During my reporting on the Tulsa massacre of 1921, I came across the work of Mary E. Jones Parrish, a journalist and typewriting instructor whose words became a guiding light for me.

Parrish owned a secretarial school in Greenwood, the thriving district of Tulsa known as “Black Wall Street.” The night of the massacre, she and her daughter had just finished a class when the violence began. They fled amidst the flying bullets and blossoming chaos.

Parrish later returned to Greenwood and interviewed scores of survivors, business owners and community members. She went on to write the first-ever book about the massacre, “Events of the Tulsa Disaster,” published in 1923.

The book, which would become foundational to understanding the depths of loss and horror from those days, was just as integral to my reasoning for reporting on the massacre. One particular string of Parrish’s words stuck with me: “Soon we reached the district which was so beautiful and prosperous looking when we left. This we found to be piles of bricks, ashes and twisted iron, representing years of toil and savings. We were horror stricken, but strangely we could not shed a tear. For blocks we bowed our heads in silent grief and tried to blot out the frightful scenes that were ahead of us.”

“Twisted iron.” I thought of not only the strength it takes to unshape iron, but to undo a community, homes and potential. All right down to their foundations.

Surely, today, the iron wasn’t twisted as it was 102 years ago, but I needed to know what shape it had taken.

There are some things that can only be known about the Tulsa massacre and its aftermath by being there. Some truths only emerge while on the ground in Greenwood, which was burned down by a mob of White Tulsans between May 31 and June 1, 1921, after a Black man was falsely accused of assaulting a White woman.

I’ve been transfixed by the story of Greenwood — dubbed “Black Wall Street” by Booker T. Washington — since I first learned about it in school. My teacher then could only tell us so much, and I’ve always wanted to learn more about its past, present and future. My fellowship at The 19th, named for the author, poet, abolitionist and suffragist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, felt like the perfect opportunity to do just that.

What history tells us is that over the course of 18 hours, an estimated 300 of Greenwood’s 10,000 residents were killed, and the equivalent of over $27 million in today’s dollars in damages was done as hundreds of homes, businesses and property were bombed, burned and decimated.

Early on in my reporting I realized there were only so many questions the city once considered the “Black promised land” could answer for me from history books, articles and phone calls — I needed to have my feet in Greenwood. What did the resilience of the community look like after 102 years of rebounding? What was left of the massacre, not just physically, but emotionally, and mentally of the community?

These images from my time there begin to provide the answers to those questions.

I went to Tulsa during the last week of the Legacy Festival, a month of programming that marks the anniversary of the massacre. The events are intended to illuminate the voice and work of Black Tulsans, commemorate the massacre and, as a festival motto says, “Spread truth. Inspire Hope. Extend Tradition.”

“What brings you to Tulsa?” my Uber driver, Vera, asked.

I gave her my elevator pitch, and before the 25-minute ride from the airport was over, she’d called two cousins and an aunt to confirm details as she told me her late grandmother’s massacre survival story that she’d only learned herself five years prior.

Her story wasn’t a unique one. There were so many in Tulsa — sons, daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren — finding out that people they’d known their entire lives had a shared nightmare whose remembrance was never intended to reach the light of day.

But part of the resilience of Greenwood is the persistence of its history, a story that is still being written. What once was a shadow has become a light for Greenwood as residents, survivors and descendants navigate the indiscriminate pain in remembrance and reconciliation.

Even though the massacre happened 102 years ago, its sting and stain are not dampened by time. For the survivors, the memory is as fresh as yesterday. For the generations born of survival, the gravity of the displacement and loss and taking are palpable, as it’s still reaching them today.

The massacre was a defining moment for the place once considered “Dreamland” for the hopes and potential of Black folks, but it’s not the end of Greenwood’s story.

Fulton Street Books & Coffee is a Black-owned shop situated in the middle of a residential neighborhood in Tulsa. The shop’s commitment to bolstering intergenerational literacy and being a safe space for Black and Brown folk was evident from the time I stood in front of it, taking in the flyers offering educational and health resources to the community that mosaic the windows and the intentionality in the author conversations that they host.

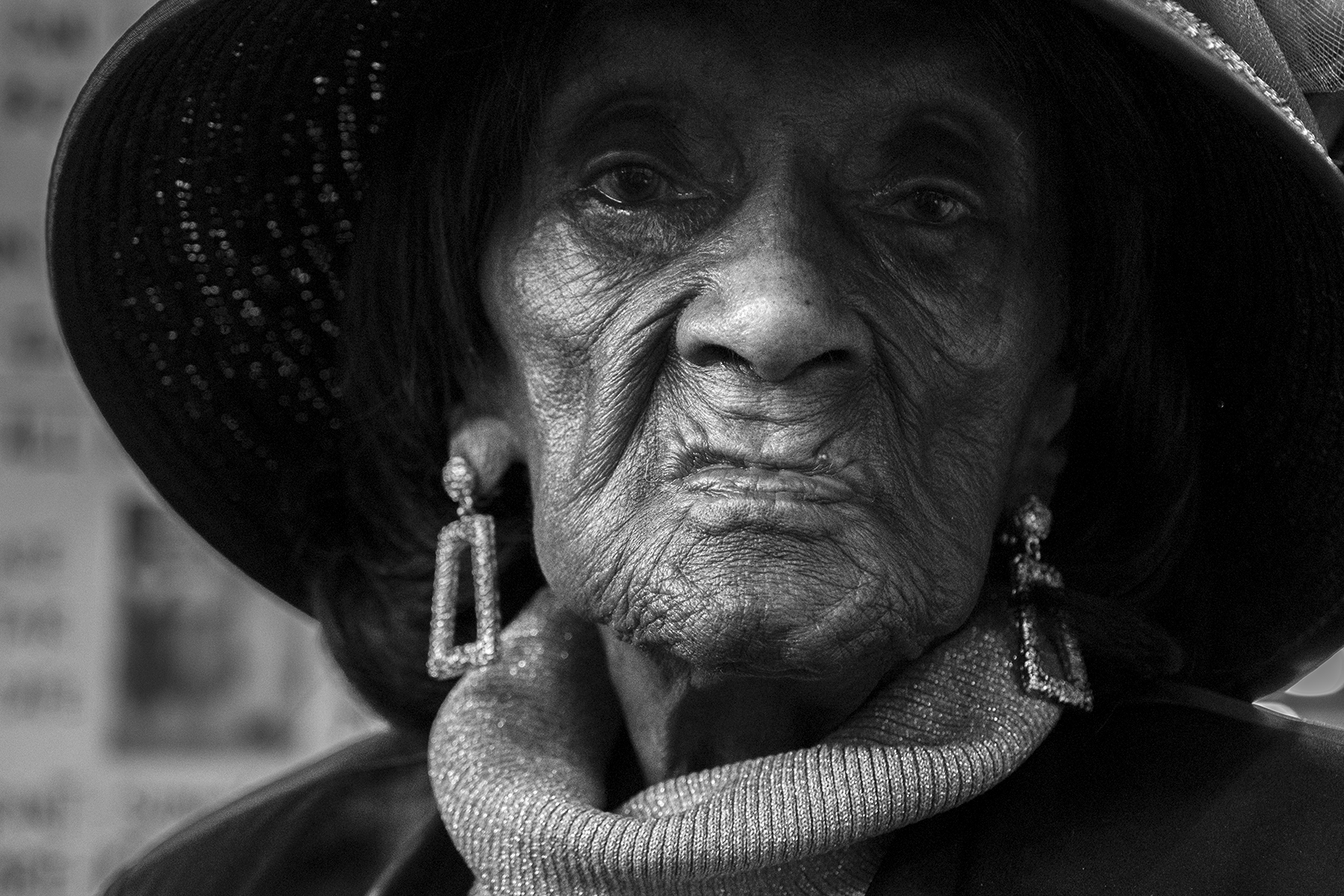

Legacy Week celebrations at Fulton Street saw an increase in kids in attendance this year. KIPP, a charter school in Oklahoma City, brought their honor roll scholars to meet and learn from massacre survivors and their descendants. On May 30, the shop held a press conference and meet-and-greet with Viola Fletcher, the oldest living massacre survivor who just published her memoir, “Don’t Let Them Bury My Story,” at the age of 109.

During the ribbon-cutting ceremony for his Fixins restaurant, former NBA player Kevin Johnson spotlighted Fletcher and the other survivors and thanked them for being in attendance. Although she was only 7 the night the massacre started, Fletcher still remembers the smell of her home burning 102 years later. Since then, Greenwood has faced deep challenges spurred by systemic inequities and oppressive policies like urban renewal and redlining that have stymied rebuilding. Still, Greenwood residents have hope. One source of this hope stems from investors like Johnson pouring into the community’s economy.

Another is the hope, although tempered by dismissals, of a lawsuit against the city of Tulsa for reparations that the survivors and the descendants have been pursuing since 2020. Following a dismissal with prejudice by Judge Caroline Wall on July 7, attorneys for the survivors appealed the decision to the Oklahoma Supreme Court. Last week, the state high court agreed to hear the survivors’ appeal and decide if their case will be sent back to district court and on to trial.

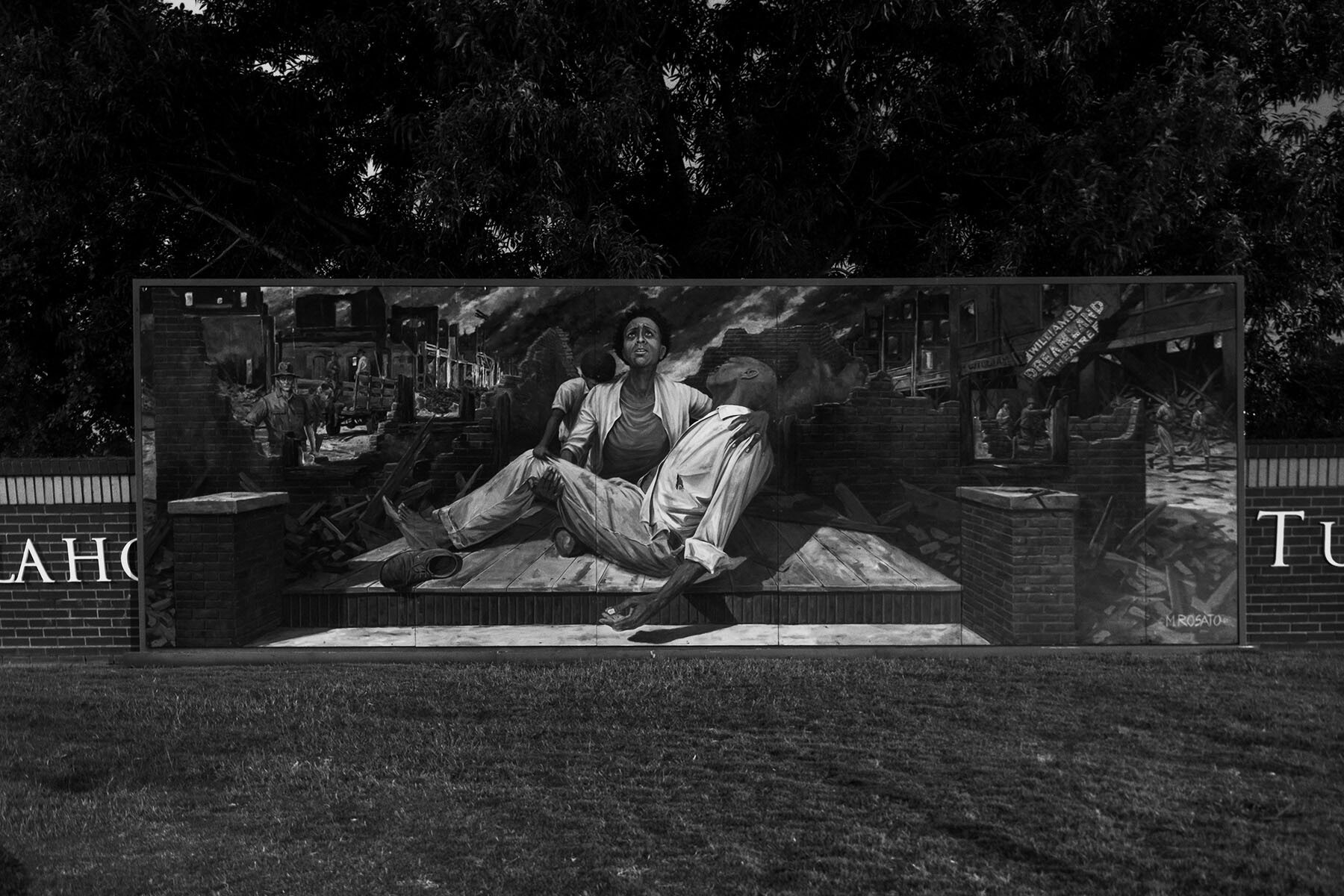

In 2020, Tiffany Crutcher, director of the Terence Crutcher Foundation and descendant of Rebecca Brown Crutcher, a Tulsa massacre survivor, commissioned the artist Michael Rosato to create a mural after seeing one of his pieces depicting Harriet Tubman. Unveiled in 2021, the mural is across the street from the Greenwood community center, directly in front of the Oklahoma State University -Tulsa campus sign and, as Crutcher says, “serves not only as a reminder, but an invitation to remember and be mindful of how we got here and where in too many places, we still are.”

“Both these places are my home. When they’re this connected, you can’t just rep one,” Jesse Tipton said of his tattoo showing love to both Tulsa, where his family was born, and Los Angeles, where he grew up. His grandparents, who were survivors of the massacre, passed on their history, and as his cousin Roberta Clardy (right) said, “made it impossible to forget.” Like hundreds of other descendants, Tipton’s family left town. But he always returns to spend time with relatives and to remember what his folks went through in Tulsa and that they made it to Los Angeles. Clardy was born and raised in Tulsa, and now works as a local historian and tour guide. Although she teasingly calls Tipton one of her “California cousins,” she affirms their family’s deep connection to Tulsa.

The Vernon AME Church is the only Black-owned building to survive the massacre. The church was founded in 1905, and in 1919, construction was completed on the basement of the building. That same basement lent haven to Greenwood residents fleeing the horrors of the massacre on May 31, 1921. As they waited to see if the fire and destruction in the buildings and foundation above would reach them, they huddled together and waited through the night. Although the rubble of their church lay around them, members returned following the massacre to have communion, and give aid and food to those who’d lost their homes and businesses. Today, the basement is the only part of the original building that remains.

Reading about that night was one thing. Standing under the rebuilt and renamed Historic Vernon AME Church, waiting for the neon red cross above the church’s entrance to wake up, was another. The sign is a new addition, part of long-awaited renovations to the building. The church stands as evidence to what community members call Greenwood’s resiliency.

At 108 years old, Lessie Benningfield Randle, affectionately known as Mother Randle by her family and community, is the second eldest of the three remaining massacre survivors. On May 31, she attended the opening of Fixins restaurant in Tulsa along with the other two survivors, siblings Fletcher, 109, and Hughes Van Ellis, 102. Randle, like other Greenwood residents, continues to face deep challenges spurred by systemic inequities and oppressive policies like urban renewal and redlining that have blocked rebuilding efforts. In 1980, Randle lost her home when the city of Tulsa took it as a part of their urban renewal project. Despite these challenges, Greenwood residents continue to have hope.

The Greenwood Rising Black Wall Street History Center, a project of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, opened to the public in 2020. The center is an amalgam of inspiration from places that honor, hold and teach African American history, like the renowned Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

The building bears a quote from James Baldwin that made me feel as if I’d arrived in the right place: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”