Your trusted source for contextualizing Election 2024 news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

About a month before Arizona’s July primary, Pima County Recorder Gabriella Cázares-Kelly and her older sister Elisa Cázares were driving around Three Points, a rural community between Tucson and where they grew up on the Tohono O’odham Nation, dropping off flyers for the recorder’s reelection campaign. Some 5,000 people live in Three Points, which leans conservative. The properties, an assortment of mobile homes and ranch-style houses, are separated by chain link fences, but their yards blend into the Sonoran desert landscape of mesquite trees, saguaros and chollas.

They stopped at a trailer whose address popped up on a canvassing app on Cázares-Kelly’s phone, programmed to scan voter rolls and identify homes of registered Democrats who voted in the last election. Old Volkswagens were rusting in the yard. There was a “beware dog” sign attached to the fence. No one came out to greet them, so Cázares-Kelly left her campaign materials wedged outside. Her sister made a note of it on the phone as a “lit drop.”

At the second stop, Cázares-Kelly — dressed in tennis shoes, distressed jeans and a black shirt that says “Elect Indigenous Women” in big white letters — had just tucked fliers under a car’s windshield wiper when a little girl opened the door of the house, followed by a woman sporting a slightly wary expression.

“Hi. My name is Gabriella. I’m actually the county recorder. I’m running for reelection and just sharing some information about my campaign,” Cázares-Kelly said warmly through the fence, the sun beating down on her long black hair.

Cázares-Kelly, who is Pima’s first Indigenous person to hold a countywide seat, quickly explained that part of her job is to be responsible for early voting, mail-in voting and voter registration. She was there soliciting voters for herself and also canvassing for her best friend April Ignacio, who was running for a Pima County Board of Supervisors seat. They grew up together on the Tohono O’odham Nation and got into politics to bring more rural and Indigenous representation to a county where about 4 percent of the residents identify as Indigenous and whose votes could help decide a closely-contested November election in a battleground state.

Over the loud barks of two dogs, the woman explained that she can’t vote because she has felonies on her record. Cázares-Kelly’s demeanor shifted as she began talking about her favorite subject: voting rights. She told the woman about a free legal clinic provided by the county’s public defenders where she might be able to restore her voting rights and that all the information is on the recorder’s website.

“Oh really?” the woman responded, her eyes lighting up. “That’s the only reason I haven’t is because it costs so much money.”

“They’ll help you fill out the paperwork,” Cázares-Kelly said reassuringly.

Cázares-Kelly headed back to the car and reported to her sister about the possible voter education win. “That was cool,” she said.

Her sister noted the interaction in the app and looked for the next address.

Most stops resulted in lit drops at homes whose residents don’t seem to trust strangers walking up to their doors. At one, Cázares-Kelly was already on the front steps when the word “shotgun” on a sign caught her eye. She turned to the Ring camera and explained why she was there before briskly getting off the porch, entering the car and telling her sister to book it.

To Cázares-Kelly, each conversation feels like a small victory. It’s rare to have politicians canvas in these harder-to-reach communities, including those on Indigenous lands; almost everyone perks up once she explains who she is and what she’s doing.

She doesn’t really need to get the vote out to be reelected; in solidly Democratic Pima County, it’s extremely unlikely that a Republican would flip her seat. But as a member of the Tohono O’odham Nation, whose broad territory extends along 62 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border, she knows the obstacles to participating in elections. It’s the whole reason she ran in 2020: to represent people who were being ignored by the democratic system and denied the right to vote.

But Indigenous voters can swing election results in this battleground state, home to 22 federally recognized tribes. In 2020, President Joe Biden won Arizona by just 10,457 votes. That year, Democrats garnered 10,657 more votes from inside Native American reservations than they had in 2016.

Now, as a presidential election draws near, Cázares-Kelly is working to ensure that every eligible resident has a chance to cast their ballot.

At one of the last homes she approached that day, an older woman named Ann Gail opened the front gate to chat, her eyes shielded by dark sunglasses. She said she stopped believing in mail-in ballots after the fake narrative of a stolen election pushed by former President Donald Trump and his Republican allies took hold in 2020. When it comes to her own ballot, she said, “I feel like it needs to be counted and I need to see it.”

Cázares-Kelly tried to reassure her. “Vote by mail is very safe,” she said. “But I absolutely respect your decision to vote on Election Day.”

“As an elected official, and as a candidate, we need people to trust in the system and to recognize it’s non-partisan,” Cázares-Kelly continued. “Today I’m here on a partisan basis, but when I’m working, it is not partisan. It is about everybody voting.”

Gail assured her that she’ll be voting and will “get everybody in my neighborhood to vote, too,” she said. “It’s so important. My grandson turns 18 in July, and I’ve told him, ‘You have to vote.’”

Cázares-Kelly jokes that she got into voting rights work by accident. In 2016, she was an academic adviser at the Tohono O’odham Community College when her friend and colleague Daniel Sestiaga, a member of the Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe, approached her about a favor. He had been recruited by the American Indian Higher Education Consortium, which represents the interests of tribal colleges across the country, to register students to vote. He asked Cázares-Kelly if she could help. She knew all the students by name and was “just like a changemaker on campus,” he said.

On the first registration day, Sestiaga got pulled into a meeting, so Cázares-Kelly had to do the work by herself. Despite not having any training, she thought, “It’s probably not that hard. I’ve registered myself and other people. Like, it’ll be fine.”

Instead, she recalled, “It turned out to be really hard.”

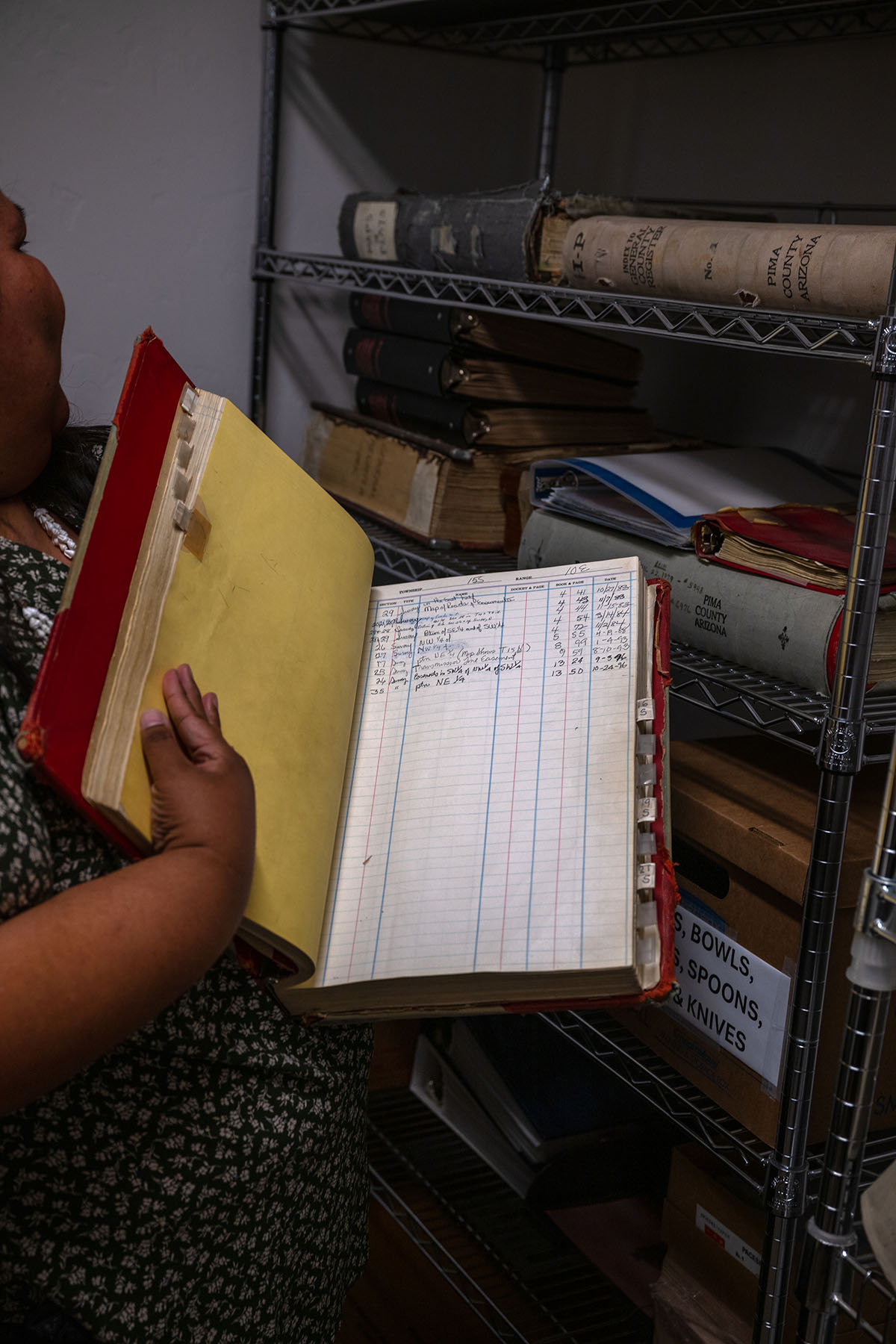

One of the challenges is that voter registration isn’t set up for the realities of tribal land. “The problem on the reservation is if you’re asked for your physical address, you just kind of make it up,” she said. “Because there is nothing you can really reference.” Instead of a street name, one might describe where they live in relation to a landmark or a mile marker. For example, the college’s address was Highway 86, milepost 125-and-a-half, she said.

The form also includes a spot to draw where you live. “Well, my nation is the size of Connecticut,” Cázares-Kelly said. “Are you asking for the shape of my nation and a star? Like, what are you looking for here?”

All of this can create confusion for residents who sometimes just list their PO boxes, which don’t count as physical addresses. That will delay their registration, Cázares-Kelly said.

Non-native students had issues, too, particularly if they were from out of state. Some students didn’t have driver’s licenses. “Every single person’s situation was so completely different,” she said. “It ended up being incredibly complex.”

She took her questions to the office of then-recorder F. Ann Rodriguez. She had so many that, at one point, she bumped her sister’s number off her speed dial list and replaced it with the number for Rodriguez’s office.

And the work was just beginning. “People started getting the voter registration cards back, getting their voter IDs in the mail, and they were so excited to show me or thank me for helping them register,” she said. But then it became, “My mom wants to register now, my auntie, my boyfriend, my uncle. How do I get them a form?” Cázares-Kelly realized she didn’t know. “It was like I pulled a thread from a sweater and all of a sudden this sweater started unraveling.”

One of the things she learned is that the post office on the reservation should have voter registration forms available, but hadn’t stocked them in years. “Having no influence and no title and no anything, I reached out to the postmaster, I reached out to the recorder’s office, and I connected the two,” she said. Soon, the forms were where they should have been all along.

Cázares-Kelly’s voting advocacy quickly turned into an obsession, Sestiaga said. One day, he recalled, “We were cruising through the village on a lunch break or something and she said, ‘If there was a way that I could make a full-time job out of getting people registered to vote, I would do it.’” Teasing her, he told her she’d just have to become the next county recorder. “She was like, ‘Get out of here! Like, I have no interest in politics. I have no interest in campaigning.’”

But she also recognized there was a need for better outreach, particularly on the Nation, he said. So when Rodriguez announced in 2019 that she was going to retire after 28 years of service, it felt a little bit like fate to Sestiago. A lot of other people who knew Cázares-Kelly had a feeling she would go for the seat. “I remember seeing that headline, and I just thought to myself, ‘Oh my goodness, she’s going to run for this,’” her husband, Ryan Kelly, said.

Cázares-Kelly wasn’t sold yet. She was, first and foremost, an educator. She had no desire to be a politician, and the thought of raising campaign money made her uncomfortable.

But it nagged at her how long it had taken to build a relationship with the current recorder’s office. She thought about having to do that all over again once Rodriguez left office. And what if the new recorder was anti-Native? “I was worried,” she said. “Eventually, I recognized that I care about this office and I understand a lot about the needs that are not being met, and I have a sense of duty to at least try.”

She launched her campaign in 2020, right at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. That meant having to canvass neighborhoods with social distancing measures in place, doing no-contact lit drops and outreach through Zoom forums and virtual fundraisers.

Worse, a candidate who wanted to win her community would need to do a lot of driving — and her car was having engine problems. She needed money to get back on the road. When she was registering voters, she sold banana bread to pay for gas. But fixing the car would take a much bigger sum, and she felt bad asking for money from people who might not have any to spare. A friend assuaged her guilt: “I think you’re saying, ‘Hey, community, I’ve invested in you,’” she recalls him telling her. “Now you’re asking, ‘Can you invest in me?’”

She set up a GoFundMe for $3,500 and quickly met the goal. “It was just shocking to me that people would give me money,” she said. But it didn’t surprise her husband, a former teacher who is now a labor organizer with the AFL-CIO. Because she never wanted to get into politics, she had won community support just by being herself, he said. “Gabby walked into the race already having so many meaningful community relationships,” he said.

Those ties had deepened in 2017, when she, her longtime friend April Ignacio and a few others co-founded an advocacy organization called Indivisible Tohono. They have organized everything from sock drives to candidate forums to Pride events on the Nation.

That network of friends was ready to spread the word about her campaign. It helped that she made a TikTok video that went viral, showing her speeding by the National Mall in Washington, D.C. on an electric scooter while wearing a traditional red dress and yelling, “Excuse me, I’m Indigenous, coming through!” That moment became part of her campaign slogan and bumper sticker design.

So when Election Day came, her supporters were hopeful that she might have a shot. “We had a good group of people who are really all rooted in the community,” her husband said. “I think we quietly suspected that it was going to be a landslide victory.”

And they were right. She beat her opponent by more than 80,000 votes.

Ignacio said it was a barrier-breaking moment for Cázares-Kelly. “As a rez girl growing up, we didn’t have the idea that we could do this. We didn’t have people in our community who were doing things like this,” she recalled. “For me to watch my best friend make history, it’s still very emotional. And I think that she’s the star who she’s always been.”

Cázares-Kelly followed the canvassing in Three Points with a Juneteenth event in Tucson, where she gave the land acknowledgment at the opening ceremony, recognizing tribes like her own that have stewarded the land. Then she stayed to mingle with the crowd. As she strolled by the booths — some selling lemonade, others representing the gun reform group Moms Demand Action and the African American Democratic Caucus — people stopped her to shake her hand and fangirl about meeting her.

She’s something of a local celebrity, which she didn’t expect as an elected official doing an administrative job. When she ran, “it wasn’t a sexy position,” she said. “Most people didn’t care about the recorder’s office.”

Two things contributed to her popularity. One is that Cázares-Kelly, despite her initial shyness, is charismatic and funny and beloved by Pima County voters, who cast more votes for her than any other Democratic countywide candidate in the July primary. The other, a more somber reality, is that the 2020 election raised the profile of county recorders after the Trump administration spread unfounded conspiracy theories that votes in Arizona weren’t being counted.

That fundamentally changed how she had to run her office. She immediately created a communications team to counter disinformation and teach people how voting works. In May, they invited a small group of community members and journalists into a highly restricted part of the office to see how ballots are counted. She also recently hosted a series with the Pima County Interfaith Council, visiting five churches to talk about a “day in the life” of the ballot. She draws inspiration from educational programs like “Mr. Rogers” and the “How It’s Made” videos about crayons or peanut butter. “I think people just want to know those types of things,” she said.

She also uses social media to spread information about voting, tailoring the messages to the medium. Twitter is for journalists and other “nerds,” as she put it, so she tends to be wonkier there. Facebook and Instagram are for people like her sister, who don’t really care about the granularity of politics, but might be enticed if she can explain what her office does.

“I think people have for a really long time been very dismissive of social media,” she said. “But we can very much see a parallel between what happens on Twitter and Instagram and what happens in person.” For example, she said, when Kari Lake, a far-right Republican who ran for governor in 2022 and is now running for the U.S. Senate, sent out a tweet suggesting ballot counting was being slow-rolled to prevent her from winning, “it results in physical phone calls to my office.”

Voter outreach will matter a lot this year, in what former recorder F. Ann Rodriguez describes as a “big election” for both the county and the nation. She points out that Pima is Arizona’s second most-populated county, after Maricopa, which happens to be one of the fastest-growing counties in the United States. And several hot-button issues will bring out voters: This year both abortion rights and the wages of restaurant workers are on the Arizona ballot.

For now, a lot of Cázares-Kelly’s work happens at events like this one, where she can answer questions in person. At the booth for NextGen America, which focuses on getting out the youth vote, she chatted about how the work was going and offered a pro tip learned from years of dealing with registration hassles: Instead of asking if someone is registered to vote, ask if they are registered at their current address. (Sometimes people move without updating it.)

Two booths down, at the Saavi Services for the Blind tent, she talked to Mohammed Falah about a tool called a ballot marking device — a machine that helps people with disabilities vote. It can read a ballot to a person through headphones, offers functions for large print or color contrast and has a controller that people with hand mobility issues can use to select their voting option. She said her office would be happy to demonstrate it for his organization.

The county had the machines before she came into office, but, she said, much of the staff didn’t know how to use them. “They were like a nice decorative thing on the side of the room and if somebody asked to use it, [staff] would have to take out the instruction booklet and troubleshoot,” she said. “Then that person’s having to wait. And often it would lead to people feeling discouraged and embarrassed. And, you know, they may choose not to participate.”

Listening to what the community needs, Cázares-Kelly said, “makes it better for everybody.” Sometimes it’s as simple as having a table with chairs at early voting locations. Older people started requesting that accommodation, she said, “but then we would see people who come in with a boot on their foot.” Once, she watched a mom sit down to breastfeed her child while voting.

Her office has taken other accessibility measures, like making sure that PDF documents are compatible with a screen reader, a tool that can read text aloud or translate it into Braille. All of her social media communications include an image description for the same reason.

As of 2016, there were about 175,600 visually impaired people in Arizona, and the population is aging, Falah said. This means more people will soon need these accommodations. “We are a retirement state,” he said. “If we do not tackle it now, then when?”

A few weeks later, Cázares-Kelly was standing in front of a class of soon-to-be graduates from a training program that helps Indigenous people overcome the unique challenges they’ll face while running for office. Native politicians are often some of the first from their communities to either run or hold their positions and that usually comes with a fair amount of pushback or skepticism.

Cázares-Kelly opened her talk by greeting the students in the Tohono O’odham language. Switching back to English, she said, “You are on O’odham land.” Then she added, with a smirk, “So — you’re welcome.” The group burst into laughter. It felt like a cheeky inside joke for a group of people who’ve likely been asked to do land acknowledgements for non-Native audiences. But the lighthearted moment quickly turned serious as Cázares-Kelly launched into the story of how she became involved in voting rights work thanks to her earliest influence, her grandmother.

Cázares-Kelly grew up in two different communities in the Tohono O’odham Nation. One is called Kupk, a remote place where she spent her summers. The rest of the year, she lived in the village of Pisin’ Mo’o, which had some services, like a bus stop. She lived next door to her grandmother, Catherine Josemaria. Cázares-Kelly refers to her affectionately as her Hu’uli-bat, which is O’odham for “my dearly departed mother’s mother.”

They would communicate across their two languages, her grandmother in her broken English and Cázares-Kelly in her broken O’odham. They were always together, she said. Her grandmother showed her how to harvest traditional foods and she recalls watching her grind corn and clean tepary beans in the kitchen.

But she also remembers another tradition: her grandmother’s voting ritual. It was a right Josemaria did not have until she was 30 years old. She was born in 1918 and granted citizenship six years later, but it wasn’t until 1948 that Native Americans won the right to vote. Even then, for decades, voting barriers like literacy tests specifically disenfranchised non-White and Indigenous people.

But that didn’t stop Josemaria from being politically active. “She was a brilliant woman and she was a community leader,” Cázares-Kelly told the group. “We had visitors every single day of my youth, people wanting to hear her stories and her gossip — she was the gossip queen — and get her advice and have political discussions with her.”

On election days, Cázares-Kelly would comb and braid her grandmother’s long gray hair and pin it up in a bun. Her grandmother would don a dress and a little purse, and Cázares-Kelly would help her into the passenger seat of her car. Cázares-Kelly was too young to legally drive, but it was pretty common to start driving young on the reservation — and extremely important to get her grandmother to the polls. It only occurred to her later that what her grandmother was doing was a big deal, an act of defiance. “She would not have had the full freedom of having a language translator until the mid 1970s, which isn’t that long ago,” she said.

Once they returned home, her grandmother would go to her bedroom and tack her “I voted” sticker on the vinyl faux wood wall next to other stickers she had collected over the years. The oldest ones, Cázares-Kelly remembers, were yellow and worn.

The importance of those stickers stayed with her. They serve as reminders to vote and are a source of pride. It’s part of the reason why in 2022, Cázares-Kelly’s office released new stickers for early voters with the words “I voted” written in English, Spanish and O’odham, one on top of the other.

Her office has also expanded the role of the Tohono O’odham outreach coordinator to spend more time in the field talking to tribal residents and made it a priority to reinstate an early voting site for the Pascua Yaqui Tribe. The tribe had sued the previous county recorder after she closed the site in 2018 just a few weeks before an election. (A judge sided with the decision to close the site, saying there wasn’t evidence that closing it made it harder to vote.)

Sestiaga recently told Cázares-Kelly how crucial that voting center has been for him. Even though he’s not a member of that tribe, voting at a site where people look like him makes him feel safer. He used to vote at a church in a predominantly White neighborhood and “going in as the young, Brown-skinned, darkest person in the room, I got looked at. I felt like people were watching me, like I was getting judged.”

Sestiaga is able to vote at that site due to a change the county government made in 2022: Instead of having to go to a specific precinct, a resident can vote at any center in the county. Eleven other Arizona counties use this model and its popularity is spreading. According to the Voting Rights Lab, an advocacy organization, voter centers are more convenient, widely popular and could increase turnout.

The centers also make voting easier for people on the reservation. As with any rural area, if someone shows up at the wrong precinct, it can be a long drive to the right one. And not everyone can afford that kind of error, said Cázares-Kelly. Many people don’t have cars or can’t afford to spend extra money on gas. Public transportation systems aren’t reliable, if they exist at all.

As she wound down her speech at the leadership conference, Cázares-Kelly reminded the students that running for office is about advocating for their communities — not just when it comes to voting rights, but other policy decisions that are shaped by elected officials, like in health care or infrastructure.

“It’s our duty to protect our community,” she told them. “And if that means that we’re not doing it in the traditional way, but we’re having to learn the language of government and policy and funding to protect our people, then it’s our duty to at least try.”

A few weeks after she announced she would run for president, Kamala Harris held a rally in Glendale, Arizona, a sprawling suburb just outside Phoenix. As she watched one of the opening speakers, the governor of the Gila Indian River Community, come up to the stage, Cázares-Kelly exclaimed, “There’s hella Natives up in this piece!”

Harris and vice presidential nominee Tim Walz talked about some of the most pressing issues in Arizona: immigration and abortion restrictions. Harris also promised to pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would strengthen protections against discriminatory voting practices.

Cázares-Kelly was happy to hear it. But on the drive back home, she said that some of the things she heard at the rally didn’t resonate with her, like when Arizona Sen. Mark Kelly talked about the “army” Democrats need to win the next election. Her tribe, whose ancestral lands straddle both sides of the border, is heavily surveilled by the border patrol, which has a history of harassing and even deporting tribal members. The military rhetoric, she said, “doesn’t make me feel safe.”

Though she is a registered Democrat and a delegate at the Democratic National Convention, she stands to the left of the Harris-Walz ticket and has felt conflicted by its more moderate stances. Also, as an Indigenous person, her identity is inherently political. One of her idols, Minnesota Lieutenant Governor Peggy Flanagan, a citizen of White Earth Band of Ojibwe, once put it this way: These political systems were not designed to include people like her, but to eradicate and assimilate Indigenous people.

“So we’re still fighting the structure of white supremacy and anti-Indigenous sentiment and all of these other issues,” Cázares-Kelly said, “and we’re having to change the culture about what our role is in that.”

Eventually, the conversation turned to her own political future. Already, people have been speculating about whether she’d consider a higher office, but she promised herself she’d stay in the role for at least two terms. “I don’t know how I’ll feel in another four years, but four years has flown by for me,” she said.

It was past 10 p.m. and she was still making her way home. But the long day hadn’t sapped the energy in her voice or her enthusiasm for the job.

“There is so much work to do,” she said.

To check your voter registration status or to get more information about registering to vote, text 19thnews to 26797.