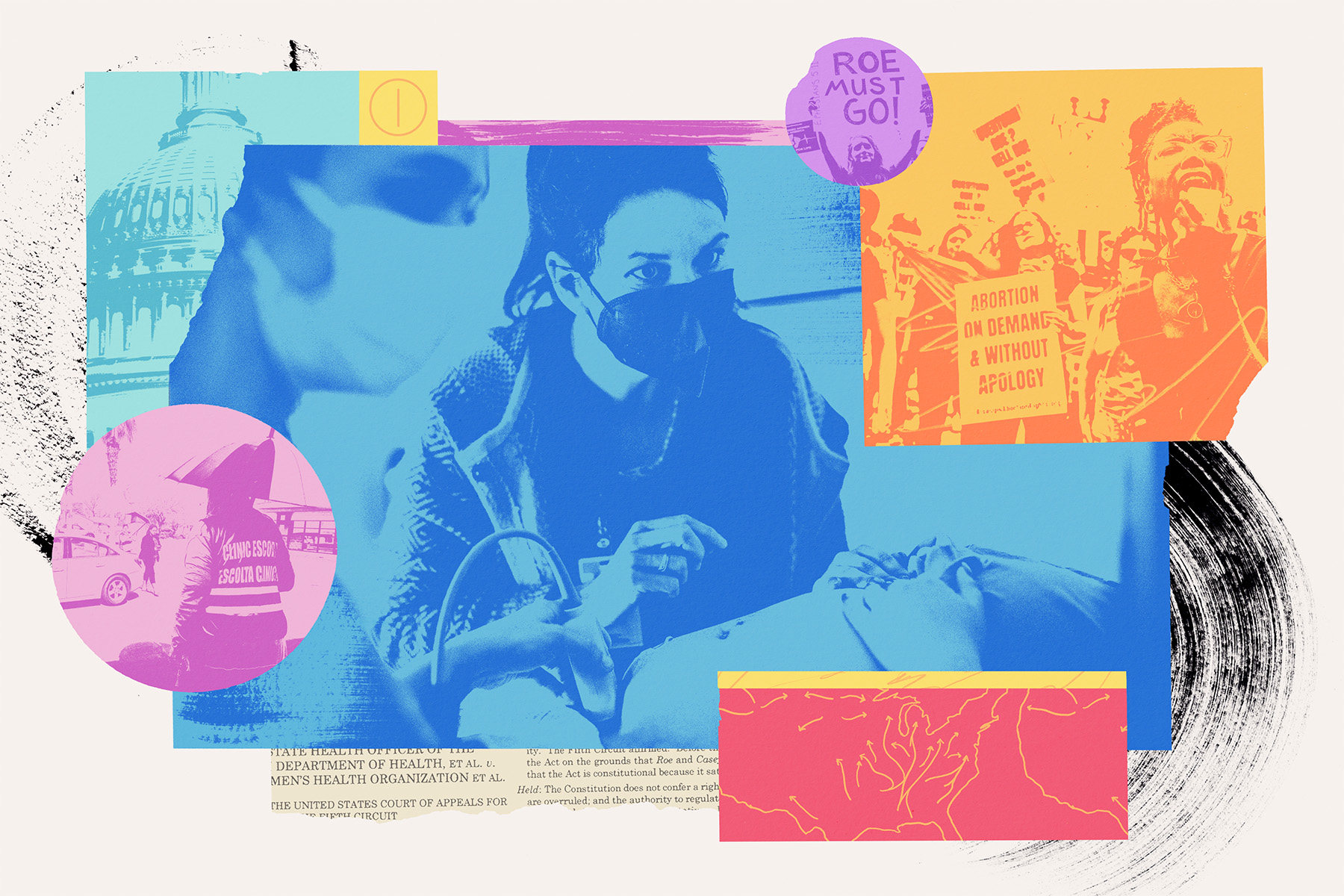

Two years after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the number of abortions performed in the country is up. But that’s only part of the story. In many places, they are also much harder to get or provide.

Clinicians nationwide provided more than a million abortions in 2023 – the highest in the country’s recorded history — in the first full year since Roe’s fall, according to the nonpartisan Guttmacher Institute. That’s the result of a dramatic change in how people get abortions: Rather than receiving clinic-based care in their home states, people are increasingly traveling across state lines, or going online to obtain drug prescriptions. Almost 200,000 people traveled to another state for an abortion. Data from the Society of Family Planning suggests that 1 in 5 are now done through telemedicine, in which a health care professional prescribes and mails abortion pills for a patient to take at home.

Yet those changes have stretched the nation’s abortion network to its limits. Providers in many states report weeks-long wait times. For patients, traveling is more expensive and time-consuming, and nonprofit abortion funds don’t have enough money to support everyone who calls for help. And while telemedicine has expanded access— both in places where abortion remains legal, and in states with bans — abortion opponents, reeling from a recent loss at the Supreme Court, are still looking for new ways to curtail access to the pills involved, mifepristone and misoprostol.

“It’s an inequality story,” said Caitlin Myers, an economist at Middlebury College who studies abortion trends. “The poorest and most vulnerable people get trapped. A lot of people still get out. And then there’s this group of people for whom figuring out how to make a multi-day trip — monetary costs, time off work, child care — all of that is just impossible. And some of them use telehealth successfully, and some of them don’t.”

It’s still too early to understand just how drastically the end of Roe has shaped people’s ability to get an abortion. That’s in part because laws keep changing. Currently, abortion is almost completely illegal in 14 states, and banned after 6 weeks of pregnancy in three more. North Carolina and Nebraska ban abortion after 12 weeks, and a 15-week cutoff is in effect in Arizona.

But research has already shown that people’s lives have fundamentally changed. In a study published last year, Myers’ team found that in the first half of 2023, births in states with abortion bans went up by an average of about 2.3 percent. The effect was greater for Latinas, women in their early 20s, and people in Texas and Mississippi. She estimates that close to 1 in 4 people in states with bans who wanted an abortion did not get one.

“Bans are stopping people who want abortions from obtaining them. Not all of them, by any means, but they are stopping people,” Myers said.

In the subsequent six months of 2023, fewer people seeking an abortion were denied, a change Myers and other researchers attribute to the rise of shield laws, state-based protections for health care professionals who mail abortion pills to people in states with bans. The Society of Family Planning data estimates that, on average, 8,000 people receive pills through shield laws each month — just under half of all telemedicine abortions.

Yet this system has its limits. Shield laws only protect providers in the states where they were enacted: California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Vermont and Washington. Not all patients seeking to overcome their states’ abortion bans can use telehealth, because medication abortion becomes less effective after the first trimester. Not all can connect with the few providers who offer the service.

And though telehealth is medically safe, and abortion bans don’t criminalize pregnant patients, they can still be deterred if they are unaware of the law’s exceptions, or worried they might be prosecuted under other laws, instead. “Not everyone is going to risk the criminalization and the penalties,” said Calla Hales, who runs A Preferred Women’s Health Center, which operates clinics in North Carolina and Georgia.

Such clinics — which are still responsible for the vast majority of abortions in the United States — are becoming stretched to capacity.

“I would be lying to you if I told you anything other than I think about quitting at least once a day every day,” Hales said.

Hales’ Charlotte clinic now mostly sees patients from outside of North Carolina. They’re open six days a week, and perform abortions for about 1,000 patients per month. State law requires patients to make two clinic visits separated by 72 hours — meaning they see each person at least twice.

Often, patients have driven hours each way, bringing their pets or their kids because they don’t have reliable child care at home. Hales has begun keeping coloring books and crayons in her office. “It’s just something I never accounted for,” she said.

Newer bans could stretch the abortion network further, especially a six-week ban that took effect on May 1 in Florida, the third-largest state. Last year, about 80,000 abortions took place in Florida; 11 percent were for people who had traveled there, mostly from other southern states. Already, Myers’ research has shown longer wait times at clinics in North Carolina, Virginia and Washington D.C., the closest places where abortion remains legal after 6 weeks.

And abortion funds, the nonprofits that help people cover the costs of abortion and travel, are receiving fewer donations, even as patients must travel further. A trip can cost thousands of dollars, especially when patients need last-minute plane tickets and hotel nights.

At a Feminist Women’s Health Center, in Atlanta, patients past Georgia’s six-week limit often don’t have the means to travel, said MK Anderson, a clinic spokesperson. Most of their patients don’t have paid sick leave – they’ll have to forgo days’ worth of wages in addition to paying for the journey and procedure.

“It’s a choice that patients have to make,” Anderson said. “And we don’t have a lot of control over how that plays out with them.”

Qudsiyyah Shariyf, deputy director for the Chicago Abortion Fund, said her organization is seeing a steady increase in patients coming to Illinois from Florida and other southern states. The organization will need to spend an extra $100,000 per month to account for the influx.

And there are limits to what it can provide, especially for patients seeking child care or help getting time off work. “We can’t offer child care to everyone across the country,” Shariyf said. “We don’t have that resource.”

Some abortion opponents have tried to deter people from traveling, targeting the funds and pushing for municipalities to create civil liabilities against helping someone travel for an abortion. So far, those efforts have had little impact, and could face heightened constitutional scrutiny.

Instead, anti-abortion groups are prioritizing telehealth restrictions. But there, too, they’re hitting political roadblocks. In some states, lawmakers are concerned about political backlash in an election year, with polls showing that most Americans oppose draconian abortion bans.

“There are still some really hard policy solutions to develop and to pass,” said John Seago, the head of Texas Right to Life, an anti-abortion organization.

His organization has pushed for Texas to enact a policy that would block internet service providers who connect people to telehealth websites. They’ve also suggested legislation that would require credit card companies to flag payments that could be for telehealth abortion, similar to a gun law in California. But Texas legislators, who convene every two years, have passed no new abortion restrictions since Roe’s overturn.

“The message is getting out to break the false narrative that Texas is abortion-free,” Seago said. “However, we still have some major difficulties in getting that message out and in people really feeling urgency.”

Lawmakers in other states have also sought to deter telehealth organizations: Last month, Arkansas’ attorney general sent a cease and desist letter to Aid Access, a major provider, and soon after, Louisiana lawmakers passed a law that would treat abortion pills as “controlled dangerous substances,” though it explicitly exempts pregnant patients from penalties. Those efforts could have chilling effects, deterring people from using telemedicine, though it’s not clear how they could actually be enforced.

National abortion opponents are looking for new strategies. Earlier this month, the Supreme Court dismissed a case originally from Texas that could have undercut access to mifepristone by reversing the Food and Drug Administration’s decision to approve it for use in telemedicine. The court found that the doctors who filed suit had not proven they experienced harm from the pills’ availability, and didn’t have standing to sue. But the court didn’t weigh in on the merits of the case. That leaves an opening for other plaintiffs to challenge mifepristone’s availability. Already, attorneys general in Idaho, Kansas and Missouri have taken steps to do so.

“You have three states standing in the wings,” said Kristi Hamrick, a spokesperson for Students for Life Action, the political arm of the anti-abortion group Students for Life. “I’m sure other states will join.”

Former advisers to Donald Trump, the GOP nominee for president, have suggested that a Republican administration could leverage 1873’s Comstock Act, which forbids the mailing of “obscene” materials, including abortion-related materials, and push the FDA and Department of Justice to reverse approval of mifepristone and to prosecute organizations that mail pills.

Trump himself hasn’t said how he would handle the issue. While the Supreme Court did not comment on Comstock in June’s mifepristone ruling, two conservative justices mentioned it in oral arguments earlier this year. Meanwhile, worried Democrats are pushing to repeal it.

Should future challenges to the FDA’s mifepristone approval succeed, it could imperil other drugs including emergency contraception, which some anti-abortion activists argue is an abortifacient, a characterization in defiance of medical consensus. In Congress and state houses, legislators are already battling over access to contraception.

“It feels fragile,” Myers said. “The Supreme Court could have rolled back telehealth access, but instead they said the plaintiffs didn’t have standing. It feels a bit like kicking the can down the road, and I would be shocked if this is over. If mifepristone access were curtailed, if telehealth abortion were reduced in some ways, those could be major chunks to this fragile equilibrium.”