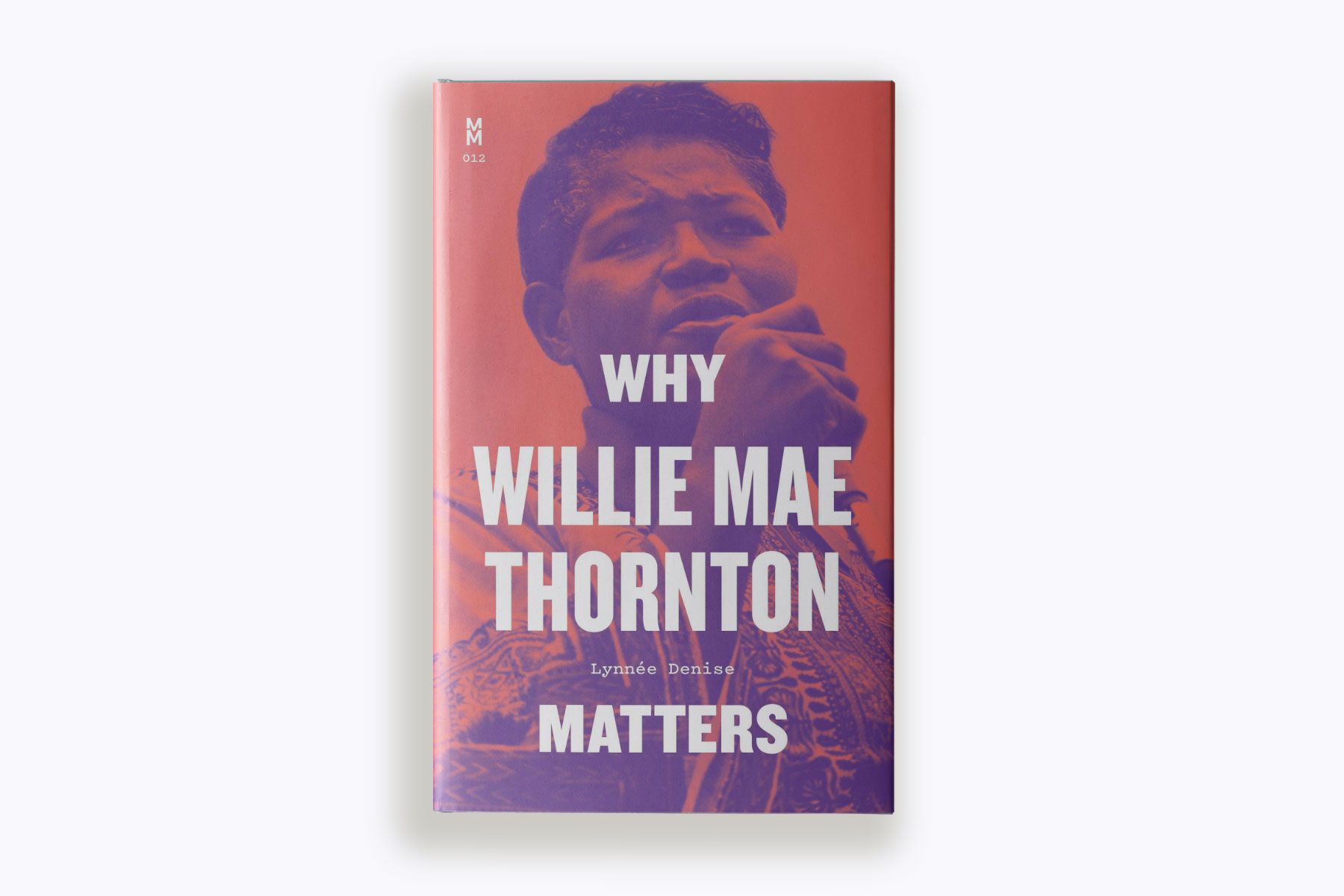

Mentions of Thornton often hinge on that song, but Thornton is so much more than “the Elvis (Presley) moment,” scholar Lynnée Denise said. In her forthcoming biography, “Why Willie Mae Thornton Matters,” Denise reintroduces Thornton as a performer who transcended genres and gender norms.

Thornton died in 1984 at the age of 57.

For Pride and Black Music Month, The 19th spoke with Denise, who dug deeper into Thornton’s story, her identity and her impact.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Daja E. Henry: What sparked your interest in Willie Mae Thornton, and how did you come into this project?

Lynée Denise: I saw this video of one of her performances from 1970 and I was like who the hell is this? Who is this woman commanding the room, commanding the band with all this dignity, all this ruthless inner peace? And her name was Willie Mae Thornton. When I realized that the only story that I really knew about her came from this whole thing with Elvis and “Hound Dog,” in that moment I was like “Oh, we are sadly mistaken.” And we have failed to remember all that she offers beyond her being the first to sing the song and Elvis becoming rich. It was about that 1970 video that just had me stuck.

You mentioned that moment with Elvis and “Hound Dog.” What do you think is the impact of her contributions on music?

That’s also what the video taught me. She performed the song “Ball and Chain.” It’s a song that she wrote in the late 1960s when she was on the West Coast, in the Bay Area, in particular. There was this White woman whose name so many of us know, Janis Joplin. She was a huge fan of Willie Mae and saw Willie Mae perform “Ball and Chain” in some club in San Francisco and came up to her like, “Can we use this song?” Willie Mae scribbles the words to the song on a napkin and was like, “Absolutely.”

What it says to me is that we have the 1950s and her contribution to the early stages of rock and roll, just through her movement through the South and her contribution to something like the Chitlin’ Circuit sound. She made a significant contribution to the vaudeville era, which she grew up in in the 1930s and 1940s. We have the 1960s folk/blues movement that she contributed to and helped shape. We have an interesting 1970s rhythm and blues/blues genre of music that she contributed to, all the way into the 80s.

She comes from a hardcore Christian background, but she has always been clear that as a publicly drinking, cursing, gender-nonconforming, super-tall woman, that she had her own relationship with gospel. She refused to alter for what might be the expectations of the Black church. So you might find Willie Mae singing a gospel song while very, very drunk and not trying to hide it. For her, you weren’t supposed to give up your identity for how other people thought you should understand your own faith. She was like first of all, I’m drunk. I’m fine. I believe in the Lord. And here’s how I want to express this song, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hand.” She does that song on her gospel album that came out in 1971.

She’s contributed to so many forms of Black music directly and indirectly, but then also to American music directly and indirectly.

What do you think is the significance of her showing up in the world the way she did?

She’s just an OG in so many ways. It’s about the architects, thought leaders, innovators, the firsts to introduce something in a context where that thing that you’re introducing isn’t loved or well received. That OG status is also connected to her refusal to care enough to alter who she was. She had a brilliant refusal to care.

I’m also clear that I’m projecting my own language onto her. Willie Mae is not going to be out here talking about “I’m gender-nonconforming,” or “I’m queer” or “I’m lesbian.” Those are not things that she ever said publicly. Those are things that we are projecting onto her because of how she presented physically. And because there are ways that we can expand our understanding of what queerness means. Queerness also is about a level of comfort with the nonnormative. It doesn’t necessarily mean you’re sleeping with the same sex or that you can be simply clocked as lesbian because of how you present. It does mean that she modeled a refusal to adhere to what has been called traditional femininity.

It’s significant because it creates space. It’s significant because it’s part of a long lineage of Black queer folks or Black lesbians who introduced to our community and to the world these different ways of presenting and performing “Black womanhood.” She is part of a genealogy of women who include Gladys Bentley, Rosetta Tharpe, Moms Mabley and maybe later on down the line, someone like Mo’Nique. Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey are on that line too, them both having left behind an archive that lets us know that they, too, are loving and sleeping with women.

Speaking of that genealogy, who are some of her influences?

Little Richard, even though she was older than him.

She’s recalcitrant. She went to the grave being like “Big Mama is influenced by no one.” But at the same time, she’s like let me tell you, every morning I get up and put on Mahalia Jackson. I put on the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi. She was listening to folks like Lucille Bogan, who is a massive Black woman blues figure.

She described her listening practice and she talked about how she would wake up in the morning listening to gospel, listening to, she called them spirituals. That’s interesting, because how do we then sit with all this queerness and then the Black church and what we know about this heavy hand that Black churches tend to rule with around Christian-informed politics of respectability? She’s telling you listen, I’ll wake up, having had a long, long night, might wake up with a hangover listening to the Lord’s word, and then by the end of the night, going back to the club.

The book is titled “Why Willie Mae Thornton Matters.” You use her given name and not the nickname of Big Mama. Was that deliberate?

Yeah. Her name is Minnie Willie Mae Thornton, which is hyper Southern. She’s from Alabama.

These original names say something about place, and about how Black people named themselves when it was legal to be able to name yourself. I wanted to connect her to the South by her name.

But also, in my research, I found that people emphasized her size more than they did her talent. I came across so many music reviews that say things like, she’s a ton of fun on stage and she was 6’5” and 300 pounds of soul and funk. It was just like, you forgot to mention that she was playing the drums. You forgot to mention that she was improvising these lyrics and changing them around on the spot. You forgot to mention that she was playing the harmonica. But you did not fail to mention how big and tall she was, review after review.

She adapted it and adopted it, so I’m not dismissing her stage name. I’m choosing to call her by her name and talk about the context of “Big Mama” throughout the pages. I only allow her to call herself Big Mama. I don’t call her that. She talks about that and she makes something of it that made sense for her and was respectful for her. At the same time, her label, Peacock Records, had songs like “They Call Me Big Mama” and the lyrics start off with, “They call me big mama because I weigh 300 pounds.” It was also a gimmick.

Just thinking about the endless life of Black people on stage and the thin line between Black privacy and the Black public is interesting to me. I feel like calling [her] Willie Mae Thornton is a new entry point for Black folks to reclaim her and learn how Big Mama was used, and then think about how they want to understand her name and her stage name.

Reclaim is a word that comes up a lot. What is it about her legacy that you felt was important to reclaim in writing this book?

There are a million stories about how she was gender-nonconforming. Toward the end of her life, especially, she refused to wear dresses. That’s great context.

I want to reclaim her critical consciousness and her social commentary. In the book, I talk about how she is super critical of [then-President Ronald] Reagan. She stayed calling out Reagan. At live shows, she’d be like, “Y’all know Ronald Reagan just took welfare away, right?” There’s this one skit on the song “Watermelon Man” where she’s trying to negotiate with the watermelon seller, and he’s trying to charge her too much money. She’s like, “I’m going to call Ronald Reagan on you.” She’s using Ronald Reagan as this all-seeing authoritative figure, not necessarily as someone she respects, but as a way to negotiate getting the watermelon for a lesser price.

An extension of that is that she talks about going to jail. She sings from several correctional facilities, which is also very rare because those are positions that are typically held by men. They’re very famous bluesmen like B.B. King and Willie Nelson, White rock men, White folk men. Through the book, I discover that so few Black women [performed] at prisons and correctional facilities. One of my chapters focuses on the three who do. That’s Willie Mae Thornton, that’s Mo’Nique, and that’s Moms Mabley. Three different generations. Those are the only three Black women that I found.

So I’m reclaiming her social commentary, her critical consciousness, and her role in queering the circuit, her role in unlearning the rigid expectations around Black church belief systems and gospel and her refusal to be a victim of the Elvis moment.

For people not familiar with her, what’s the first song you’d recommend as a point of entry?

I would recommend her 1966 album called “In Europe.” She recorded the album in London, which is where I am now and where she was performing for the first time as a part of something called the American Folk Blues Festival. While she was there, she was given the opportunity to use the other musicians who were performing to record a studio album. And the album was important because it was her first solo album outside of her relationship with Peacock, this Black-owned label that exploited the hell out of her and is a part of why the whole Elvis thing happened.

She just had more artistic freedom. So the songs she chose are meaningful because it’s like, ‘Damn, this is the first time I get to do my own studio album.’ She performs on the album as a musician, as a harmonica player, which is something she didn’t do with previous albums when she was signed to previous labels. So it was a big moment in Europe. It’s a beautiful way to enter, and if you’re interested in this early 1950s, early R&B sound, you’ll go back to her Peacock record catalog.

What do you want people to take away from your book?

It’s important for Black people to write Black biographies. It’s important for Black people to write biographies for Black artists, for Black musicians, because there are far too many White people and non-Black people who have written biographies of Black artists. Those stories and the nuances of Black life get lost in translation.