We’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

Amber Bohlman tried almost everything to get pregnant.

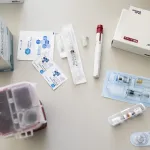

For five years, she took hormones that gave her headaches. Bohlman underwent three rounds of intrauterine insemination (IUI), in which her partner’s sperm was directly implanted into her uterus. Though the procedure was covered by her insurance, which she received through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), she still paid $200 out of pocket each time.

Bohlman, a 36-year-old fish culturist in Fairbanks, Alaska, spent those years hopefully watching her pregnancy tests, only to be disappointed when she saw a negative result each time.

“You get your hopes up every month, and then you have to go through that sadness of it not happening,” she recalled. “You just keep doing that.”

Bohlman, who did two tours in Iraq in her 20s, grew increasingly worried that she would run out of chances to get pregnant. Still, there was one method she still hadn’t tried: in vitro fertilization (IVF), which is generally considered to be the most effective form of assisted reproductive technology. Medical specialists could use her partner’s sperm to fertilize her eggs outside of her body, and then transfer the embryos into her uterus.

But every time she brought it up, she heard the same answer. Unlike her other treatments — the years’ worth of hormone therapy, the repeated IUI treatments, the doctors’ visits and counseling — her health insurance, operated by the federal Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), wouldn’t cover IVF. Beneficiaries can only get covered if their infertility is because of a “service-related condition,” something she had not sustained during her time in the military. And even if she could prove that, there was another barrier: Bohlman and her partner weren’t married, and the IVF benefit only applies to legally married couples.

-

Read Next:

“I was like, ‘Oh my God, how is this a thing?’” she said. “It was like, ‘Why are you forcing me to fit this nuclear family idea of what you want us to look like?’”

Without insurance coverage, the treatment, which would require the couple to fly to Washington State, would cost them at least $20,000, not including travel. It was something they couldn’t afford.

Now, Bohlman and other veterans who cannot access IVF benefits are suing in federal court, arguing that the VA’s policies are “discriminatory and arbitrary.” Some, like Bohlman, aren’t legally married. Some are in LGBTQ+ partnerships and would require a donor to conceive, which renders them ineligible for the VA’s coverage.

The lawsuit, filed earlier this month by the New York City chapter of the National Organization for Women, could have significant implications for the growing cohort of women and LGBTQ+ veterans. Veterans are more likely to benefit from fertility treatment, the lawsuit argues, because they have often delayed pregnancy and parenthood until after they have finished their military service.

The military is still mostly men, but the number of women serving and of women veterans has increased in recent years. In 2021, women made up 17.3 percent of active-duty service members, a 1.1 percent increase since 2017, according to the Department of Defense. Meanwhile, per a report by the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office, women made up 9 percent of people enrolled in the VHA and using its insurance benefits in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available. That marks an increase of 1.5 percentage points since 2015.

There is little recent data about how many VHA-covered veterans are LGBTQ+; an estimate from 2004 suggested that 1 million veterans were gay or lesbian, and 2014 data found that 130,000 veterans were transgender. And the figure of LGBTQ+ veterans has likely grown over the past decade, in part thanks to the repeal of the federal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy that only allowed LGBTQ+ Americans in the military if they did not disclose their identity.

But the organization’s policies haven’t kept up, the lawsuit argues. In filings submitted to a federal court in New York, lawyers for the plaintiffs argued that the administration’s policies violate existing anti-discrimination laws.

“It is one of VA’s top priorities to provide reproductive health care to all Veterans – and we continue to strongly advocate for expanded access to assistive reproductive therapies, including in-vitro fertilization,” Terrence Hayes, a spokesperson for the VA, said in an emailed statement. “We at VA have limited legal authority to provide assisted reproductive technology, including in vitro fertilization, to Veterans.”

Without judicial intervention, the VHA would need an act of Congress to change its policy around IVF. In its contribution to President Joe Biden’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2024, the VA asked Congress to expand its IVF benefit to cover LGBTQ+ members as well as those who are not married. But so far, the idea hasn’t gained traction on Capitol Hill.

This case could force the government’s policy to change, potentially without new laws being written. Still, the process would take months at the very least, and likely longer. The New York case is set to go to a pre-trial conference — in which lawyers for both sides discuss the case before a judge, including whether a settlement is possible — at the end of October. The case wouldn’t be heard in court until after that.

Bohlman had a stroke of luck. She’d received another round of hormones in the mail to start taking, and she’d already begun setting aside money to save up for IVF. But first, she and her partner decided to try getting pregnant one last time without treatment. It worked. She’s now three months along and expecting a son. Finally, she said, she’ll be able to use the baby supplies she has been impulsively buying for years. Her pregnancy is healthy, doctors have told her, but every day, she still can’t quite believe it.

Bohlman has accepted that this might be her only chance at parenthood. Though she and her partner always hoped for two children, it feels like the odds of getting pregnant again are against her.

“We don’t know what the problem was. We don’t know if it fixed itself or if we’d have to redo all those steps again,” she said. “It would be two years [to get pregnant again] if we had to take more pills. And in two years, we’d consider ourselves too old.”

Meanwhile, others worry they may see the prospect of parenthood pass them by, in part because they cannot afford IVF as an option. Another plaintiff, a 30-year-old woman, has all but given up on IVF — she can’t afford it, and because she is married to another woman, she knows that her benefits won’t cover the procedure. She asked The 19th to withhold her name because of privacy concerns.

There is an irony to it, she said. She left the Army a year ago in the hopes of focusing on her family, something that she hopes includes parenthood, ideally within the next five years. But now, as she and her wife study the cost of both IVF and adoption — both in the tens of thousands of dollars — she isn’t sure if she’ll ever be able to have a child. She is currently looking for a new job; if she doesn’t find one that pays enough to make one of those options affordable, parenthood might be off the table for them.

The worst part, she said, is that her insurance treats her marriage as less meaningful or less legitimate.

“This is emotional for me,” she said. “Things that make you feel like your family’s somehow lesser — that’s incredibly disappointing,”

Like Bohlman, she doesn’t expect the lawsuit to affect her ability to access IVF, or to change whether she will be able to become a parent. She realizes, given the timeline, a win in the suit might not impact her personal situation. But she hopes it can benefit other people — and that she can be part of an effort to change other people’s lives, the way previous generations opened doors for her.

“Don’t Ask Don’t Tell was repealed, my wife and I were allowed to get married, even the job I was in in the military was previously barred from women. There were people who fought for that to happen for me,” she said. “When I see this opportunity — I don’t know if it’s going to affect me. But I think it’s my turn. Hopefully I can do that for someone else.”

Recommended for you

Family building has long been a challenge in the military community. Limited IVF access has only made it more difficult.